Source: Flickr user jean louis mazieres

License

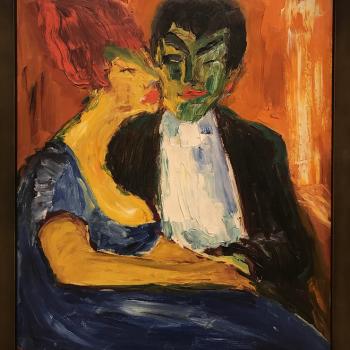

Technically speaking, “melodrama” has little to do with the Greek word for “honey” (meli). But what’s the fun in what’s technical? Melodrama teaches us to be suspicious of the technically correct and attentive, rather, to the emotionally astute. Melodrama touches the spirit of the law and not the letter. It oozes, too sweet and rich—mere soap opera—for some. However, for those of us believers with a sweet tooth, it offers pleasure and insight in a way simultaneously filling and sickening. It is the Halloween candy haul of dramatic forms.

Few such hauls are more rewarding than Todd Haynes’ Far from Heaven (2002), a spiritual successor to (or even remake of) Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955), informed by R.W. Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974). Ali itself is a German redux of the Sirk movie that takes the age and class distinctions between Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman’s characters and adds a racial dimension. Haynes takes Fassbinder’s extension of the text’s central message and pushes it yet further.

Cathy Whitaker’s (Julianne Moore) husband, Frank (Dennis Quaid), loiters. Or, at least, that’s why he’s arrested. Their perfect, 50s suburban life starts to tear at the seams when she catches her better half necking with another man in his office after hours. She turns to their new gardener, Raymond Deagan (Dennis Haybert), for comfort. Raymond is Black, and Connecticut society in the 50s stands firmly against interracial love, even when it’s sublimated into intimately understanding friendship. This is melodrama. We know nothing good can be in store for these tragic souls.

Like Sirk’s films, the narrative’s deep sadness calls for a lush atmosphere. Haynes used 50s incandescent bulbs, period lenses, and everything else he can get his hands on to make the film “authentic.” It works. From Julianne Moore’s scarves and bruised forehead to the shimmering leaves and vibrant townscapes (the film was partly filmed only five minutes from where I’m writing this!), everything is gorgeous. The point is the disconnect between inside and outside. Convention traps these people.

Frank can give up his life—for what? To move to San Francisco? He doesn’t seem like he’ll do well with the Beats. But it’s an idea. Raymond cannot speak to Cathy without getting stones thrown though his windows, tossed as often by members of his own community as by white people. Their harassment makes a grim kind of sense. Why invite attention? Why risk the community and its safety? For what? For one guy’s fleeting happiness?

The white people of the town have nothing but disdain for Cathy. Where does an interracial couple move in the late 50s, anyway? Such poor souls didn’t even have a San Francisco or the Village.

As Haynes himself has said, echoing Fassbinder, the seeming pessimism of these too-delicious treats is in reality a species of optimism. By observing the constraints that hold back characters and their inner lives, we get a glimpse of the potential for a better world.

For me, however, it is melodrama’s insistence on the mutual implication of the social and the individual that always stops me in my tracks. Cathy, Frank, Raymond—the whole lot—live and breathe in and through both their desires (socially informed, privately cultivated, even hidden) and their roles (as businessmen, housewives, gardeners, etc.).

Isn’t to be human to be caught in just that trap? Whatever true self we want to discover, that we seek deep down, ends up implicated—from its very origin—in otherness, in the desires, needs, and expectations of the world around us. Frank hits Cathy. He struggles with himself and cries. Cathy reaches out to Raymond, only to reject him. El (Patricia Clarkson), Cathy’s friend, has sympathy. But only up to a point.

No man is an island. We might add, after a watch of Far from Heaven, that all people can be sweet in their sickness and sickening in the sweetness.