- Trending:

- Olympics

- |

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

- |

- Trump

RELIGION LIBRARY

Islam

Historical Perspectives

| The Opening Chapter of the Holy Quran |

|

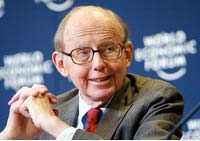

Muslims live in nearly every country on earth, in places as diverse as Paris, Los Angeles, Bali, and Kandahar. They are old and young, male and female, urban and rural, rich and poor, university professors and kindergarten students, parents, farmers, shop owners, and CEOs. Yet dispassionate, even-handed, and data-driven studies of the lives of Muslims and Muslim communities have unfortunately been in the minority of the vast published output concerning Islam in the past thirty years. Concepts such as "Islamic terrorism" and "Islamic fundamentalism" summarily dismiss Muslims as dangerously anti-western. These hasty generalizations saturate the western media, despite the many criticisms of such obvious stereotyping. One of the most disputed theories has been Samuel Huntington's thesis of the post-Cold War "clash of civilizations." Despite its vague and untenable concept of "civilization identity," Huntington's perspective has recently enjoyed both political and popular influence.

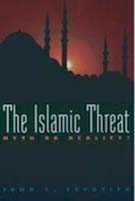

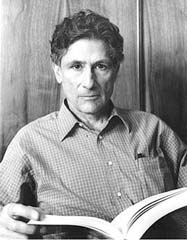

Clichéd views of Islam and the "Islamic threat" proliferate in serious journalism and popular entertainment, despite patient and determined scholarly efforts to dispel them. In The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality? (3rd ed. 1999), John Esposito documented, in expert and accessible terms, the vast diversity in politics, cultural expressions, traditions, and historical realities of the world's Muslims. In The Failure of Political Islam (1994), Olivier Roy described the failure of political Islam to win over the great majority of Muslims. In Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (Vintage ed. 1997), Edward Said discussed the ways in which some of the more crass stereotypes of Muslims have come to dominate American media coverage of the Middle East and the Arabs. In the first section of the book, "Islam as News," Said considers how Americans rely on the news media for their knowledge of Islam and Muslims. In consequence, information is limited to subjects deemed newsworthy, such as oil crises and terrorist attacks. Further, the limited information Americans get from the news media is filtered through American government and industry experts whose overriding concern is to determine who is friendly to U.S. interests and who is not. The result is a distorted view of Islam in which questions of local concerns and experiences are simply not asked.

Clichéd views of Islam and the "Islamic threat" proliferate in serious journalism and popular entertainment, despite patient and determined scholarly efforts to dispel them. In The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality? (3rd ed. 1999), John Esposito documented, in expert and accessible terms, the vast diversity in politics, cultural expressions, traditions, and historical realities of the world's Muslims. In The Failure of Political Islam (1994), Olivier Roy described the failure of political Islam to win over the great majority of Muslims. In Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (Vintage ed. 1997), Edward Said discussed the ways in which some of the more crass stereotypes of Muslims have come to dominate American media coverage of the Middle East and the Arabs. In the first section of the book, "Islam as News," Said considers how Americans rely on the news media for their knowledge of Islam and Muslims. In consequence, information is limited to subjects deemed newsworthy, such as oil crises and terrorist attacks. Further, the limited information Americans get from the news media is filtered through American government and industry experts whose overriding concern is to determine who is friendly to U.S. interests and who is not. The result is a distorted view of Islam in which questions of local concerns and experiences are simply not asked.

Meanwhile, scholarship on Islam has changed considerably in the last thirty years. In the 18th and 19th centuries, European scholars specializing in the languages and literatures of the "orient" (Turkey and the Arab world, and later India, China, and Japan) were called "orientalists." The wars of the first half of the 20th century put an end to the old empires of the Ottomans, Russians, Germans, and Austrians, and then launched the period of decolonization that followed the Second World War. This led to the emergence of orientalist scholars from the very countries formerly governed by European powers and studied by European scholars.

These new orientalists challenged traditional orientalist assumptions, such as the belief that an "oriental essence" could be found within the cultures of Asia. In his seminal 1963 essay "Orientalism in Crisis," Egyptian sociologist Anouar Abdel-Malek argued that the national liberation movements of Asia, Africa, and Latin America demanded a new approach to understanding the problems of the orient. No longer would the peoples of the orient be merely the objects of the scholars' studies; they were the scholars themselves, with their own voices and their own deep interest in the problems of their nations and cultures. Abdel-Malek's essay was quickly followed by a critique of orientalism from the Palestinian Muslim historian A.L. Tibawi. In his 1964 essay "English-Speaking Orientalists," Tibawi discussed European Christian hostility toward Islam, seen most clearly in alliances between 19th-century Christian missionaries and orientalist scholars. These alliances, Tibawi argued, cast suspicion on the objectivity, or so-called "scientific detachment," of orientalist scholarship.

Edward Said's 1978 book Orientalism launched what was by far the most resonant and effective critique of orientalism. Said, a Palestinian Christian professor of English and Comparative Literature, analyzed orientalist scholarship and argued that it serves as a body of hegemonic discourse. Echoing Tibawi, Said discussed in great detail the failure of orientalist scholarship to adhere to such core intellectual virtues as rationality and objectivity. What orientalist scholarship does is create stereotypes through which power over Muslims peoples is asserted and justified.

Edward Said's 1978 book Orientalism launched what was by far the most resonant and effective critique of orientalism. Said, a Palestinian Christian professor of English and Comparative Literature, analyzed orientalist scholarship and argued that it serves as a body of hegemonic discourse. Echoing Tibawi, Said discussed in great detail the failure of orientalist scholarship to adhere to such core intellectual virtues as rationality and objectivity. What orientalist scholarship does is create stereotypes through which power over Muslims peoples is asserted and justified.  Instead of approaching the study of Islam or Muslims in terms of specific questions about local circumstances and historical influences, orientalism carelessly portrays all Muslims in an undifferentiated mass, describing them as irrational, backward, despotic, inferior, and so forth. The West is then by extension stereotyped as rational, progressive, humane, superior, and so forth. Other orientalist stereotypes include such untenable concepts as the so-called "Arab mind" and "Islamic society." Echoing Abdel-Malek, Said argued that whether consciously or not, the orientalists had created a discourse that serves to justify European, and subsequently American, imperialism.

Instead of approaching the study of Islam or Muslims in terms of specific questions about local circumstances and historical influences, orientalism carelessly portrays all Muslims in an undifferentiated mass, describing them as irrational, backward, despotic, inferior, and so forth. The West is then by extension stereotyped as rational, progressive, humane, superior, and so forth. Other orientalist stereotypes include such untenable concepts as the so-called "Arab mind" and "Islamic society." Echoing Abdel-Malek, Said argued that whether consciously or not, the orientalists had created a discourse that serves to justify European, and subsequently American, imperialism.

Said's critique of the power exercised by scholarly discourse about "the Other" (those who are not us) sent shockwaves through academia, permanently altering the dynamics of such established disciplines as anthropology, history, sociology, and comparative religions. Many now seek to study Islam and Muslims with careful sensitivity to their own inherited assumptions. While Said has been rightly criticized from a number of positions, the majority of his critics accept his conclusions in principle.

Others, less interested in entering the debate over the validity of Said's claims, have taken his argument into the field to conduct fresh analyses of Islamic cultures and histories, and of the colonial empires that sought to subjugate the Muslims. Through this fresh and original scholarship, the richness and density of our shared knowledge on Islam and Muslims is increasing. For excellent examples of studies of the diversity and complexity to be found within specific localities and historical moments, see Yann Richard's Shi'ite Islam: Polity, Ideology, and Creed (Blackwell 1995), Peter Lamborn Wilson's Scandal: Essays in Islamic Heresy (Autonomedia 1988), or Lisa Lowe's Critical Terrains: French and British Orientalisms (Cornell 1991).

Others, less interested in entering the debate over the validity of Said's claims, have taken his argument into the field to conduct fresh analyses of Islamic cultures and histories, and of the colonial empires that sought to subjugate the Muslims. Through this fresh and original scholarship, the richness and density of our shared knowledge on Islam and Muslims is increasing. For excellent examples of studies of the diversity and complexity to be found within specific localities and historical moments, see Yann Richard's Shi'ite Islam: Polity, Ideology, and Creed (Blackwell 1995), Peter Lamborn Wilson's Scandal: Essays in Islamic Heresy (Autonomedia 1988), or Lisa Lowe's Critical Terrains: French and British Orientalisms (Cornell 1991).

Study Questions:

1. What contributed to the identity of Muslims as “anti-Western”?

2. Describe the relationship of the media and Islam in the West.

3. Who is Edward Said and what does his book Orientalism contribute to the discourse of the creation of Islamic identity?