- Trending:

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints History

Early Developments

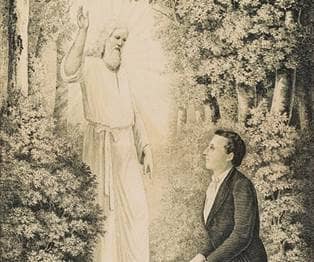

The historical development of the Church may be traced back to the revelatory experiences of Joseph Smith, who claimed to have had multiple encounters with heavenly beings, beginning in 1820. Smith, the son of unsuccessful and migratory farmers who at the time lived in Palmyra in western New York, had this initial experience when he was 14 years old.

Troubled by the competing religious claims and conflicting scriptural views expressed in the camp meetings and revivals that passed through his hometown as part of the Second Great Awakening, Smith asked God directly which church he should join. According to Smith's accounts of the event, he was visited by God the Father and Jesus Christ. Jesus told Smith that the true Christian church was no longer on earth and advised him not to join any of the sects then vying for members in his area.

In 1823, Smith claimed to have spoken with another heavenly visitor named Moroni. This angel, according to Smith, explained that he had been a Christian prophet who lived in the western hemisphere in the 5th century C.E. He had been the last prophet in a civilization that descended from a man named Lehi who had been called by God to leave Jerusalem and travel to the Americas in the 7th century B.C.E. Moroni and his predecessors had kept a history engraved on gold plates, which Smith was to recover and translate.

In 1830, Smith published The Book of Mormon and formally organized a church that was called, at that time, The Church of Christ. In late 1830, on a mission trip to Missouri, several Mormons passed through the small town of Kirtland, in northeast Ohio. While in Kirtland, the missionaries met Sidney Rigdon, a local restorationist preacher who converted to Mormonism in 1830 and influenced many of his flock to follow suit.

The growth of Mormonism in the Kirtland area was so rapid and successful that Smith moved the headquarters of the Church there in early 1831. The Mormons would maintain a headquarters at Kirtland until 1838, during which time they constructed a temple and published a collection of the revelations received by Smith.

Later in 1831, Smith told his followers that God had revealed to him the location of the New Jerusalem spoken of in the Bible. Smith identified the site as Independence, Missouri, and he called on some of the Church's members to leave Ohio and set up a second headquarters in "Zion." Conflicts with Missouri locals over a variety of political, economic, and social issues soon turned deadly for the Mormons. In the fall of 1833, the Mormons were forced to leave Independence, and they established several short-term settlements in Clay, Caldwell, and Daviess counties in Missouri.

In 1837, the community at Kirtland internally collapsed. The failure of the Church's financial institution and a major schism within the Church's leadership structure over Smith's role in the banking fiasco led to Smith's decision to leave Kirtland for the far west in Caldwell County. Not long after, tensions mounted again. In 1838, the Mormons again experienced bloody conflicts with local militia units, which led the governor of the state to order that the Mormons must either be driven from the state or "exterminated."

The main body of members, both those fleeing Missouri and those coming from Kirtland, spent the winter of 1838-1839 in the city of Quincy, Illinois, until Joseph Smith founded yet another city, this time on the banks of the Mississippi River in western Illinois. Smith arranged to purchase 18,000 acres of land in Hancock County, Illinois, and Lee County, Iowa. The Mormons purchased a small town called Commerce on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River, and made it the focal point of their new settlement effort. Joseph Smith re-christened the town Nauvoo, which Smith suggested was a Hebrew name denoting a place of rest or refreshing.

Having learned from experiences in Missouri, Smith sought, and was granted, significant judicial and political power over his new settlement. The secure environment allowed Mormonism to expand and develop theologically and politically. In the years between 1839, when the Mormons arrived in Nauvoo, and 1844, when Smith was murdered, he introduced polygamy, eternal marriage, the temple endowment, the secret Council of Fifty, and ran for president of the United States. The Church also continued its tradition of newspaper publishing with the religiously oriented Times and Seasons and the more politically inclined Mormon Wasp and the Nauvoo Neighbor.

A newspaper led to Smith's downfall. Dissidents in Nauvoo who objected to his growing political power and disturbing new doctrines like polygamy published a call for reform in the Nauvoo Expositor. Fearing it would rile the growing number of opponents outside the city, Smith and the city council closed the paper. Outraged at this affront, his enemies had him arrested. While awaiting trial in nearby Carthage, he was killed by a mob.

Smith's murder in 1844 did not placate the Mormons' enemies. Faced with the threat of invasion and violent expulsion, the Church agreed to leave Nauvoo by the fall of 1845 at the request of representatives of the state of Illinois. Under the leadership of Brigham Young, the exiled group began leaving Nauvoo in February 1846. In July 1847, Brigham Young and his vanguard pioneer company entered the valley of the Great Salt Lake in what was to become Utah territory.

From 1847 until 1890, the Church prospered in the Great Basin as their settlements spread into Idaho, Arizona, California, Mexico, and Canada. Plural marriage, practiced openly in Mormon settlements after 1852, eventually drew criticism and legal action. After years of attempting to establish their constitutional right to practice polygamy, the Mormons finally disavowed the practice in 1890, although it would continue to be practiced in some quarters until the second decade of the 20th century. Today, and for almost 100 years, polygamy is punished via excommunication. With the turn of the new century, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints gained entry into the mainstream of American society, and gradually overcame their identity as alien outsiders.

- How is it argued that Mormonism was formed out of divine guidance?

- Who was Moroni? What did he offer?

- Describe the relationship between sacred space and the origins of Mormonism.

- Explain the role of the media in creating controversy for the Mormon faith.

Schisms and Sects

The belief in continuing revelation, living prophets, and an emphasis on the ideas of apostasy and restoration that formed the core of Joseph Smith's experience and religious message also provided the pattern for schism. During Joseph Smith's lifetime, most of the schismatic breaks occurred over differences between followers and Smith over theological or administrative issues. As early as 1831, some Saints claimed to have been instructed by God to leave Joseph Smith's organization, which the dissenters believed to have lost divine favor, and form separate churches. These early schisms never grew beyond a dozen members and, for all practical purposes, disappeared from history.

The most significant sectarian divides occurred after Smith's death and may be divided into two broad categories: people who rejected the leadership of Brigham Young after Smith's death in 1844, and people who rejected the LDS Church's disavowal of plural marriage in 1890.

When Smith was killed, a power struggle ensued between Brigham Young, who was the president of the Church's Quorum of Twelve Apostles, and Sidney Rigdon, a member of the Church's governing First Presidency but who was disaffected from Smith. The majority of members in Nauvoo chose to follow Young, and this group settled in Utah where they became the largest and most well known of the sects that trace their roots back to Joseph Smith. Those who rejected Young's leadership and Joseph Smith's first wife, Emma, and her children, remained in the midwest, along with large number of scattered believers who were not caught up in the westward movement.

These Mormons began to coalesce in the 1850s, and in 1860 they persuaded Joseph Smith's oldest son, Joseph Smith III, to take leadership of their movement. This group called itself the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and taught that polygamy and the rituals of endowment and eternal marriage were not introduced by Joseph Smith, but were later innovations conceived and implemented by Brigham Young. The RLDS Church, headquartered in Missouri, and the LDS Church, headquartered in Utah, maintained a cold relationship during the 19th century, with Joseph Smith's teachings and legacy as the main bones of contention. After the LDS Church abandoned the practice of polygamy, the relationship between the two main branches of the Mormon movement improved significantly. In 2000, the RLDS Church changed its name to the Community of Christ.

When LDS Church president Wilford Woodruff announced that plural marriages would no longer be performed by the Church (1890), he laid the groundwork for another major schism. Because the practice of plural marriage had been central to the theological identity of the LDS Church in the years after 1852, those who had sacrificed and suffered for their adherence to the principle found it difficult to accept Woodruff's decree. Various Church leaders continued to authorize, perform, and enter into plural marriages for another two decades.

In the 1920s, when the Church began to excommunicate those who married polygamously, several small, family-based sects emerged that claimed to have received unpublicized visits from divine messengers who had instructed them to continue the practice of plural marriage. Following the typical pattern of Mormon schisms, these sects claimed that the main body of the Church had gone astray from divine injunctions and had therefore lost the authority of the one true Church.

Polygamous Mormon sects continue to evolve and develop to the present. In 2006, one such sect, the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, gained notoriety when its leader, Warren Jeffs, became a fugitive. Jeffs was eventually arrested and charged with a variety of crimes relating to marriages of adults to minors in his community. Also in 2006, HBO launched a popular television series called "Big Love," which followed the lives of members of a fictional Mormon polygamous sect.

- When did the most significant divide happen amongst the Mormon followers? What sects did it create?

- Who was Brigham Young? Why was he a figure of controversy?

- What issue strongly divided the two sects? How was it resolved?

- How has polygamy created a sect in contemporary society?

Missions and Expansion

From its inception, the LDS Church, literally following the New Testament injunction to take the Gospel to "every creature," has been a proselytizing organization.The first missionaries were dispatched soon after the publication of The Book of Mormon in 1830. In these early months, the Church focused missionary activity in upstate New York near Joseph Smith's home. By the fall of 1830, a missionary expedition headed toward Missouri in an effort to preach to Native American tribes in that area. On the way west, the missionaries found great success in baptizing members of an offshoot of the Campbellite sect at Kirtland, near Cleveland, Ohio.

For most of the 1830s, missionary work remained concentrated near areas of church settlement in Ohio and Missouri as well as the states in between those two headquarter sites and some parts of eastern Canada. In 1837, however, Joseph Smith sent a small contingent of missionaries to Great Britain. The bleak conditions that prevailed in Britain, and the promise of immigration to America with the "Mormons", added appeal to the religious message that the missionaries carried with them. Between 1837 and the early 1840s, thousands of Britons joined the LDS Church, and most of them migrated to the LDS stronghold at Nauvoo, Illinois. Smaller missionary operations began in French Polynesia in 1843. After Joseph Smith's death in 1844, missions were established in Wales and California. In the 1850s, after the migrant members arrived in Utah, Brigham Young established missions in Scandinavia, South America, Asia, and the south Pacific.

Missionary work continued to expand and spread, and today over 50,000 LDS missionaries serve in the nearly 400 missions that the Church operates throughout the world. Males between the ages of 18 and 26 who are physically, emotionally, and religiously qualified are expected to serve as full-time proselytizing missionaries for a period of two years. Women may serve as missionaries for a period of 18 months after they reach 19 years of age. Although Mormonism is a relatively young religious tradition, nearly two centuries of vigorous missionary work has resulted in the rapid spread of "Mormonism" throughout the world. The Church claims approximately 14 million members worldwide, with more than half of those living outside of the United States and Canada.

Until the mid-20th century, local congregations throughout the world enjoyed a good deal of freedom in deciding how and where to build meetinghouses, what materials to use in Church classes, and how to plan and hold meetings. Today, although there are congregations in most countries of the world, there is very little local variation in terms of worship or teaching. Church classes across the world are taught from coordinated lesson manuals that are translated into scores of languages. The Church's headquarters in Salt Lake City, Utah, employs a process known as "correlation" to ensure that everything published in manuals and other media to be used in Church services is doctrinally sound and otherwise appropriate. The members are instructed that non-correlated materials should not be used in Church teaching or sermons. The global use of a uniform Church curriculum and the centrally controlled content of that material, leave little room for regional adaptations.

The architecture of LDS chapels is similarly uniform. Architects at the Church's headquarters have a small variety of chapel plans from which to choose as they build meetinghouses throughout the world. This is not to say that the Church is insensitive to the needs and circumstances of congregations in varying localities and cultures. Prior to 1980, for example, Sunday meetings were spread throughout the day, with long breaks in between meetings. This model was based on the experience of the Church in areas dominated by "Mormonism", areas in which members lived close to the chapels and could easily travel from home to the meetinghouse multiple times in a day.

In 1980, the Church introduced a new plan that called for a single three-hour block of meetings held back-to-back to more comfortably accommodate the growing number of Mormons living significant distances from their chapels. Similarly, the Church responded to the need for more temples by shifting away from their traditional course of building large temples in areas of relatively high Mormon concentration. In the 1990s, the Church began an aggressive building program to construct small temples in areas with sparse LDS membership in order to ease access for members far from population centers.

In 2019, the Church changed its meeting times and customs to accommodate to its global membership. As of 2023, the Church has 300 temples in various phases of development, active use, and renovation. Currently, there are 172 operating temples all over the world.

- Why is Mormonism a proselytizing religion?

- What is the role of missionaries within Mormonism? Has it evolved over history?

- Explain the Mormonism understanding of correlation. Why is this important?

- How does correlation exist outside of text?

Exploration and Conquest

Early Mormonism was a peripatetic sect. Between 1830 and 1847, the LDS headquarters moved from its birthplace in New York to Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, and the Great Basin area of the American west in rather rapid succession. During the Church's time in the east and midwest, its members remained a minority group and suffered a great deal of violent persecution and cultural disapprobation. Conflicts were particularly intense during the years that Mormonism struggled to establish settlements in Missouri and Illinois.

Between 1831 and 1838, Mormons built and were forced to abandon several settlements, including those at Independence, Far West, and Adam Ondi Ahman. Non-Mormon settlers in these areas disliked Mormon rhetoric and feared the power that Mormons wielded in politics and economics when they voted, bought, and sold, as part of a united bloc.

When the Mormons settled in western Illinois, Joseph Smith sought to ensure a greater degree of autonomy, insularity, and tranquility by seeking a city charter for his settlement at Nauvoo. The Nauvoo charter granted Smith sufficient power to control all administrative and judicial elements of city government. Conflict eventually arose in Nauvoo too, however, stemming externally from jealousy of growing Mormon political power and internally from antipathy to Smith's secret practice of plural marriage. Dissenters started a newspaper, the Expositor, which publicly accused Joseph Smith of sexual impropriety and labeled him a fallen prophet. In response, and with the backing of the Nauvoo city council, Joseph Smith ordered the newspaper's printing press destroyed. Shortly after these events, Smith was arrested on related charges and taken to jail in Carthage, the seat of Hancock county. On June 27, 1844, Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were murdered in the Carthage Jail by a mob. The Mormon settlers of Nauvoo were forced to flee in the years immediately following the murder.

In 1847, a large body of members followed Brigham Young to the West, where they hoped to live in isolation and to practice their religion without interference from outsiders. The Mormons arrived in what would become Utah territory in July 1847, and immediately began mapping and settling towns throughout the Great Basin. Settling in an area that was not held by a single Native American tribe, but that was a buffer between three separate tribes, Mormons and Native Americans coexisted peacefully. Brigham Young originally proposed that a Mormon-dominated area stretching from Idaho to San Diego, California, be admitted to the U.S. as the state of Deseret. This proposal was rejected, and the Mormons ended up settling for a much smaller area that was admitted as the state of Utah in 1896.

In the 19th century, the national press and the American imagination frequently portrayed Utah as a theocracy in which LDS Church leaders ruled in the fashion of the sultans and caliphs that Americans knew about from sensationalized accounts of visits to the near east. Central to this image was the practice of polygamy, which the Mormons openly practiced after 1852.

Plural marriage was an restored religious principle, and was practiced by about 20% of the body of the Church, mostly leadership, from the end of Joseph's tenure through Brigham Young to President Woodruff, but most Mormons living in Utah did not practice it. Conflicts between the U.S. government and the LDS Church over this practice reached their peak in the 1880s, when Church leaders spent years hiding from U.S. Marshals sent to arrest them. Hundreds of Mormon men spent time in prison for practicing plural marriage before the practice was officially abandoned in 1890.

Popular lore notwithstanding, church dominance in Utah remained strong, but not absolute, throughout the 19th century. Brigham Young was appointed territorial governor in 1850, but approximately half of the territorial officers were non-Mormons appointed by the federal government. Young was removed as governor in 1857 as part of an action by U.S. President James Buchanan to quell what he believed to be a rebellion in Utah against non-Mormon territorial officials and judges. In 1869, the completed transcontinental railroad brought increasing numbers of outsiders into the Mormon stronghold. All of these events indicate that, even during the early years of Utah's existence, a non-Mormon presence made itself felt in the territory.

Mormonism has also enjoyed dominance in areas outside of Utah. Despite the fact that the proposed boundaries of the state of Deseret were greatly truncated, Mormon cultural influence has been strong in parts of western Wyoming, southeastern Idaho, Arizona, and California. Mormonism is a global faith, but it continues to maintain its greatest strongholds in the traditional Mormon culture regions of the American west.

- Why did Illinois appear to be a promising settlement for the Mormons?

- Describe Utah, as a territory, when the Mormons settled in it.

- When did polygamy reach its peak within Mormonism? Why was it abandoned?

Modern Age

Modern Mormonism is vastly different in many respects from its earlier incarnations. A convenient demarcation between early and modern Mormonism is the year 1890. In the fall of that year, LDS President Wilford Woodruff declared that Mormon leaders would no longer perform or authorize any new plural marriages. In effect, this "manifesto," as the document came to be known, assured the U.S. government that the LDS Church was in full compliance with the laws of the land and that Utah could safely be admitted to the Union as a state.

It was not until nearly two decades later that authorized plural marriages ceased completely, not surprising given the cataclysmic nature of the shift in practice. Utah was granted statehood in 1896. In 1891, the LDS Church in Utah dissolved its political arm, the People's Party, and Church leaders encouraged individual Mormons to affiliate themselves with one of the two political parties that dominated American politics. This move further diminished Mormon alienation and brought them into greater cultural alignment with the rest of the country. The Spanish American War of 1898 represented the first conflict in which large numbers of Mormons served in U.S. military. From that point until the present, Mormonism has always encouraged military service.

In contrast to the place of Mormonism in American culture during the 19th century, 20th-century Americans came to view Mormons as hardworking and honest. Evidence of this newfound esteem came in the 1950s, when Mormon apostle Ezra Taft Benson served as the Secretary of Agriculture under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Mormons also rose to prominence in the U.S. Military, the FBI, other government agencies, and in the business world. In 2008, Mitt Romney became the first Mormon contender for the presidential nomination of a major political party.

The history of modern Mormonism, however, has not been without its controversies. Since at least the time of Brigham Young, and possibly even before that, persons of African descent were not allowed to hold the LDS priesthood or to enter LDS temples. During the 1960s, the Church faced significant cultural backlash for this discriminatory practice. Some colleges and universities refused to compete in athletic events in which Brigham Young University, the Church's flagship university, was scheduled to participate. Intellectuals within Mormonism found the ban increasingly difficult to understand, while more conservative Mormon leaders and writers fashioned a variety of defenses of the practice, most of which centered on the notion that those persons born through African lineages had been spiritually weak in their lives as spirits before being born on earth. It was not until 1978 that Church leaders rescinded the ban and allowed all worthy Mormon men to hold the priesthood and allowed worthy men and women of African descent to participate in LDS temple ceremonies. While the number of African American Mormons remains small, the Church in recent years has actively preached against racism in all its forms. It refuses, however, to apologize for the racist policies of the past.

Polygamous splinter sects that garner much media attention also pose problems for modern Mormonism. The LDS Church resents the application of the name "Mormon" to these groups and seeks to distance itself from them. The sects that practice plural marriage claim that they are being true to the memory and teachings of Joseph Smith and that the LDS Church has yielded fundamental religious principles in exchange for cultural acceptance.

Since the 1970s, the LDS Church has aligned itself with other conservative religious organizations in the U.S. on issues in the so-called culture wars. Mormon leaders encouraged members of the Church to oppose the Equal Rights Amendment on the grounds that the legislation would encourage women to work outside of the home, thus undermining the stability of the traditional family unit. For similar reasons, in the fall of 2008, the LDS Church marshaled significant support in California for Proposition 8, a ballot proposal that established the legal definition of marriage as applying only to unions as between a man and a woman. Along with conservative Evangelical Christians, Mormon leaders publicly stated their opposition to same-sex marriages and their belief that such marriages represented a threat to civilization.

Despite LDS cooperation with the powerful, conservative Evangelical Protestant churches in the U.S. on social and cultural issues, many Evangelical churches insist that a variety of theological views disqualify Mormonism as a Christian church. Mormonism in the 21st century enjoys less cultural approval than it did in the mid-20th century because of its alienation from progressive secular culture on one hand and the theological enmity of the religious right on the other.

On an organizational level, modern Mormonism is much more sophisticated than it was in the early years. During the 20th century, Mormonism became highly bureaucratized as the Church continued to expand around the world and encountered increasingly demanding and complex circumstances. To serve congregations across the globe, the LDS Church maintains a large translation department and continues to train thousands of missionaries each year in languages needed in the Church's vast proselytizing enterprise. The Church builds hundreds of meetinghouses each year across the globe and now has more than 175 operating temples.

- Was there a connection between polygamy and statehood? Explain.

- How have Mormons been involved with U.S. politics?

- Why was Mormonism controversial throughout the civil rights movement? How was it resolved?

- Why have favorable opinions about Mormonism declined in the 21st century?