THE S.S. CHUSAN

Vera Johnston

July 4 1890, Near Aden On The Red Sea.

My two large Chinese vases were smashed to smithereens. A piece of white tulle, embroidered with gold, and the wings of those bronze-green Madras beetles were completely soaked, and stained the color of the red silk pillowcase in which I placed it. How many clay idols were crushed and crumbled! And my gorodnichya! My God, what troubles did the merciless monsoon cause to my gorodnichya! I sat on the deck and sadly thought about this topic. We had finally left the storm area. The sea calmed down and glistened with a blissfully indifferent smile. The water rose up in millions of microscopic bubbles from beneath the steamship’s keel, as if we were floating through the abyss of seltzer water. A hot breeze from the shore drove herds of red, large, long-legged locusts.

The butcher on the steamship, who in the first days of the voyage was attached to my enemy, the milk cow, as if it were his own child, told me what a poor martyr she was, and was glad that she would rest on land when Siam (which had suffered so badly) was being repaired.

“Look at her legs,” he told me.

I looked. Indeed, the hooves were white, spread out from standing on the boards for a long time. Everyone approached the cow, and noticed that she was a real English cow, that is, large, without humps, white with brown spots, and not dirty-gray, like all cows in India. Everyone patted her on the neck and said: “dear old cow,” and one merry fellow among the officers blew cigar smoke into her nostrils, for which the butcher was very angry.

Port of Aden, Arabia. [1]

Finally, the rocks that had been visible for a long time, pushed out of the water by an underground force, parted, and the white houses of Aden appeared in all their barracks-like charm at the foot of the black cap-shaped mountain. What a terrible place Aden is! Nothing ever grows here. Lovers of greenery decorate their terraces with painted tin cacti. One lady I know had, when she lived in Aden, a green rug with long wool so that her children would not miss English lawns. Vegetables and fruits are brought from Egypt. The cisterns in the courtyards are filled with rare rains, the only natural water in Aden. When the cisterns dry up, which happens for several months every year, water is brought from India or Europe. In order to understand the entire unattractiveness of this city, it is enough to say that not a single traveler who missed the land before illness was ever tempted to land on the shore in Aden, even if the steamer stood there all day.

The only thing worse than Aden is the island of Perim, in the very strait from the ocean to the Red Sea. The English tell two funny legends about it. The first was about how the British took possession of it. Perim is so inhospitable, useless, and small that even the British did not want to designate it with the letter A in brackets on geographical maps. One fine day, a French squadron suddenly appeared in sight of Aden. The Governor-General of Aden looked through the telescope, and directed his men to find out what the Mossu needed. (Mossu was what “John Bull” called the French.)[2] Both nations saluted each other and fired cannons. The French were invited to a feast by their British hosts. The cunning Mossu pretended to be on a routine patrol, but over the course of dinner, with copious libations, the French captain became suddenly sensitive, and admitted that they had come to take possession of Perim. Encouraged by the kindly words of the governor of Aden, the French captain said, “la belle France, sa patrie,” (“beautiful France, his homeland”) had hopes of regaining the island of St. Mauritius through dominance in the Babel-Mandeb Strait. The Briton pretended to be terribly sympathetic to the holy cause, and promised armed assistance should the need arise, which, of course, would not present itself “since on Perim not only were there no people, but there was not even insects.” The following day, when the French squadron, ready for battle, approached Perim, its commander was met on the shore by the governor’s adjutant, who had quietly disappeared the day before at the Aden feast to settle there. The British flag fluttered on the island, and the sailors accompanying the deft adjutant, began building an English lighthouse.

Another legend tells of an Irish lieutenant assigned with a team of sepoys to monitor the Perim lighthouse. Perim had already been British territory for several years, and the Aden governor was ready to lose his head, since not one of the lieutenants sent to the island survived there for even six months. One went crazy, another drank himself to delirium tremens, the third threw himself from the lighthouse into the sea. Finally, Lieutenant O’Flynn volunteered to go there. To the delight of the governor, O’Flynn not only lived there for six months, but for an entire year, and then a year and a half, and two years. All the time he wrote reports filled with contentment with his fate. Finally, it turned out that O’Flynn had been living in London the entire time, calmly composing reports in his club, and sending them to the governor from Perim, with the help of his faithful sepoy. Now they no longer send lieutenants to Perim.

The Siam finally dropped anchor and stood two fathoms from the masts of a large steamship, sadly sticking out of the water. It belonged to the French company Messagerie Maritime. It was so beaten by the monsoon, that it could not reach the shore, and sank in sight of Aden. There were more than three hundred people on it, and everyone, they say, was saved.

We thought that we would be immediately transferred to a new ship of the P&O Company, and everyone pulled their luggage onto the deck. But we had to wait a few more hours baking directly under the unbearable rays of the sun. It was exhausting protecting small luggage from the thieving sons of Arabia, who poured onto the ship from all sides for to sell ostrich feathers and eggs, or the helical horns of some mountain goats, and to secretly steal anything they could. No matter how they were pushed away, almost throwing them overboard in some cases, there was no way to get rid of them. The Arab boys, especially, were jumping around us and chanting, “Give me a shilling!”

We waited so long that we would have been completely bored if it had not been for Lieutenant N., gifted us a performance. Some, evidently, important missionary from the first class, having learned that Lieutenant N. had been bitten by a “mad dog,” wrote him a letter. It was full of consolations and exhortations for him to turn to the Anglican Church, and consider it as a loving mother, and urged him to repent before the terrible death awaiting him, that he may be saved “from the even more terrible torments of hell.” English missionaries generally know hell and the devil very well, and use their services in converting Christians much more than preaching love. Lieutenant N. read the letter publicly, with his own additions and comments, howled several times and finally fainted. However, I am sure that the missionary’s letter excited Lieutenant N. Having recovered from his fainting spell, he decided to play chess, but the chessboard turned out to be occupied by two postal officials. The violent lieutenant snatched the board from their hands, scattering the checkers and pulling out a chair from under one of them, looking as if they were something that could not be noticed. The brown face of the enraged postman was covered with yellow spots, he flew at the Englishman, trembling with his whole small, thin body, like an angry cockerel.

“Whom are you insulting? Who do you dare insult?” he repeated in a voice that was teetered from rage and tears. “Whom?”

“You,” the officer calmly answered, sitting down to play chess.

But this did not stop the poor postman from playing. Seeing this, Lieutenant N. snatched the stick from his hands, swung at him and hit him twice with all his might. All the other postal officials came running to help their comrade. It was a disgusting mess. No more than an hour later, I again saw the victim hovering around the same officers, but completely calm, and trying to enter into a peaceful conversation with one of them.

Quarter Deck, S.S. Chusan, Bay of Bengal, 1890. (Source: Wiki)

A steamer finally came for us, which was to take us the rest of the way to Europe.[3] The large and fast Chusan, so-named for the Chinese island from which it sails to London, had crossed the Monsoon region in only three days. Charley looked completely different; much healthier, and with more vigor. The transition from storms to peace, from all kinds of troubles to comfort, was so sudden and complete, that life on Chusan will forever remain one of my best memories. From the gray-haired, stately captain, who came to us every morning with the doctor, and the officer on duty, to inquire about our happiness, to the last sailor, everyone seemed affectionate and sociable. Everything looked welcoming.

The first days after Aden on the Red Sea there was nothing to see except bright water, and an even brighter, cloudless sky. We had to be content in exclusively looking at each other, and the ship’s inhabitants. Our life flowed quietly, calmly, and evenly. In the mornings, when the sun had not yet had time to heat up the ship, we all paced back and forth, like animals in a cage. Before evening, which on the Red Sea comes, as in India, immediately, without twilight, the passengers amused themselves by throwing tight rope rings into a tub at a distance of several steps, or bags with lead weights on a board lined with numbers. In the first game, a distinguished young Chinese boy was unable to say anything in any European language, except that he was traveling from Singapore to Marseille. After a late lunch we went below deck to sit in the cool, dark, and drank beer, smoked, and listened to music until it was time to go to bed.

Deck quoits on a P & O Liner.[4]

The music was completely different than on Siam. Among the musicians, one in particular stood out, an elderly red-haired captain’s mate. He played a medley on the violin of Bellini’s Norma and Meyerbeer’s Robert Le Diable, to the accompaniment of one of the widows. There were several widows with us, as was often the case on colonial steamers. If Noah’s Ark was inhabited by people of different nationalities instead of different breeds of animals, then it would resemble the steamships which sailed from the colonies to Europe.

Among the passengers and employees, we had on board the Chusan, Englishmen, Irishmen, and Scots; Frenchmen and Greeks, a Russian, and the young Chinaman. The captains, their assistants, doctors, chief barmen, etc. were usually of the same nationality: French, English or Italian. The sailors are all Indian Muslims, dressed in tight, red, flat-topped turbans on their shaved heads, long-skirted cassocks made of blue canvas and white trousers dangling on their thin legs, trimmed at the end with a ribbon or even stitching out of coquetry. Generally black laborers, like the stokers, were from Mozambique, or from the south of India, where former slaves of the African tribes, lived in a large colony, without mixing with the indigenous population. Their clicking and lisping was a very distinctive addition to the guttural speech of the sailors, and the various expressions of European speeches heard in all parts of the ship. Their dress is unique, in that they don’t dress at all, only occasionally, when it gets cold, do the cover themselves with dirty rags.

The first day we spent on the Chusan was a Sunday. Usually on a ship there was at least one clergyman among the travelers. He would be invited to the first class wardroom, and some Christian sailor would go around all the cabins, occasionally knocking on a ringing gong, and everyone would gather for mass.

I did not go to the Anglican Church, as the first-class hall was called in such cases, but went downstairs to get the Gospel, and began to read, sitting in the shade. But I didn’t manage to read properly. Very soon some curious, blue-eyed children with blond heads began to peek out from under the life-boat where I was sitting. These were the children of a widow traveling from Hong Kong. It had not been six weeks since the death of their father, an English soldier serving in China, and their mother had not yet recovered from the first pangs of deep grief. The children were completely left to their own devices. There were seven of them, ranging in ages from nine to two years old, they were fed by either one of the compassionate passengers, a maid, or the dark sailors whose chief characteristic, I found, to be their tender love for other people’s children. Every now and again one of these sailors would catch a child en route to the ground when they fell from a steep staircase; they also removed the children from the rails when they looked as though they would fall into the sea.

An illustration by Charles Guillaume in Paul Bourget’s Mensonge.

I was sorry to drive them away from me at the first meeting, and no matter how hard I tried to keep them in order, they did not allow me to finish reading the chapter. To avoid the political conversations that bored me (even with baby Johnny) I began to show him, and his sisters pictures in Paul Bourget’s Mensonge. I then invited the whole company of children to go see the menagerie of monkeys and parrots which belonging to the sailors. With great difficulty we descended from the spiral staircase to the lower deck, and one of the younger girls screamed and hid in the folds of my dress, frightened by the faces of the sailors who helped me with unspeakable kindness during the crossing.

The care and tenderness with which these people treat their pets, all kinds of animals, is positively touching. On the Chusan there were half a dozen small monkeys, a cat with kittens, some rabbits, and a dog with one ear sticking out and the other stubbornly bent down. These already busy sailors managed to look after, and tidy up, this fussy little world. Every day the senior sailor separated small piles of rice with lamb and vegetables for each of his pets. They knew when the lunch hour came, when the sailor blew the whistle on his silver chain. An old, gray-haired black man was tasked with getting fresh cabbage and carrots for the rabbits. We were often amused by the sight of the cooks chasing this thief with pots and rolling pins; but the man deftly ran away from them, and climbed onto the masts, all the while taunting them with grimaces. Charley and I offered him money to buy vegetables every day, but he refused. It was probably more fun for him this way. The Italian sailor had several learned mice. Above our heads, parrots swayed and chattered non-stop, a starling whistled, and many cute little Indian birds jumped in cages. Both the children and I myself fell in love with this menagerie and often visited it, always warmly received by its owners.

Before arriving at Suez, we all noticed a crowd of sailors who were shouting and waving their arms so much that if Tartarin had been among us, he would certainly have thought it was a riot on the high seas, but it was just a bunch of sailors who decided to pierce the ears of two newborn monkeys, and were discussing what shape of earrings they would buy for them when they went to the Suez Bazaar.

We often looked at Muslims praying with Europeans unceremoniously. In general, they strictly observe their customs, but here they were also influenced by the proximity of Mecca to Medina. At sunset, the sailors positively froze on their knees with their hands raised to the sky, looking straight after the luminary descending onto its watery bed.

There was one ugly, but very entertaining, Englishwoman who was traveling with us. We called her “Stanley,” because she wore the same exact linen cap with a visor that the explorer, Henry Morton Stanley, was typically depicted wearing. This “Lady Stanley” constantly admired the prayerful ecstasy of Muslims, and on one occasion she had a clash with that missionary who wrote a letter to Lieutenant N., calling for repentance.

“Look at them,” she said once, looking at the praying sailors. “Which of us would have the deep feeling to go into prayer like that, despite possible ridicule, without being embarrassed by anyone’s presence?” That’s courage and high faith!

“Madam, let me tell you,” the missionary, touched, quickly intervened. “Muslims are the same rude pagans as the rest of the world who do not belong to our church.”

But having met sharp rebuff, the missionary did not object, and soon left. We thought that would be the end of it. But the next day, to our mutual surprise, the children began to apparently run away from Miss Stanley. I called one of the girls over and asked what was the matter.

“Mama says she is a bad lady!” was the answer. “Mom says she’s a nasty lady—”

“Why is that? She has been, after all, very kind to you.”

I knew that. Having traveled with them from the beginning, “Lady Stanley” took an active part, both in words and deeds, in assisting the widow and orphans.

“Yes, but now mom doesn’t want the children to play with her, and I myself won’t associate with her,” the girl repeated. “She doesn’t believe in God.”

“But who could tell you such a lie?”

“Reverend Smith. He’s telling the truth—Mama says that she is no good.”

It turned out that the missionary had visited the widow, and asked about her late-husband, and the future of her children. In this way he managed to turn her against the person from whom she had seen nothing but good for over a month. Protestantism—especially its sects—have far exceeded the Catholics in their intolerance, although the entire Protestant north of Ireland does nothing but cry out against the immoral intimidations and intrigues of the Catholic clergy in its southern counties.

The steamship entertainment, including games, monkeys, and pleasant conversations, began to become boring for everyone. Everyone wanted to see land again. Out of boredom, the gentlemen officers came up with the idea of “Englishizing!” as they put it, the little Chinaman who was traveling with us. They laughed terribly when, after the first glass of whiskey and soda, he started to braid his legs.

Finally, in the evening, already on the fifth day after Aden, we saw the rocks that gave the sea its name. How many silent millennia has it watched over this deserted coast I wondered. The rocks crush the traveler’s soul with their unpleasantness, and their eternal loneliness. Everything was dead around them. Sometimes only winged fish swam in schools from wave to wave, basking and playing in the sun. At night, only luminous sparks, and spots, scattered across the dark waters, mixing with the reflections of the stars, which seemed to be trying to discern from the heavens what kind of silent child was born there, below the darkness and desert.

The cliffs of the Red Sea are scary, but beautiful. When the sun shines high, they bashfully hide in the haze of hot light. But in the evening, when the sun has already disappeared behind them, yet still burning and glowing around them, they are even better. The dark green sea, the bright yellow sands at the foot of the sparkling brown mountains, the scarlet glow above them, and even higher the blue sky, and the higher the bluer heavens, until, finally, huge, brilliant stars make everything seem dark and insignificant. Not a single painter would dare to put such bright colors next to them as the Red Sea sparkles. If they did, no one will believe them.

One night I climbed to the very bow of the steamer, so that behind the thin railings the desert began. The sea sparkled with phosphorescent sparks; the ship was shrouded in a light fog. The brightness of the stars in the south was still new to me at that time, and I absolutely could not distinguish where the water ended and where the sky began. I looked straight ahead, where the noisy steamer did not precede me. I stood enchanted in some in-between, transparent, and luminous space, not on earth but not in heaven. It was frightening.

The shores of the Red Sea became so familiar to me that they seemed very prosaic to my eyes. As we approached Suez, the water changed its color, from transparent dark blue it became a more vibrant blue, as if mountains of blue were first thrown into the sea, and then starch was added so that it brightened and became cloudy. At Suez itself, the bottom is so shallow, and the red sands so close to the surface, that the water becomes cloudy green, and fades like stale turquoise long-unworn.

It was about one o’clock in the afternoon. We decided not to go ashore, knowing that tomorrow we would have a long layover in Port Side, which was exactly like Suez. Chusan was very soon besieged and taken in battle by many different tribes seeking profit.

Turkified Europeans in fezzes and cigars, and Frenchified natives of every tribe, were selling piles of photographs of Egypt, the Red Sea, and the Suez Canal (with its two cities,) and a whole flood of portraits of Ferdinand de Lesseps, who created the Suez Canal and Port Said out of nothing. For the thousands of people who live at the opposite ends of the Suez Canal, and who depend on the commerce of these sandy places, Lesseps was an incomparable hero, like some kind of mythological demigod who lived in their hearts. Centuries will pass and, perhaps, everything created by this man will be swallowed up by the insatiable desert, but the memory of him will not disappear, and if some clairvoyant medium comes to the future desert in this place in a thousand years, he will see in the ether countless reflections of Lesseps’s photographs, trembling in the sky, appearing on the sand, and swaying on the distant waves, Lesseps sitting. Lesseps standing. Lesseps en face, in profile, with his family, and alone.

More and more boats moored to Chusan every minute with traders, and idle onlookers who were in a hurry, but, as was the habit of southern peoples since the railway was built to Suez from Cairo, looked aimlessly at people, and showed themselves to the new passengers from the centers of the country. The crowd on deck was getting thicker; there was nowhere to go due to the being goods thrown everywhere. Someone, either an Italian or a Slav, I could not tell, was enthusiastically playing “Love, the Child of Inconstancy,” on the concertina; squinting, nodding his head, and moving the instrument away and pressing it back against his chest. The flashing of hundreds of faces, fezzes, several silent steamships, ships frozen in motionlessness and sleep. To the right were the same scorched cliffs, to the left, beyond the bright sea, was another sleepy town with yellow and white boards, red roofs, and rare clumps of greenery. Behind it was sand; sands stretching as far as the eye could see.

“Lady Stanley” called me from the lower deck. “Why are you hiding? There’s an amazing magician here!”

I have seen many very clever magicians in India, so I did not expect anything special this time, but I was surprised by one of the juggler’s tricks. It cannot in any way be explained by ordinary sleight of hand, nor clever deception of the eye with the help of preprepared boxes with a double bottom, threads, magnets, and the like.

The missionary stood closest to the magician, and in appearance, he was the complete opposite of the magician, a son of the desert. The missionary’s face was grumpy with evident signs of displeasure and, perhaps, even some fear. With visible annoyance, the missionary felt inspected the baton which the magician was about to swallow, and which had previously passed from hand to hand between the spectators.

“Think about it, little ones!” said a soldier to the children, feigning a look of superstitious horror at the sight of the baton disappearing in the magician’s mouth. “Now this stick has one end resting on his stomach, and the other is tickling his brains.”

Suddenly the Arab turned to the missionary, smiling, and baring his teeth disgustingly.

“Where’s my nose?” he asked in a triumphant voice, and, without waiting for an answer, spread his hands, and said, “The Debil took ih!”

“Devil will take you too, if you don’t look out!” was the only words the formidable missionary could say. “The devil will take you too if you’re not careful.”

At the end of the performance, the Arab, instead of a baton, took several dozen eggs out of his mouth, clucking all the time like a hen, then swallowed them all and, having collected alms, left as skinny and withered as he had come.

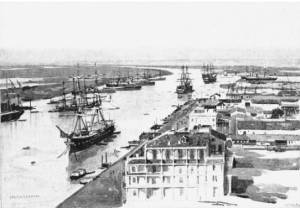

Entrance to the Suez Canal at Port Said. (Source: Loc.Gov)

Entrance to the Suez Canal at Port Said.[5]

The tea bell had long since rung, but the deck was still not empty. There was no end to the sellers’ positive response. They all squeezed into the dining room after us. (We discovered, later, that we were missing many things from the cabins.) The trumpet had already blared twice, announcing the departure of the steamer, and the motley crowd did not even think leaving with their goods, instead they fiercely chased the passengers. The steamer finally moved, slowly entering the Suez Canal, and only after dragging with us for about two miles did our tormentors begin to jump overboard into the boats, like a bunch of frightened frogs.[6]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Hunt, Ridgely. “Steamship Lines Of The World.” Scribner’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 3 (September 1891): 267-287.

[2] An instructional book on English to French translation from 1887 states: “To the French master of honorable descent, whose highest pride is his country, and only his second thoughts for himself, these outrages on the national character are the severest parts of his trials. But there are personal insults always impending over him, if not always actually outspoken, and which will, it is well known, lash him into a fury both impotent and ridiculous. If a well-worn allusion to snails and frogs as an article of food fails to produce the desired effect, the battle of Waterloo is re produced—that unfailing theme for ‘getting a rise out of Mossu.’” [Cassal, Charles. The Graduated Course of Translation from English Into French. Longmans, Green, And Co. London, England. (1887): 25.]

[3] On July 10, the Chusan arrived at Port Said, Egypt, a city which they explored early the next morning. [“Mail News.” The Dundee Advertiser. (Dundee, Scotland) July 7, 1890; “Mail And Steamship News.” The Glasgow Herald. (Glasgow, Scotland.) July 11, 1890.]

[4] Hunt, Ridgely. “Steamship Lines Of The World.” Scribner’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 3 (September 1891): 267-287.

[5] Hunt, Ridgely. “Steamship Lines Of The World.” Scribner’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 3 (September 1891): 267-287.

[6] Johnston, Vera. “Home From India.” Russian Review. (May 1891): 245-278.