By Hadia Mubarak

During my freshman year in public high school, my English literature teacher took me aside after class and asked me, “Did your parents force you to wear that?” referring to my headscarf. I distinctly remember the feelings of confusion, surprise, and anger I felt, wondering why she would assume that I was being forced to cover my hair. Twenty-five years later, I am no longer surprised by my high school teacher’s assumption. I now understand her question as the natural byproduct of decades of Western representations of Muslim women in literature and popular culture.

Western literature and more specifically, American popular culture has been long infatuated with narratives of abused Muslim women whose lives are presumably characterized by force, bondage, and cruelty. Such narratives occupy a special place in the cultural imagination of many in the West. These narratives are never really about Muslim women; they are about us. More specifically, they represent what we are not. Such narratives serve to reinforce a construct of the Muslim world as uncivilized, backward, violent and oppressive. They fall into the genre of “pulp non-fiction,” as termed by scholars Dohra Ahmed and Lila Abu-Lughod. This imaginary construct of Islam as representing the civilizational “Other” allows us to define our own civilization, the West, based on what we are not. In reference to Islam as representing the antithesis of Western civilization, Samuel Huntington wrote in his book, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, “Unless we hate what we are not, we cannot love what we are.” Never mind that Islam is a global religious tradition that transcends the East-West binary and has roots in the United States since the first slave ships arrived in Plymouth Rock in 1619.

Stories about abused Muslim women occupy a special place in Western literature because they allow us to construct a juxtaposed narrative about who we are, as Americans and Westerners, more broadly. In contrast to stories about downtrodden Muslim women whose sexuality is forcibly repressed, we hold up a mirror against our own cultural self-image, the perception of ourselves as free and liberated, as a civilization where women have agency and where we celebrate female sexuality. For this reason, most narratives about the “downtrodden Muslim woman” are attentive to the Western gaze. As World Literature Professor Mohja Kahf notes, the Orientalist “victim narrative” has been adapted today into the “victim-escapee” narrative, in which the victim “casts off the shackles of Muslim patriarchy all by her Nancy Drew self. Then she runs into the arms of the waiting West or at least embraces Victoria’s Secret shopping spree.”

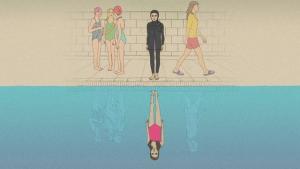

This trope is most evident in a short film, Swimsuit (2000), directed by Hasan Hadi and currently featured on HBO Max. The film is about an adolescent girl who desires to “escape” the burkini that her conservative Arab Muslim mother has “imposed” on her. Throughout the 11-minute film, the protagonist, Samah, looks longingly at the bathing suits worn by the other girls on her swim team. The viewer sees in her eyes the longing for sexual liberation, reinforced by a short slow-motion scene in which she tries on a hot pink bathing suit, strutting in front of a mirror, her long brown hair flung over her shoulders. In this short scene, the viewers become privy to Samah’s repressed desire for sexual freedom, the desire to flaunt her body without the cultural reservations that her mother allegedly imposes upon her. It is the only scene in this 11-minute film in which Samah flashes a big smile, which she captures in a selfie-and post on Instagram. She decides to keep the Swimsuit and stuffs it in her backpack, the Swimsuit assuming the symbol of her desire for “freedom.” Like all victim-escapee narratives, Western culture is always propped up as the civilizational norm, the standard of freedom to which our victim Muslim girl aspires.

Whether or not the film director, a male, intended to juxtapose Islam and the West as polar ends of a civilizational spectrum, this is the message his film ultimately sends. In the privacy of her locked bedroom, far from her mother’s judging gaze, Samah cuts out magazine clippings of scantily dressed women (who all happen to be white) and saves them in a little vignette box. First, what is an 11-year-old girl doing with tabloid clippings of female models in underwear and bikini? By juxtaposing the images of these white women in bikinis and bras with Samah’s conservative mother, who wears a hijab outdoors and buys her daughter a burkini for her swim meet, the film plays into the classic binary of Islam as “sexually repressive” and the West as “sexually liberal.”

The director further plays on common tropes of this genre by contextualizing Samah’s story through culture. From the Arabic calligraphy over the family’s front door displaying the religious phrase, “as God willed” (ma sha Allah) to the mother’s customized ringtone set to Ya Tayba (a song in praise of Prophet Muhammad) and the film ending with the Arabic Sesame Street theme song, the director invites us to view Samah’s story through a cultural lens. Just like readers of pulp non-fiction, viewers of this short film believe they are learning something about Arab culture when watching this film, not just the particular experiences of this young protagonist, who desires to be like everyone else on her swim team.

Ultimately, the film does a huge disservice to Muslim girls and women who choose to wear hijab. It grossly misrepresents the experiences of millions of women, particularly those in the West, for whom their hijab is a choice and a marker of religious identity. By depicting this young Muslim adolescent as ashamed by her Muslim attire, the film actively erases the ingrained confidence that many Muslim women feel when they wear the hijab – confidence without which many could not wear the hijab. It takes courage and confidence to withstand the social pressures to conform, to stand out and stand up for what you believe, despite decades of distorted representations. For many Muslim women, the decision to don the headscarf in public is a statement of their desire to live God-conscious lives, regardless of people’s perceptions of them. The Swimsuit had an opportunity to complicate and correct the single narrative that has been rehashed about Muslim women, but it utterly failed. Rather, it reinforced the image of Islam and Muslims as the cultural “Other.”