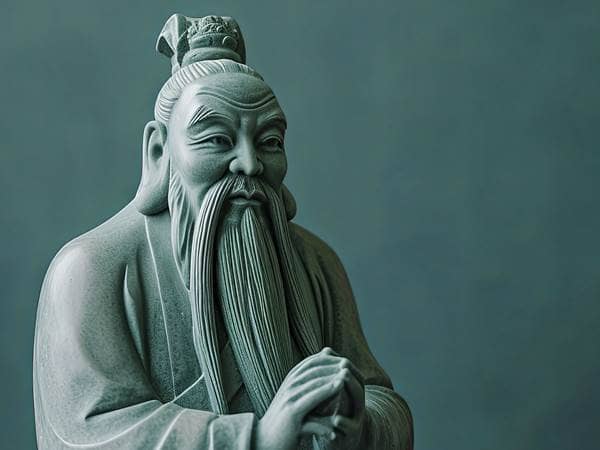

This is actually a somewhat difficult question to answer with a simple “Yes” or “No.” One must take into consideration both what Confucius personally believed (and taught) and what outside influences other religions (like Buddhism, Taoism, and even Shinto) have had on practitioners of Confucianism. Thus, while the “technical answer” to the question, “Does Confucianism have a god?” is “No, not formally,” our response really has to be more nuanced than that.

First, we should note that, while in Confucianism, the place of God has largely been filled by “Tian” (or “Heaven”); nonetheless, many scholars believe Confucius (i.e., “Master Kong,” “Kong Qiu,” or “K’ung Fu-tzu,” as he would have been known) was himself a believer in God. However, like Taoism, Confucianism is more concerned with the here and now—with mortality and morality—than it is with God or the afterlife. Thus, God is simply not a subject of Confucian teachings. Confucius seemed to believe that discussions about God were like putting “the cart before the horse.” In his own words, “Till you have learned to serve men, how can you serve ghosts” or gods? Thus, Confucius didn’t deny the existence of God, but he felt like talking about God was not the way to secure one’s reward in the afterlife. Instead, he focused on the moral development of his people, with the understanding that—for the person who became a “Confucian gentleman”—the afterlife would take care of itself. He certainly believed that heaven (or “Tian”) was the source of any human potential or realization. Nonetheless, Confucius apparently taught that “heaven rarely, if ever, communicated with humans.”

The second thing about Confucianism which is important to understand has to do with how it mixes with other religions and traditions. There is a popular saying, “You are Confucian at work, Taoist on weekends, and Buddhist at death.” This essentially means that Confucianism affects how individuals in certain countries perform their work, Taoism how they spend their leisure time, and Buddhism how they deal with death. But what this saying really reveals is that, in places like Korea or China, it is often very challenging to separate Confucianism from other religions—like Buddhism or Taoism. Indeed, most who consider themselves Confucian also consider themselves Buddhist, Taoist, Shinto, or something else. Confucianism rarely exists on its own. And, thus, many practitioners of Confucianism are also practitioners of something like Buddhism or Taoism. Consequently, many Confucianists may believe in a God (or gods), not because Confucianism teaches them that they should, but because of the influence of other religious traditions on how they live, and even on how they practice their Confucianism. Thus, Boston College’s Professor Silas Wu explained, “Confucian beliefs recognize a supreme reality (or being) in the universe known as Heaven (Tien) or Lord on High (Shangdi), as well as the existence of gods (shen) and spirits (ling). Confucians also venerate celestial and earthly deities (the sun, moon, mountains, and rivers), all of which are presumed to have the power to intervene in human affairs… Heaven had his own will (tienyi) and [it] issued mandates (tienming).” As already noted, most of these spirits, powers, or shen (not “gods” in the Western sense of the term) are the result of the influence of other East Asian traditions on Confucianism. While hard to distinguish from Confucianism itself, they are more the result of the intertwining of various traditions than they are the direct teachings of Confucius himself.

Finally, with the frank acknowledgement that Confucianism doesn’t formally have teachings on the existence (or non-existence) of God, some will be inclined to ask, “Is this then even a religion? Might it better be classified as a system of ethics or a philosophy of life?” Well, technically it is all three of these. Confucianism may not seem like a religion (because God is not the subject of its teachings). However, it does emphasize “heaven,” “tianli” (or the ultimate principle which orders the cosmos, and which permeates everything), making “offerings” to heaven, “xing” (one’s “inner human nature” akin to the “god within”), and even certain “rites.” Thus, it may be missing any emphasis on the existence of God (or the worship of the divine). However, in many ways it functions like a traditional religion, and is certainly intertwined with traditional East Asian religions like Buddhism and Taoism—thereby causing many of its practitioners to believe in something divine, aside from the absence of such a teaching.

4/26/2024 5:56:33 PM