- Trending:

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

RELIGION LIBRARY

Islam

Community and Structure

Hold fast to the rope of Allah, the faith of Islam, and be not divided in groups. ~ Surah 3:105

The Arabic term for the unified community of Muslim believers is ummah wahidah, often simply shortened to ummah. It is the idea of an imagined worldwide community of Muslims united in submission to God. Islamic doctrine teaches that membership in the ummah should transcend geographical, cultural, tribal, and ethnic boundaries. However, recent polling has showed that Muslims' faith is equally important to their nationality or culture. All believers in the ummah are equal, and all members of the ummah are called upon to support, assist, and protect each other.

The term ummah has more than one meaning in Islam. The Quran refers to the ummah as a people singled out by God to receive a prophecy or to play a role in God's divine plan. In the Quran's account, God has created many different ummahs in many different times for many different peoples, sending messengers to each. Most ummahs rejected God's message, and the messenger, but the Muslim ummah accepted God's messenger, changing the cycle of history. (Some Jews and Christians also remained uncorrupted in their acceptance of the messengers sent to them [surah 3:113].)

The Quran also refers to the ummah as a form of citizenship. This civil sense of the term dates to surahs revealed after the Hijra. Shortly after Muhammad and his followers immigrated to Medina at the request of the city's leaders, the Prophet brokered a ceasefire between the warring factions of the town and created a constitution. Called the Constitution of Medina, it declared that the residents of Medina and the surrounding area, both Muslims and Jews, would form a distinct ummah.

The Quran also refers to the ummah as a form of citizenship. This civil sense of the term dates to surahs revealed after the Hijra. Shortly after Muhammad and his followers immigrated to Medina at the request of the city's leaders, the Prophet brokered a ceasefire between the warring factions of the town and created a constitution. Called the Constitution of Medina, it declared that the residents of Medina and the surrounding area, both Muslims and Jews, would form a distinct ummah.

In the hadith, the term was generally used to refer to the spiritual community of Muslims, with less emphasis on the notion of ummah as a social unit. By the time of Muhammad's death in 632 C.E. the meaning had narrowed, referring to the exclusive religious community of the Muslims. This had profound implications in Arabia, where tribal warfare had long been the norm. Under the leadership of Muhammad, and subsequently the first caliph Abu Bakr, tribal and kinship ties were replaced with common membership in the ummah. As Islam spread, the ummah rapidly expanded to include new converts in a wide variety of geographical locations. However, in later times and even today within the post-industrial world, the ummah is usually defined as Muslims living within the same national boundaries or belonging to the same tribe of culture.

Supplanting tribal and kinship ties with membership in the ummah had far-reaching consequences for the development of Islam. In the 8th century C.E., the community reached a consensus that it would be wrong to question the sincerity of another Muslim's belief. The fundamental reluctance to judge the rightness or authenticity of another's belief became an Islamic norm, serving to strengthen Islam's remarkable egalitarianism, and the all-inclusive character of the ummah, which anyone can join. Membership comes either by birth, or simply by sincerely confessing belief in the presence of Muslim witnesses that there is no god but God, and Muhammad is just one of God's messengers.

Supplanting tribal and kinship ties with membership in the ummah had far-reaching consequences for the development of Islam. In the 8th century C.E., the community reached a consensus that it would be wrong to question the sincerity of another Muslim's belief. The fundamental reluctance to judge the rightness or authenticity of another's belief became an Islamic norm, serving to strengthen Islam's remarkable egalitarianism, and the all-inclusive character of the ummah, which anyone can join. Membership comes either by birth, or simply by sincerely confessing belief in the presence of Muslim witnesses that there is no god but God, and Muhammad is just one of God's messengers.

Preserving and protecting the unity of the ummah, whether defined regionally or nationally is an important concern for Muslims, and the community as a whole bears responsibility for this. According to some traditions concerning the Day of Judgment, souls will be collected in groups according to their ummahs, and will be judged according to the actions of the group before being judged according to their individual actions.

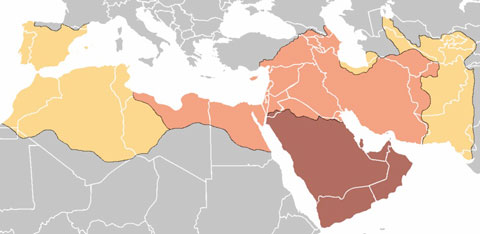

| Rashidun Caliphate | 632-661 |

| Ummayad Caliphate | 661-750 |

| Abbasid Caliphate | 750-1258 |

| Fatimid Caliphate | 909-1171 |

| Ottoman Caliphate | 1519-1919 |

After Muhammad's death the early Muslims agreed that unity would best be protected by a single leader, called a caliph. Under the first four caliphs (the Rashidun) between 632 and 661 C.E., the Islamic empire was ruled by a consensually agreed upon caliph (though there was some dispute by those who later developed into the Shi'a), and the ummah was a political, social, and legal reality as well as a spiritual one. However, historians have argued that there has never existed an Islamic 'state' since this early period because the kingdoms that were created after Ali's assassination in 661 C.E. were Arab kingdoms, and not Islamic ones; they did not adhere to the teachings of Muhammad and the chosen caliphs were merely figureheads of religious authority. After the fall of the Abbasid Caliphate to Mongol invaders in 1258 C.E., the religiously-inspired notion of the ummah survived primarily as a powerful communal reality.

| The Caliphate, 622-750 | |

| Expansion under the Prophet Muhammad, 622–632 | |

| Expansion during the Rashidun Caliphs, 632–661 | |

| Expansion during the Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750 | |

Nineteenth-century European colonialism introduced a host of new issues to historically Islamic lands, including an intricate set of questions surrounding the relationship between national and religious identity. What was the proper relationship between citizenship in the civil societies of nations such as Egypt and Syria, and membership in the universal ummah? What place should religious minorities hold in majority Muslim states? What is the appropriate relationship between one's love of the ummah and one's pride in one's homeland (watan)? These and many more questions formed the agenda for a great deal of 19th- and 20th-century Muslim political thought.

Study Questions:

1. What does it mean to be a part of the ummah?

2. Why is the term ummah interpreted in a variety of ways?

3. What control did caliphs have over the Muslim community?