(LDS Media Library)

I return, yet again, to BYU Studies Quarterly 61/4 (2022), which is a special issue of the regular quarterly publication BYU Studies. It was created by four faithful Latter-day Saint Egyptologists — Stephen O. Smoot (Ph.D. candidate, Catholic University of America), John Gee (Ph.D., Yale University), Kerry Muhlestein (Ph.D., University of California at Los Angeles), and John S. Thompson (Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania) — and bears its own unique title: A Guide to the Book of Abraham. As I’ve previously indicated, it represents something of a state-of-the-question survey from people who are thoroughly familiar with the topic and the issues. I’ve tried to state as clearly as I’m capable of stating it that I am largely quoting bottom-line conclusions. I am not claiming to reproduce the evidence and the arguments on which those bottom-line conclusions are based. For such evidence and arguments you should consult A Guide to the Book of Abraham itself.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

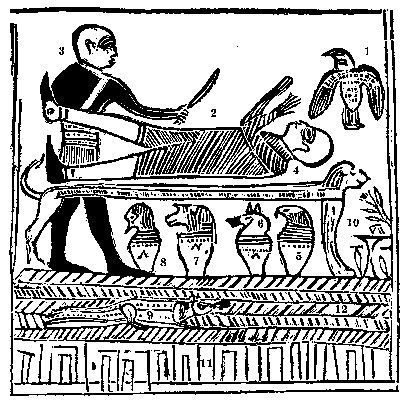

In a short section titled “Approaching the Facsimiles” (209-214), the authors first lay out a number of contrasting paradigms for understanding the Book of Abraham facsimiles and their relationship (or lack thereof) to the Book of Abraham itself. They note the all of them have strengths, but that none by itself seems to account for all the data.

Whichever paradigm one adopts, it seems clear that Joseph Smith’s explanations of the facsimiles were original to himself (none of the explanation appear next to the illustrations on the papyri he possessed). “There are aspects of [these explanations] that match what Egyptologists say they mean. Some [of them] are quite compelling. . . . However, as we look at the entirety of any of the facsimiles, an Egyptological interpretation does not match what Joseph Smith said about them.” This is complicated by the fact that even though not all of Joseph Smith’s explanations of the facsimiles in their entirety agree with how modern Egyptologists understand these illustrations, in many instances they do accurately reflect Egyptian and Semitic concepts. (211-212, quoting Professor Kerry Muhlestein)

There is a fundamental problem in choosing between such paradigms or, thus far, in choosing to create an altogether new one:

Despite some important advances in scholarship, “we [still] do not [entirely] know to what we really should compare the facsimiles.” For instance, we must ask if Joseph Smith meant to give us “an interpretation [of the facsimiles] that ancient Egyptians would have held, or one that only a small group of priests interested in Abraham would have held, or something another group altogether would have held.” Or, alternatively, “was he giving us an interpretation we needed to receive for our spiritual benefit regardless of how any ancient groups would have seen these?” The fact is that we don’t know for sure. While we “can make a pretty good case for the idea that some Egyptians could have viewed Facsimile 1 the way Joseph Smith presents it, [we are still] not sure that is the methodology we should be employing. We just don’t enough about what Joseph Smith was doing to be sure about any possible comparisons or lack thereof.” (213)

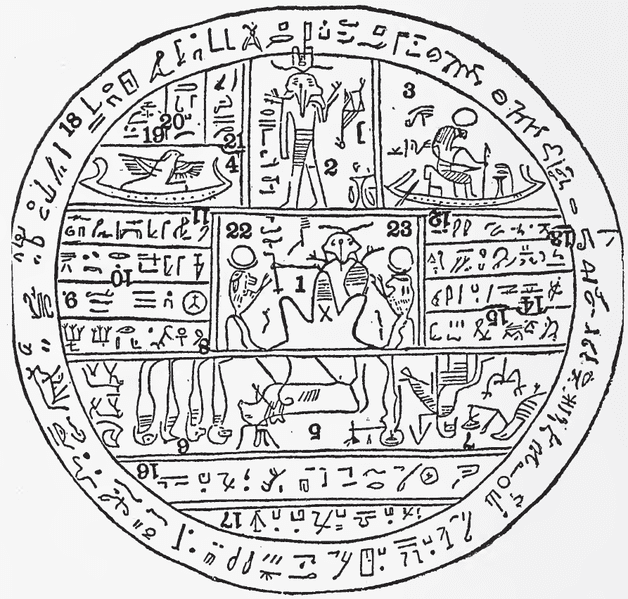

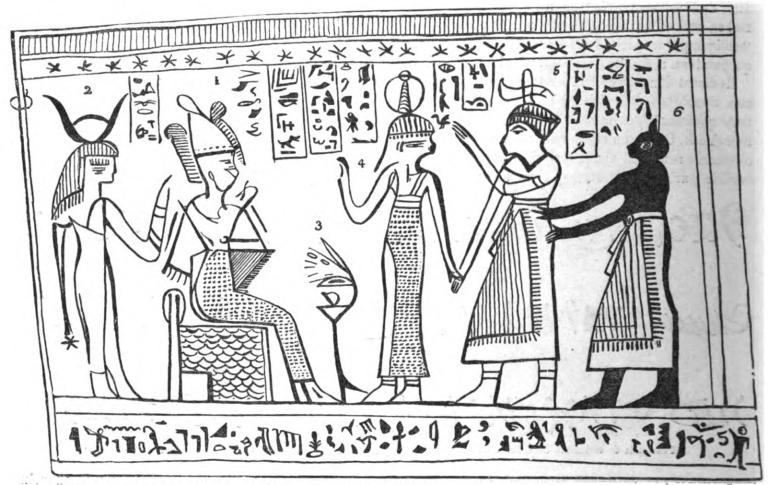

Turning specifically to the third of the three Book of Abraham facsimiles, the authors write that

“Facsimile 3 has always been the most neglected of the three facsimiles in the Book of Abraham. Unfortunately, most of what has been said about this facsimile is seriously wanting at best and highly erroneous at worst.” Some valuable work in recent years . . . has helped . . . better situating this facsimile [Facsimile ] in its ancient Egyptian context. As that context has become clearer, elements of Joseph Smith’s explanations have become more plausible (although other elements remain at odds with current Egyptological theories). (214, quoting Professor John Gee)

And, finally, here is a very important point. I’ve italicized the last sentence in order to ensure that it isn’t overlooked:

Whichever theoretical paradigm one adopts in approaching the facsimiles, a respectable case can be made that with a number of his explanations Joseph Smith accurately captured ancient Egyptian concepts (and even scored a few bull’s-eyes with his explanations) that would have otherwise been beyond his natural ability to know. Any honest approach to the facsimiles must recognize this and take this into account. (213)

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image )

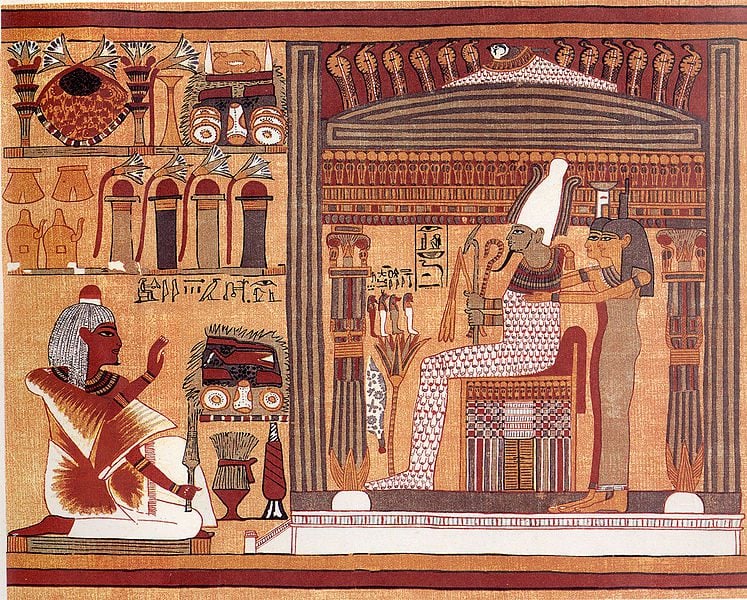

The immediately next section of the volume is “A Semitic View of the Facsimiles” (215-220), which is, to a substantial degree, devoted to sympathetic consideration of Kevin L. Barney’s important article “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2005): 107-130. An important aspect of Barney’s article is its treatment the judgment scene in the apocryphal Testament of Abraham, which seems to draw quite directly from the judgment imagery in chapter 125 of the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Barney argues that “studying only the Egyptian context of the facsimiles will never yield a complete explanation of the significance of Joseph’s interpretations. We need to be able to look at them the way [a hypothetical ancient Jewish redactor] did, as Semitized illustrations of the Book of Abraham. When we see them from this perspective, our vision gains clarity, and the facsimiles and Joseph’s interpretations come into focus.” (218-219, quoting Kevin Barney)

In conclusion to this section, the authors remark that

Ultimately, there is still much to discuss and consider when it comes to the interpretation of the facsimiles of the Book of Abraham. Barney’s theory, while perhaps not definitive, is “valuable and attractive” and offers important “new avenues for further research.” It also provides one way to understand Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the facsimiles in a plausible ancient light. (219, quoting Kerry Muhlestein)

Happily, the present volume’s discussion of specific details of the Book of Abraham facsimiles continues for almost a hundred further pages — which will be covered here in due course.