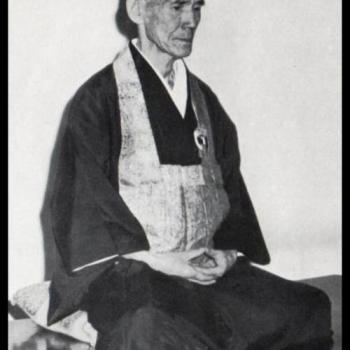

Sudden, great awakening is the life blood of the Zen school, both Soto and Rinzai. In this post, I’ll share one such great awakening – that of the important Soto ancestor, Keizan Jokin Zenji (1264-1325) – and make a few comments. May awakening stories like this one inspire your process to awaken fully and live congruently as such.

Keizan is up for me these days because Tetsugan Sensei and I are working through the last eight chapters of his Denkoroku (The Record of the Transmission of Illumination) with our Vine of Obstacles Zen group of training students. This includes the last six generations in China and the first two in Japan. We also use the Denkoroku in advanced koan study, as is typical in the Harada-Yasutani line, but it is such a powerful and beautiful text, that we wanted to share it with all of our students now.

Click here to read an ad-free version of this post and to support my Zen teaching practice at Patreon, including translations and writings like this.

I’ve previously posted about Keizan, of course, including Keizan’s “Answers to Ten Questions from the Emperor,” comprised mostly of a translation by Kokyo Henkel Osho, the current tanto (head of practice) at Green Dragon Temple (aka, Green Gulch Farm). That post also includes a slightly different telling of Keizan’s awakening as well as his instructions for working with the mu koan.

In this post, too, I’ll use translation by Kokyo, this one from Tojo Shoso Denki Shusei (Dongshan Lineage Various Ancestors Transmission Record Collected Works). Here’s the story:

“One morning Tetsu Gikai went up in the Dharma Hall and raised the case of ‘Ordinary mind is the Way.’

Keizan suddenly realized great awakening and said ‘I got it.’

Gikai asked, ‘What have you realized?’

Keizan said, ‘A black lacquer person runs through the night.’

Gikai said, ‘That’s not yet it, say more.’

Keizan said, ‘At tea-time, I drink tea; at meal-time, I eat rice.’

Gikai smiled and said, ‘This person in the future will arouse the ancestral wind.’”

Zen stories that end with a smile are the best!

In this case, it’s the “he did get it” smile of Tetsu Gikai. For more about this important ancestor, see “Seven Stumbles, Eight Blunders: The Life of Tetsu Gikai.”

In this version of Keizan’s awakening, old Gikai gave a dharma talk on a koan that also has been very important for many Zen students, including me. It occurs in The No Gate Barrier, case 19, and goes like this:

“Zhàozhōu asked Nanquan, ‘What is the Way?’ Quan said, ‘Ordinary mind is the Way.’ Zhou asked, ‘Is it possible to direct oneself towards it then?’ Quan said, ‘To intentionally try to do that is scheming.’ Zhou asked, ‘If not intentionally trying, how can you know the Way?’ Quan said, ‘The Way does not belong to knowing or not knowing. Knowing is delusion, not knowing is blankness. If you truly reach the Way of no intention, it’s like the great empty universe, a vast open thusness. How could you make an effort of right and wrong?’ At these words Zhou had a realization.”

Zen stories about an awakening to ordinary mind are the best!

In Zen, you see, “ordinary” is ordinary and it is “the great empty universe, a vast open thusness.” Thusness might not seem ordinary, but that notion that there’s a difference is delusion. The collapse of the distinctions of thusness and the ordinary is awakening.

It is also notable that two of the most common times for people to openly accord with awakening are in interactions with their teachers (like in Zhaozhou’s case) and during dharma talks (as in Keizan’s case). In this one post, we cover ’em both. So you’ve got that going for you too.

Now back to our main focus – Keizan’s awakening. After he hit on it, Keizan reported to Gikai, “I’ve got it!” That kind of confidence is also common. When you see it, you know you’ve seen it – and that confidence should encourage one to show it to their teachers, for starters. If it doesn’t encourage the process of verification within relationship, then it’s probably more delusion than awakening.

Gikai asked Keizan what he had realized and Keizan said something unusual: “A black lacquer person runs through the night.”

In his research into the “black lacquer person” (kunlun, 崑崙), Kokyo found that the ancient Chinese were familiar with people with black skin, possibly from Africa and also the islands in the Indian Ocean, and considered them exotic and to have occult powers. Black skin, at least sometimes, also had a negative connotation and although caution is needed not to just project present bias back in time, there may have been what we’d now call racism (or xenophobia) involved.

In Keizan’s use of the term, though, the significance is transmuted into the paragon of awakened action – a black, nondual person acting freely in the dark night. It’s like a person reaching back in the night for a pillow.

Zen stories about an awakening that flip contemporary prejudices on their butts are the best!

Gikai, though, pushes Keizan further with “That’s not yet it, say more.” Keizan responded, “At tea-time, I drink tea; at meal-time, I eat rice.”

A clear expression of the second rank, true within the biased.

But don’t worry about which expression is what – it really isn’t much about the words. Keizan’s whole-body presentation is what Gikai would be attending to when pushing or verifying him.

And with that, Gikai smiled and verified Keizan, “This person in the future will arouse the ancestral wind.”

This verification also included encouragement – “in the future” – for Keizan to continue on the Way. I hear Gikai here saying, “You’ve got a good clear taste, and now the work is to continue deepening and actualizing this awakening timelessly.”

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with Vine of Obstacles Zen, an online training group. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, was published in 2021 (Shambhala). His third book, Going Through the Mystery’s One Hundred Questions, is now available. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi.