- Trending:

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Beliefs

Sacred Narratives

Sacred narratives play a major role in Mormon thought. At the most basic level, Mormonism shares with other Jewish and Christian groups the sacred stories of the Hebrew scriptures, including the creation of the earth by God, the creation of Adam and Eve and their life in and expulsion from the Garden of Eden, and the story of Noah's flood.

Mormons take a slightly different approach to some of these stories than many other traditions, however. For example, in the Mormon version of the sacred creation narrative, Jesus Christ, who before his birth was the Jehovah of the Hebrew Bible, created the earth and all things on it at the direction of God the Father. Jehovah was assisted in this by other "noble and great" spirits, most notably the angel Michael. Michael, according to the Mormon narrative, was born on earth as Adam, the first mortal man.

The story of the fall of humankind, Adam and Eve's sin, is also somewhat different within Mormonism. Rather than a tragic event that had to be rectified, Mormons believe that the fall was always part of God's plan and that it was necessary in order for humans to procreate and to undergo the necessary mortal experiences that would allow them to return to the presence of God.

Mormons share with other Christians the sacred narrative of Christ's life as presented in the New Testament. Mormons tend to be conservative in their reading of scripture, and tend toward an acceptance of the stories of Jesus' life, teaching, death, and resurrection as historical truth. In this, they remain quite close to conservative Christian groups in their reading of these narratives.

Mormons differ, however, in their use of extra-biblical literature. The Book of Moses and The Book of Abraham, which are published as part of a collection of sacred texts called The Pearl of Great Price, elaborate on the biblical themes of creation. The Book of Moses recounts the creation but provides a more detailed account of events such as the Noachian flood and the events surrounding Enoch's City of Zion. In the Book of Abraham, which Smith said he translated from some ancient Egyptian papyrus fragments, the sacred narrative is taken back in time to a period in which the spirit children of God helped to create the earth, and participated in a "war" that pitted the followers of Lucifer against the followers of Jesus.

The Doctrine and Covenants, a collection of divine revelations to Joseph Smith, contributes to the shaping of Mormon sacred narrative by adding a distinctly American flavor to the biblical narratives. This is particularly true of revelations that identify an area in Missouri as the place where Adam and Eve found themselves after being cast out of the Garden of Eden.

Chief among the extra-biblical sources used by Mormons to create sacred narrative is The Book of Mormon, which claims to be a record recounting the migration of several groups from Jerusalem to the Americas in antiquity, and the history of those groups as they unfolded from the time of their various arrivals until the last of these civilizations was destroyed in the 5th century C.E. The bulk of the record concerns the history of Lehi, a prophet from Jerusalem who, at the command of God, took his quarreling family and fled into the wilderness around the year 600 B.C.E.

Lehi sailed to the Americas where his family split into warring factions named after two of Lehi's sons, Nephi and Laman. The story traces the rise and fall of these civilizations, and emphasizes the evils of pride and the corresponding turn from God's true faith that such an attitude always precipitates. The Nephites, who had been the most righteous branch of Lehi's posterity, eventually succumbed to pride and sin and were vanquished and destroyed by the wild and ferocious Lamanites. These Lamanites, according to the Mormon narrative, are among the ancestors of the Native American tribes. Modern Mormon discourse draws heavily on these motifs from the narrative of The Book of Mormon, especially the oscillating process of repentance, humility, divine blessings, increased hubris, and sin that Mormons refer to as the "pride cycle."

Beyond the scriptural canon, Mormons in their temple worship employ yet another type of sacred narrative. Mormon temples are open only to members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS) who pass stringent tests of orthodox belief and practice. One ritual performed in the temples is called the "endowment," during which initiates are taken on a symbolic journey. Participants watch as a sacred narrative unfolds that recounts the creation of the earth, the events in the Garden of Eden, and the interaction of Adam and Eve with heavenly messengers who teach them the gospel of Jesus Christ. Initiates then participate in the symbolic entrance into the presence of God, using the knowledge presented by the angels to Adam and Eve.

A final element of Mormon sacred narrative makes use of what may be termed the pioneer epic. The story of early Mormonism is one of frequent persecution and hostility. Modern Mormons, even those outside of the United States, feel a deep sense of attachment to the sacred story of suffering and eventual triumph that follows the Mormons from their early defeats in Missouri and Illinois, their arduous and deadly trek across the Great Plains, and their settlement and prosperity in the remote American West. As with all sacred narrative, the Mormon pioneer epic is often used to contextualize and give perspective to the problems and difficulties of the present by recounting the travails and glories of the past.

- Why do 'Mormons' serve missions?

- What is the LDS Word of Wisdom?

- Do 'Mormons' still practice polygamy?

- Why don't 'Mormons' drink alcohol?

Ultimate Reality and Divine Beings

For Mormons, life on earth is the middle part of a drama that began long before the creation of the earth, and which will continue endlessly after death. Human beings once lived as spirit children of God. Before that, they existed as "intelligences," beings of undefined substance, that would one day be organized by God into sentient spiritual beings.

Mormonism's founder, Joseph Smith, taught that absolute creation and destruction were impossibilities, because the elemental substance at the heart of all things existed eternally, as long as God. Mormons emphasize that God organizes things into increasingly complex and potentially glorious forms, but they reject the common Christian theological concept of creation ex nihilo, or out of nothing.

One key to understanding this idea is Joseph Smith's teaching that God was once a man. Smith taught in the 1840s that the "great secret" of the universe was that "God himself was once as we are now, and is an exalted man and sits enthroned in yonder heavens." In other sermons, Smith suggested that God had at one time lived as a mortal being on an earth and, through faith and adherence to eternal laws, became exalted. God, according to the Mormon view, is a married man and inhabits a body of flesh and bone, but not of blood, a substance present only in mortal beings. This embodied God provides prophets to teach his spirit children, once they are born into a mortal body, the laws and rites that must be observed in order for them to become gods themselves. As gods, they will have the power to organize intelligences and populate worlds of their own, all with the goal of having these spirits become exalted and so on ad infinitum.

Thus, in Mormonism there exists an infinite number of possible gods, although Mormons only worship as their God the one who organized their spirits and created the earth upon which they live. Together with God the Father, Mormons also worship Jesus Christ, whom they believe to be the first spirit that the Father organized from the "intelligences," as well as the literal offspring of God the Father and the Virgin Mary. The resurrected Christ also has a body of flesh and bone.

Mormons also believe in the third member of the Godhead, the Holy Ghost. This being does not yet have a body, and his exact nature remains somewhat mysterious, although his role as a comforter and testator of truth are clearly defined. Mormons also believe that there is a Heavenly Mother, but they are discouraged from speculating about the nature of this being and Mormons may face ecclesiastical sanctions if they offer public prayer to her.

Mormons view mortal life as a time of learning and testing, as well as an opportunity to develop the godlike traits that they will need if they hope to live as a god in the next life. Marriage is seen as an ideal place for the development of those abilities and skills. Thus, the notion that God is married, coupled with the belief that human beings may become gods and goddesses through imitation of the divine, explains why marriage in Mormon temples, for time and eternity, is so central to LDS soteriology.

Mormonism has no specific category of angelic beings separate from humans, although the term is sometimes used to describe beings that were or will be human beings, and as such are best understood as spirit messengers rather than angels as the term is commonly used in other faith traditions. Beings that once lived upon earth are sometimes given special missions from God to visit, teach, and sometimes punish humans. The most famous Mormon angel is Moroni, who told Joseph Smith about the existence of the golden plates, which Smith later translated as The Book of Mormon.

- How does Mormonism understand humanity's relationship to God?

- How do Mormons view mortal life? How is this connected to marriage?

- How do Mormons understand angels?

Human Nature and the Purpose of Existence

According to The Book of Mormon prophet, Lehi, "Adam fell that man might be, and men are that they might have joy." Mormonism tends to take a positive view of the purpose of existence, with the ultimate goal of living "with God, as God." Humans are gods and goddesses in embryo, spirit children of God who have entered into mortality in order to gain a physical body, which according to Mormon theology is an integral part of divine life, and to undergo the testing of moral agency.

Mormons view life as a training ground for the work that will continue after death, where faithful souls will continue to create and populate worlds and where they will impart the keys of the knowledge of eternal life to their own spirit children. Mormons hold that "the glory of God is intelligence" and it is thus no surprise that Mormons place a strong emphasis on education, and they believe that persons will take with them to the next life all knowledge and skills that they develop during their mortal life on earth. The accumulation of knowledge is coupled in the Mormon ideal life with the mastery of physical appetites and passions that naturally flow from corporeality.

Despite the view that the physical body is a gift and that life is a place to learn, grow, and experience joy, Mormon scripture follows the broader Christian tendency to see humans as "fallen" and thus in need of profound change. In fact, The Book of Mormon calls humans "carnal, sensual, and devilish," and warns that unless the "natural man" is shed through the process of being born again, the progression of the soul will be stifled.

Part of the purpose of existence is to develop sufficient knowledge of God and humility of spirit to allow the loftier, more spiritual side of an individual to rein in the carnal elements. Mormonism thus shares with much of Christianity the view that the physical body introduces feelings and desires that may lead one away from God. However, Mormonism holds that the key to rectifying this problem is not to mortify the body, but to employ moral agency and spiritual refinement to bring the spirit into mastery of the body. Together, the body and the spirit will work together to create a being of great power. Founding Mormon prophet Joseph Smith taught that any being with a body has power over a being that lacks one. Thus the idea of carrying a body throughout eternity is a central element in Mormon thought.

Mormons hold an infinitely expansive view of human potential, and view the purpose of existence as encompassing the attainment of a physical body, accumulation of knowledge, and the mastery of divine laws, all of which work together to allow human beings to transcend their fallen and carnal state and to attain a state of godhood.

- What can be said about the relationship between education and existence?

- How is the physical body held in tension to the soul?

- Why is the story of the fall essential to Mormonism's understanding of human nature?

Suffering and the Problem of Evil

In Mormon thought, the most important moral principle is that of agency. Agency existed as a necessary element of existence even before human beings populated the earth. Drawing from and elaborating on biblical accounts, Mormon scripture tells of a "war" in heaven in which God's spirit children had to choose between two plans. The first plan was presented by God himself and endorsed by his eldest spiritual child, Jesus Christ. It held that, once born into mortality, human beings would be free to choose between good and evil. This plan recognized that some of God's children would choose evil and thus be banished eternally from God's presence. Others would choose good and, in so doing, could eventually become gods and goddesses themselves.

The second plan, designed by Lucifer, one of God's most promising and talented children, called for the suspension of moral agency. Lucifer argued that he would force all humans to choose good over evil. In return for his role in exalting and saving the totality of God's offspring, Lucifer demanded God's throne and glory. Lucifer and the one-third of God's spirit children who sided with him were cast out of God's presence and denied the opportunity to inhabit a physical body. Lucifer, who became known as Satan, and his angels actively tempt mortals to choose evil, but Satan is not the founder or source of evil.

The narrative of the war in heaven is based on the idea that evil existed before Satan. The narrative hinges on two concepts: that moral agency is an eternal principle that cannot be abrogated, even by God, and that moral agency requires a choice between, and thus the existence of, good and evil. Mortals are placed on earth in order to experience the forces of good and evil and to choose between them.

The story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden thus takes on a slightly different cast in the Mormon telling. The fall of Adam and Eve is not seen as the source of moral evil, because the presence of Satan in the Garden as a fallen and rejected angel presupposes a universe in which agency, with its attendant choices of good and evil, was already operative. In fact, the Mormon view holds that Satan made a mistake by tempting Adam and Eve because the divine plan required that they be cast out of the Garden.

A situation in which moral agency operates is one in which good and evil choices comingle. Moral evil is thus understood within Mormonism as a necessary byproduct of agency and an indispensible part of the mortal and divine experience. The Book of Mormon expands on this idea, and explains that existence itself is defined by the presence of two contrasting and competing choices that may broadly be categorized as good and evil, or light and darkness. The absence of either good or evil as options from which to choose is, according to The Book of Mormon, the absence of being.

Another Mormon text, the Book of Moses, provides a poignant demonstration of the power of misused moral agency to cause pain even to God. Enoch, a mysterious figure mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Genesis 5:21-24), is, in this Mormon text, a witness to the weeping of God. When Enoch, utterly shocked by this sight, asks God why he weeps, God explains that the wicked choices of his children will result in their damnation and will thus deprive God of their company. The weeping God of Mormonism is thus a potent symbol of the unbreakable bond between being, evil, and suffering. As long as something is, then evil is a possibility.

In contrast to moral evils, natural evils such as death, disease, and natural disasters are understood in the Mormon context in much the same way as they are in other Christian traditions: as a result of the fall of Adam and Eve. When they were cast out of the Garden of Eden, Adam, Eve, and all of their human posterity became subject to entropy. Their bodies, now mortal, began to decay with age and suffer from disease and the effects of natural forces. Mormons believe that the physical body is a blessing and that every person born on earth will one day be resurrected to live forever with a physical body. The suffering that accompanies the mortal physical body is explained as a necessary part of human experience, and death is as important to the ultimate destiny of each soul as is birth.

- Why is agency the most important principle of moral thought?

- What is the role of Satan in explaining evil?

- Are suffering and evil necessary to the Mormon faith? Explain.

- Describe the Weeping God of Mormonism Why is God portrayed this way?

Afterlife and Salvation

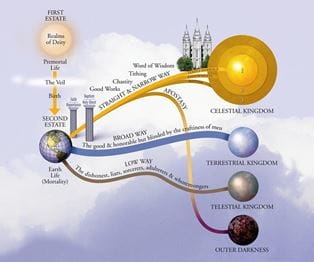

One unique element of Mormonism is the concept of the fate of the soul after death. The founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, eventually developed a view of the afterlife that is much more complex than that held by most other Christian groups. Traditional language of heaven and hell and salvation and damnation do not work well in the Mormon context.

In Mormon teachings, the final judgment comes in stages. The first stage occurs immediately after death. The disembodied spirit is judged as to its general goodness and is assigned to one of two places: paradise or spirit prison. Those souls in paradise enjoy peace of conscience and a time of rest. Those in spirit prison, by contrast, are tormented by guilt and are denied rest. Both groups, however, suffer because they are separated from their physical bodies, something that, according to Mormon scripture, the spirits view as a form of "bondage." At the time of Christ's resurrection from the dead, the inhabitants of paradise were also resurrected. Those who entered the spirit world after Christ's resurrection, however, must await resurrection until the time of Christ's second coming on earth.

Eventually, after Christ returns to the earth, another stage in the judgment occurs. In order to understand this phase, it is first necessary to grasp the three-tiered hierarchy of heavens described by Joseph Smith. The highest heaven, called the Celestial Kingdom, is the destination of those persons who accepted all of the necessary rituals performed by the authority of the Mormon priesthood and who were valiant in their testimony of Jesus Christ.

Mormons believe that missionary work continues among the spirits waiting in prison, and those who accept the teachings of the Church in prison are eligible for the Celestial Kingdom. It is for this reason that Mormons perform temple rites on behalf of their dead ancestors. Irrespective of when souls receive the necessary teachings and rituals, the people who make it to the Celestial Kingdom live in the presence of God the Father and Jesus Christ and are "exalted."

The Celestial Kingdom itself is divided into three parts. Mormon scripture says nothing about the lower two levels, but specifies that only those persons who are married for time and eternity in Mormon temples are eligible for the highest Celestial tier. The next level is the Terrestrial Kingdom, a place inhabited by men and women who lived honorable lives and who accepted the atonement of Christ, but who were not valiant in their testimonies of Christ. Residents of this kingdom enjoy the presence of Jesus Christ, but not God the Father.

The third possible destination of the soul is the Telestial Kingdom. It is here that all those sinners who refused to repent will find themselves. In Mormon theology, Christ's suffering and death make it possible for a sinner to be released from the punishment of misdeeds in the afterlife if the sinner repents and accepts Mormon baptism. Those who do not repent suffer during the afterlife, but even the darkest sinners eventually are redeemed through the atonement of Christ into a realm of glory. While they may enjoy the influence of the Holy Ghost, residents of the Telestial Kingdom are deprived of the presence of the Father and the Son.

At the time of Christ's second coming, those persons who lived lives worthy of the Celestial and Terrestrial Kingdoms will be resurrected and will live on earth under the personal rule of Jesus Christ for a period of 1,000 years. Those destined for the Telestial Kingdom remain separated from their physical bodies until the 1,000-year period has ended. Mormonism thus lacks a traditional heaven/hell dichotomy and offers instead a variety of potential outcomes, based on the willingness of individuals to implement the teachings of the Church into his or her life. Mormons thus speak of those in the Celestial Kingdom as heirs of "exaltation" and those in the lower kingdoms as heirs of "salvation."

In addition to the three "Kingdoms of Glory," a fourth potential destination also awaits certain souls. "Outer Darkness" is a mysterious place that is the home of Satan and those spirits who followed him when he was cast out of heaven at the beginning of time. It is also the destiny of those persons who, while living on earth, had a perfect knowledge of the divinity of Christ but chose to reject him and sin against his teachings. In Outer Darkness, there is endless lamentation and no divine presence. It is the closest Mormon analogy to the concept of hell in most other Christian traditions.

Although the basic contours of Mormon doctrine on the fate of the soul after death have remained stable since the 1830s, the question of movement between kingdoms has been more difficult to settle. In the 19th century, some leading Mormon thinkers held that a soul might have the opportunity to move up from one kingdom to another over the course of the eternities. Since the middle of the 20th century, however, Mormons have taught that there is no movement from kingdom to kingdom after the final judgment is rendered.

- Describe the stages of final judgment.

- How is heaven categorized into a hierarchy? Why is this necessary for salvation?

- What is the Telestial Kingdom? What happens to the individual there?

- Can a soul move through these four kingdoms? Why or why not?