Because in Western nations the word “ghost” is so often associated with a mental image of a white, sheet-draped figure with oval black eyes, saying “Boooooooo,” the term can be misleading. It is prone to conjure up images that can misrepresent what Buddhists really believe.

Spirits Are Everywhere

That being said, a significant percentage of Buddhists do hold that there are spirits everywhere. Some of those spirits are good and others bad. (Tibetan Buddhism generally holds that there are six post-mortal “realms” of spirits—three upper realms, inhabited by good or better spirits, and three lower realms, inhabited by bad, evil, and tormented spirits.) Contingent upon which denomination one affiliates with, and in which nation one resides, a given Buddhist might believe they are surrounded by the spirits of bodhisattvas, angels, or even gods. Some believe that there are nature spirits everywhere—spirits connected to plant life, bodies of water, and other aspects of nature. Many Buddhists believe in demons, ghosts, evil spirits, and hell-beings.

The idea that these various spirits can possess us is fairly common among Buddhist in certain denominations. As a consequence, some practitioners will seek blessings of protection in order to stave off any adverse influence from demonic or evil spirits. In Thailand and Tibet, for example, there is a common belief that there are good spirits which dwell within you. These spirits are called “khwan” (in Thailand) or “lha” (in Tibet). These good indwelling spirits can actually protect one from the influence and attacks of evil spirits, which might wish to harm one’s health or safety.

Tibet

In Vajrayana (or Tibetan) Buddhism, the belief is ghosts is particularly pronounced. They traditionally hold that ghosts exist in our earthly realm, but they also exist in a realm of the ghosts into which one might be reborn after having lived life as a human or animal. Tibetan Buddhists believe that ghosts can be captured in a trap or even killed, utilizing a dagger called a “phurba.” And, on the 29th day of the 12th month of the Tibetan calendar, there is an annual Buddhist ceremony which seeks to dispel all evil spirits and negativity associated with those ghosts—in the hopes of starting the new calendar year free of such curses and misfortunes.

China and Vietnam

In Chinese, Japanese, Tibetan and Vietnamese Buddhism, they speak of “hungry ghosts.” Not all use the term in the same way but, among some Buddhists, a hungry ghost is a being that is driven be intense needs or desires which cannot be satiated. If a deceased family member is no longer venerated, having been forgotten or neglected by its living relatives, some believe that it can become a hungry ghost. These hungry ghosts can visit the word of the living at certain times of the year to try to fulfill their unmet needs and desires. During the “Hungry Ghost Festival” (in China and Vietnam) family members will put out food and drink in the hopes of satisfying these ghosts, and with the intent of preventing bad luck or other punishments the hungry ghosts might inflict upon them. (Some will also burn “hell notes” so that the deceased will have money to use, or will burn paper effigies of other worldly pleasures, such as cars, television, or even houses—believing that the deceased then have access to a form of the things burned and, thus, be pleased and appeased by the family member’s offering to them.)

Others hold that a person who has committed evils, such as murder or gross sexual sins, may also become a hungry ghost once they have departed mortality. According to some practitioners, a life of greed or lust can also result in becoming a post-mortal hungry ghost. (Many Buddhists believe that there is a post-mortal realm of spirits in which beings dwell prior to reincarnation. It is in that realm, or in the “world of the hungry ghosts,” that one would take on this particular incarnation or spiritual state of being.)

Japan

In Japan, hungry ghosts are perceived by some to be the spirits of those who lived sinful lives, who are then cursed to live as spirits that subsist off of human corpses—spending their nights either scouring for and eating the flesh of corpses, or seeking out the offerings which have been made to or left for the deceased, and devouring those.

Addictions

The term “hungry ghost” is also used as a pejorative name for someone who has unchecked and insatiable desires—in any form. A person who has not learned to control their appetites or passions, or who has succumbed to significant addictions, may be referred to as a “hungry ghost”—though the utilization of this term is traditionally seen as offensive. One source noted:

“Psychologist Gabor Maté wrote a book called In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, where he describes…a notorious neighborhood of Vancouver which has one of the highest concentrations of drug users not just in Canada but all of North America.

The metaphor in the book’s title struck me: The ‘realm of hungry ghosts’ comes from Buddhism. Specifically, it’s one of the six realms depicted in Tibetan Buddhism’s bhavacakra, or ‘Wheel of Life,’ which illustrates the cyclical journey of reincarnation in Buddhist cosmology.

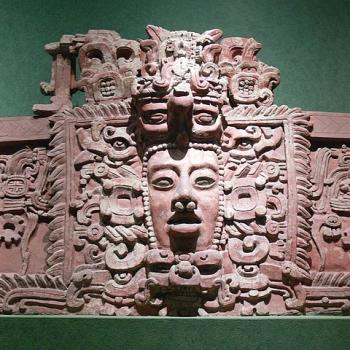

On the wheel, the ‘realm of hungry ghosts’ (preta) is the realm just before ‘hell’ (naraka). These ghosts are depicted with huge bellies and shrunken limbs. They run towards streams only to find them dry when they arrive. They hunger for food, but when they get it, it turns to ash or molten fire in their mouths. The rare times they get what they want, it causes them great agony. Metaphorically, this realm depicts addiction in all its forms.”

As noted, common depictions of “hungry ghost” include huge bellies, symbolic of their appetites or desires that they continually seek to satiate; tinny mouths with a large belly, suggestive that their ability to get enough of whatever addicts them—in order to satisfy their lusts—is nearly impossible; long, skinny throats, representative of the painful process of meeting their addictions; and, sometimes, with a large and bloated belly that itself has a mouth on it, as a symbol that their cravings have a life of their own. Each of these depictions well represent how addictions can rule the live of the addict. They also well symbolize the characteristics of the hungry ghost spirits who, though deceased, also have unsatiable needs that they constantly seek to assuage.

Yes, many denominations of Buddhism teach that “ghosts” exist. While they look nothing like the “ghosts” of traditional Western thought, they are occasionally depicted in ways that might remind one of the ghost (in the original Ghostbusters movie) that “slimed” Dr. Peter Venkman—voraciously gobbling down whatever he could get, and yet never really satisfied.

One scholar of Buddhism noted: “Hungry ghosts are something of an embarrassment to modern Buddhists, who like their Buddhism rational and empirical.” Perhaps, but not all practitioners feel that way. These spirits—whether dead and haunting, or living and addicted—are a strong teaching device in Buddhism, even if one prefers to see them as more of a metaphor than a reality. For Buddhists who traditionally seek to overcome attachment and its consequent dukkha (or suffering), “hungry ghosts” are a perfect representation of our need to believe in the second and third “Noble Truths”—that our craving and attachment cause us suffering, and yet we can break those attachments, leading to the cessation of our suffering and to ultimate release from the round of rebirths.

5/14/2024 8:29:44 PM