While in California a couple of weeks ago, I picked up a copy of Gerard Verschuuren, A Catholic Scientist Harmonizes Science and Faith (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2022). Dr. Verschuuren studied human genetics and the philosophy of science at Leiden University, the University of Utrecht, and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, all in The Netherlands, and now — since 1994 — lives and writes in the southern part of New Hampshire.

I found the very first lines of his book interesting. That’s why I decided to buy it. He commences as follows:

The idea that science and faith can live together is an issue of vital importance for people of faith. Yet, more and more people nowadays claim science and faith cannot really live together. They caricature religious believers as “schizophrenics.” On weekdays, they are critical, want proofs, look for arguments, and believe something only if there is no further doubt. Then, on Sundays, they turn a switch, set their understanding to zero and their gaze on infinity; they have no need for proofs, they open their mouths and swallow revealed truths and absurd dogmas.

The contrast painted in this parody is clear: religious believers live a “schizophrenic” life. It is the life of science and reason on weekdays and the life of religion and faith on Sundays. Of course, it is a travesty, but a very widely held one nowadays, heavily promoted by media and academia. Let’s see why it is a false contrast. (3)

Dr. Verschuuren has much to say over the next several pages about what he plainly regards as a false contrast, indeed as a “caricature” and a “travesty.” I agree with him on that assessment, but I rather liked his immediate response over the next page or two. He makes a fairly simple and probably obvious point, but he makes it well.

He simply points out that the dividing line between the realm of weekday living and that of religious faith is not nearly as clear and stark as the caricature suggests.’

For one thing, he says, we cannot and we typically are not asked to accept on faith something we absolutely cannot understand. So reason must be employed in order to make at least minimal sense of the propositions that are delivered to us by religious faith.

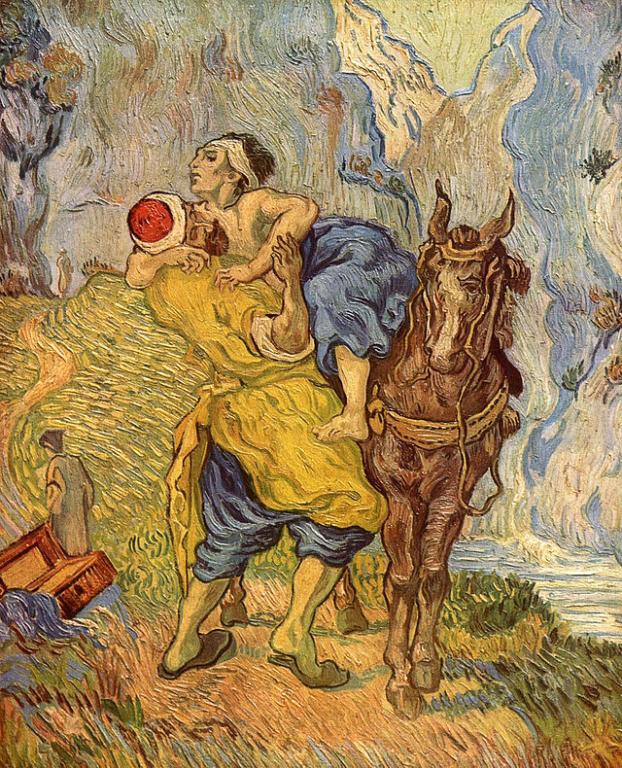

I offer some examples of my own that, I think, illustrate Dr. Verschuuren’s point and with which he would be content: What does it mean to speak of God? What does it mean to affirm that Jesus was divine, or that he in some ways came to save us? To what do his miracles — the apostle John calls them “signs” — point? And there are, surely scores if not hundreds or thousands of other declarations of faith where, to be affirmed, they must be at least somewhat understood.)

I also note, although he himself has not yet done so in my reading of him, that there are scientific propositions that we are invited to affirm that we — certainly I — do not wholly or even minimally understand or cannot comprehend: Is light both wave and particle? Is space curved? Are there multiple dimensions beyond the four with which we’re familiar? What about the singularity at the time just prior to the Big Bang? What does it mean for time to have come into existence at some point 13.8 billion years ago? What was there prior to that? Nothing? How can I even imagine such a thing? And yet current science seems to require that I affirm such things, even if I can’t even pretend to understand them.

“Reason itself depends on faith to begin with,” writes Verschuuren, “faith in our senses, faith in our intellect, faith in our memories, and faith in what others have discovered” (4).

Again, I offer some examples: We take it for granted that the deliverances of our senses of touch, smell, hearing, sight, and taste, while they are not infallible and may need occasional correction, provide us with a reasonably accurate picture of the “real world” around us. If we rejected such confidence in our senses, science would be completely impossible. If, moreover, we denied that our intellectual processes, our reasoning, is reliable, we would have no reason to trust any argument or demonstration that any scientist had ever made or, for that matter, that we ourselves had ever made. (This is a point that C. S. Lewis often made — and he made it, to my judgment, to great effect. Even Charles Darwin occasionally wondered whether a simian brain that had evolved in order to facilitate survival and reproduction on the African savannah should really be trusted to do science.) And, finally, if the past were totally beyond recovery, and if, thus, our recollections of the past were competely worthless, neither science nor historiography nor even ordinary daily life would be feasible.

Dr. Verschuuren’s point, accordingly, is that science and scientific reason are not free of faith, and religious affirmations are not totally divorced from reason. Thus, the caricature that attempts to portray religion as wholly irrational and purely faith-based, as contrasted with a science that has absolutely no need of faith but, rather, is firmly based in objective reason, can’t withstand scrutiny: “This means that “weekdays” and “Sundays” cannot be disconnected from each other, as the caricature suggests” (4).

Moreover — and here is another important point that demands further elaboration — “Faith can cover issues that science and rationality are inherently incapable of addressing, but that doesn’t make them unreasonable or unreal” (4). (See the photograph above.)

Following the First Presidency’s recent announcement that a medical school is to be established at Brigham Young University, there were expressions of surprise and satisfaction as well as, in some circles, of doubt and even derision. I alluded just a bit to the doubt (and to the derisive mockery) in a recent blog entry. (See “The Church in Recent Media.”) Now there is a thoughtful piece on the topic from the estimable Tad Walch, of the Deseret News: “BYU’s medical school will be rare: How many faith-based schools are there? How religious are they? Leaders of other faith-based medical schools share how they employ faith to help train excellent, compassionate doctors.”