MUHARRAM

Charles Johnston

September 4, 1889.

There was something peculiarly Indian about the circumstances which occasioned the flood. There was a young tiller of the soil of a thoughtful disposition, who owned three acres of land close by the embankment. In his ill-judged enthusiasm, it occurred to him how nice it would be to let a few inches of rich brown Ganges mud in upon his fields, so he cut a track across the embankment to get water for his brinjal patch. It was such a small track, yet within a few hours, the entire land was flooded. The consequence was that in a fortnight two million Bengalis were flooded out and homeless, and the whole district, and several others round it, were standing up to their waists in muddy water. The flood was checked at its source, and presently abated.

“I hate India,” said Verochka, disconsolately; a sentiment not without an echo in my own heart.

The rains had driven some of the intolerable heat out of the air, and ceasing for a few hours, had left the warm world full of freshness under a superb curtain of gray cloud. We were seated, Verochka and I, before the first bungalow of a barrack-like row, separated by a red road from the tree fringed square. Our cane arm-chairs stood on a square island of concrete, amid the soaking grass. We were waiting, already helmeted, for the carriage and for Eugène.

The air was full of the gurgling of minas, guzzling water-logged worms on the vividly green grass, and chattering like school-girls.

Over Eugène’s white barrack stood a patriarchal mango tree, about whose green glossy dome white egrets congregated. Above the shiny green of the leafage those white birds carried on their mystic dance. Lance-beaked and long-legged, they rose, with curved white wings and snowy plumes, poising like blown petals in the air, or setting forth, a silvery line against the gray, or circling in the air and settling back again with wings curved upward amid the green: taking all these lovely poses that enthralled the artist of Japan, until, to liberate his soul, he took brush and made every delicate line of them immortal.

“I hate India!” cried Verochka despairingly; and then, on a sudden, took on a more cheerful air; for round the bend of the road appeared a big, high-swung victoria from the Nawab Bahadur’s stables, bearing down on us with a fine clatter of hoofs. At the same moment, across the corner of the square, came Eugène. In a light suit, as befitted these hot-house days, under a helmet of white sola pith, he came over to us, pensive as always, and made his morning compliments to Verochka.

“Bonjour, madame! et comment ça va ce matin?”

Cheered by the gentle gray courtesy of Eugène, the lady responded hopefully and began to hate India a little less, preening herself for the drive in the big victoria now drawing up beside us on the road : a magnificent pair of “Walers,” the Punjabi coachman splendid in silver and crimson, and two gorgeous though bare footed grooms, also from the up-country, their button-shaped turbans barred with silver.

The grooms hopped down from back of the carriage, swung the open with many salaams, and us to our seats, Verochka and Eugène having the place of honor while I sat facing them, with the bronze-image countenances of the grooms looking down at him. With a swing and clatter of hoofs were off. Our dashing equipage had whirled us past the club, now quite deserted, in a meadow rank with “thief thorn” grass, which fastens itself abominably in one’s socks and trouser legs—the club where Eugène and I each afternoon of the rains played melancholy billiards, sipping weak beverages flavored with quinine and gin; past the Chota Lal Dighi, which is the lesser Scarlet Tank, with its mirrored date-palms and pearl-bedewed gossamers; past the Maidan; and so on, to a cross-road near a pond bedecked with blue and red water lilies, where amid shadowy Indian trees, stood the barred house of a Raja, who, being out of favor with the world, one day incontinently hanged himself, and who still flitted there, a disconsolate wraith.

Berhampore, Ruins Of Palace.[1]

I have a posthumous grudge against that Raja. I cannot for the life of me see why a love-lorn Raja of Ind should not be at liberty, if so minded, to hang himself and have a ghost. Yet I never drove past that lugubrious abode but I had to hear the tale of the up-hanging Raja—the narrator truculently counting on a horror I did not feel. If the Raja had a mind to hang himself, why, then, be hanged to him, and there’s an end. But perhaps that is only the effect of Indian heat upon the nerves.

The Nawab received us with that perfect simplicity and kindness which make him the most admirable or princes. We found ourselves thinking of the wide halls in the basement of the palace, where hundreds of poor people, refugees from the flood, gathered here to receive the food which the of prince distributed daily, in splendid generosity, making his Mohammedan co-religionists, and the Hindus, whom his faith damns as idolaters, equal recipients of his bounty. They were so crowded here, in spite of all the Nawab’s careful supervision, that it was as likely as not that we would have a cholera epidemic, and in a few weeks, when they separated again, would carry it about to the four corners of the district. After a few compliments, handed us over to one of his brothers, who was to take who was to take us in hand, and show us the festival. (It may be added that his younger brother plays an astonishing game of billiards.) From the palace itself, we could see nothing, so he piloted us through the quaint oriental street, with their coconut palm eyelashes, through the palace gardens, to a house with veranda overlooking the main street.

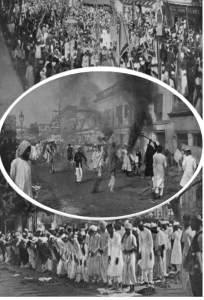

(Upper picture) Husain’s horse being led in procession through the Streets on the fifth of Muhrram.

(Center picture) The Marriage of Cossim. Torchlight Procession on the seventh of Muharram.

(Lower picture) Prayers at the Mosque on the tenth of Muharram after celebration.[2]

The road was thronged with white robed Moslems, men of very moderate possessions for the most part. They were full of the zeal of a faith that knows no hypocrites; where all men are ready to pray on the marketplace at noon, without shame or fear of ridicule. Already a murmur was rising from the throng that filled the streets, and one could feel the throbbing excitement of the crowd of mourners. A crowd was rapidly gathering. Mahommedans all of them, but many lands and many colors. The bulk of them were dark Bengalis, with white cotton garments and turbans, and there were a few up-country natives from Delhi and Agra and the old Mogul cities, who had come to trade, like the merchants in the Arabian Nights; and there also Persians and Afghanis, from beyond the frontier. They were beginning to grow excited, as all oriental crowds do at a religious procession, and their voices rose shrill and high from the street as they streamed past us. They pushed restlessly hither and thither, from one side of the street to the other. All were looking for the coming procession. The balconies of the houses opposite were full of eyes. Then, from the sunlit distance, where the street turned off, came voices in a wild and mournful chant, first inarticulate, then breaking into wailing words: “Shah Hassan! Vai Hussein! Shah Hassan! Vai Hussein!” The faithful were mourning for the sons of Fatima and Ali. The narrow streets echoed with their cries till the sound rose in waves, spreading over the flat roped houses and melting away among the palm trees: “Oh, Prince Hassan! Woe for Hussein!”

Our good guide, the Nawab’s brother, filled in the time while the procession was coming with a story of its origin and meaning, and a wonderfully stirring and pathetic story it was.

The place of history on which the Moharram festival rests was enacted on the banks of the Euphrates, in the middle of the seventh century. Its cause was Muhammed’s omission to appoint a successor to his power. Muhammed had no sons; his only daughter was married to his cousin Ali, and had two sons—Hassan, who died young, and Hussein, whom his Shia followers speak of as the Imam.

Ali and his children had every right to the throne of the Caliph; but Muawiya, one of the grandsons of Abu Bakr, the father-in-law of the prophet Muhammed, seized the Caliphate when Ali was slain, as he knelt at prayer. Hassan was persuaded to relinquish his rights of inheritance, but Hussein, Muhammed’s younger grandson, was braver and more ambitious. He took advantage of a popular uprising in his favor, and collecting a little band of seventy-two followers, fled from Medina to Mesopotamia. The inhabitants of Kufa, the capital of Mesopotamia and Syria, invited him to reign in their city, as they were weary of the weak and unjust rule of their Caliph Yazid, the son of Muawiya. Yazid was panic-stricken, and would have given up without a struggle, but for the interposition of one of his father’s most trusted advisors. With an army of several thousand he went to meet Hussein, surrounded his little band and cut him off from the river Euphrates, so the soldiers of the faithful Imam and his wife and children died of thirst. And the first ten days of the Moharram festival are celebrated in memory of the days when the followers of Muhammed’s grandson were dying of thirst in the Mesopotamian desert.

While our friend, the Mohammaedan Prince, was relating this the crowd had gradually been growing thicker, and every now and then there arose a plaintive cry: “Shah Hussein, Vai Hussein”—“King Hussein, Woe for Hussein!” For, though I have spoken of the Moharram as a festival, it is really a funeral procession, in which effigies of the tomb of Hussein are carries to one of the mosques outside the city. Three camels were led past, their saddles empty; part of the fallen caravan of the son of Ali. Their great awkward feet and legs spreading in the dust, to recall the passage of Hussein through the Mesopotamian desert. Then other mourners beating their breasts in a passion of despair and raising their sad cry. In Persia they gash themselves with knives till their fore heads are furrowed with wounds and the blood streams over their white tunics. For local color a series of tazias, that is, effigies of Hussein’s tomb, mounted in bullock carts, and slowly making their way past us, in the midst of the swaying, excited crowd, with its plaintive echoing cry: “Shah Hussein, Vai Hussein!” that rose sad, wild, and fierce, under the eastern sky.

The tombs passed, carried like litters by faithful Muslims; light wooden frames of colored silk, shaped like a sarcophagus, and adorned with tinsel and strips of colored mica. A certain gaudiness, without the least vulgarity—a combination that only the East can produce. Every prominent Mohammedan in the city had a tazia in the procession, the first being sent by the by Gaddanashin Begum, the grandmother of the Nawab, a great lady, who, in her secluded harem, still remembered the days when the royalty of her house was something more than a name. The grandmother’s tazia was crimson, with silver tinsel, and was something like a long, low tent in space, though not too big to find a place in a bullock wagon.

After it went a group of mourners, Mohammedan zealots, beating their breasts and raising that that plaintive cry: “Shah Hussein, Vai Hussein!” The blows resounded on their lean chests; their eyes were turned inwards in a fanatical ecstasy, and there was a wild savagery in their cries that well recalled the nomads’ wailing for their beloved Hussein, fallen on the field of Kerbela. Islam too has its tale of heart broken sorrow. Kerbela is their Gethsemane. In long file they passed, and the crowd surged forward beside them, and the mourners beat their breasts, raising their lament, pathetic as when it first echoed across the Euphrates twelve centuries ago: “Oh, Prince Hassan! Woe for Hussein!” Other tazia moved past, white, or variously colored, and then more camels closed up the procession, and the wailing cry of the mourners and the dull blows of their hands upon their breasts grew fainter in the distance.

There was nothing very splendid or striking about the procession of passionate mourners; but there was something almost terrifying, in the sight of that wild and ecstatic Mohammedan fanaticism which had carried the conquering hordes again and again across the plains of Eastern Europe, up to the walls of Moscow, Warsaw and Vienna, devastating and laying waste with relentless fury. The funeral procession was slowly winding its way along the dust covered roads to Amaniganj mosque. It was with something of relief that we saw the cortège at last disappear, as when the curtain falls on a too poignant tragedy.

We all began to talk rather excitedly, from sheer reaction of the nerves. It was a question of what we should do next. There were to be certain spectacular games whither the procession was wending, but it was doubtful if the direct road was open for carriages. We let the crowds get well on their way and then followed them in a carriage, taking a short cut as we thought, through a level tract, which was partly occupied by rice fields and partly by wild jungle and marsh. That short cut was fatal for we were suddenly stopped by a deep chasm across the road, which the floods from the Bhagirathi river had cut in their course, and it was impossible to drive across it.

The chasm was only two or three feet wide, quite impassable for the carriages, but easily crossed on foot; so several of us got out and walked, leaving the carriage, with the ladies, to go back through the city and follow the road taken by the procession. Our way lay through a half-dry marsh, along the narrow road raised like an embankment, with white mists hanging about it, and a rank smell of rotting weeds—the sort of place that matches a tiger’s coat. After a quarter hour’s roasting, to the sound of shrilling kites, we sighted the crowd under at Amaniganj mosque, under a huge banyan that would have shaded an army.[3]

The procession had arrived. Slowly and sadly, as befitted a funeral cortege, the tazias were brought and deposited in Amaniganj. The old mosque, gray with an atmosphere of decay, was stucco outside. It was quite bare save for the sacred banners of faded silk, with gorgeous silver gold-embroidered texts from the Qur’an in praise of the greatness and mercy of Allah. After the idol-crowded temples of the Hindus and the Jainas there is something austere and majestic, in these Mohammedan mosques. Absolutely bare, without an altar or an image, without a pulpit or a pew, nothing could be plainer; but there is a great beauty in the arched doorways and windows, with their Moorish tracery like lace fringes, and the texts from the Qur’an above the arches in Arabic letters lend themselves inimitably to the purposes of design. In this mosque there was a central well, round which the tazias were set down, under the shadow of the embroidered standards.

The crowd looked languid and drowsy, after too strong emotions, and then one of them would wearily strike his breast, cry, “Shah Hassan! Vai Hussein,” and then relapse into somnolence.

After a while they pulled themselves together and the games began. First came Persian fencers—dark sinewy fellows in waist cloths and turbans, their bodies like bronze images, their eyes glaring. The crowd watched them lying about on the grass, and the banyan tree spread its arms over us, in benediction. They fenced with long Damascus blades, basket hilted; it was all cut and slash, and take care you don’t hurt the other fellow, not wrist play with the point. And there was much up curving of the left arm, swift stepping back and forward, saluting and brandishing, which would look very pretty on the red field of war. Two or three couples made believe to hack each other to pieces, and glared furiously. [4] Eugène enjoyed himself consumedly, uttering little cries at every blow: “Good hit! Give it to him! Hit him again! Now he has him! No he hasn’t! Yes, he has! Good again! Ah!” For him it was Ronces Valles and the Cid.

Then something quite novel, to me at least; two fencers with two swords each, one in either hand. They must have practiced for months to have escaped killing each other. The slashing and interweaving of their clashing blades, four swords going all at once, was rhythmic as the falling of flails, and not a scratch to anyone. Then a further marvel, which I would have disbelieved if Eugène had told me of it: a fencer with four swords, mincing an imaginary foe. His leanings and brandishings passed belief, and the glaring of his eyes would have caused terror to the foe, while his weapons spread dismay among his friends. One would like such a man to desert to the enemy.

To him succeeded another with six blades, three in each herculean fist, like monstrous tridents. And how that man contrived to last a full five minutes, slashing and dashing and clashing, prancing, and lancing, and dancing, I shall never know. He came forth unharmed from what looked like a porcupine of bristling blades. If there was a fighter like that on my side, I should desert. I felt like deserting then. Whether the man with six swords was excelled, is a point on which I am not able to give evidence. The heat and the vapors from the marsh we had passed through got the better of me.

The carriage having meanwhile arrived by the long way, we went for a drive behind another fine pair of “Walers.” His Highness and the lady occupying the places of honor, while Eugène and I sat facing them. The city had once nearly a quarter of a million inhabitants, yet you can drive through it, from end to end almost, without seeing any city at all. So swathed is it all in gardens, mango groves, and palm-fringed avenues, that it looks more like a greenhouse than a city.

The Great Gun At Topkhana.[5]

We saw one of the cannons Clive fought with at Plassey nearly a century and a half ago. The armies of India were utterly defeated there, yet the subject is not a sore one with His Highness. Quite the contrary. His family owe their rank to England’s victory. When Clive made away with that particular rascal, Siraj ud-Daulah, and the old Nawabs, the present house was set upon the throne, as a certain and loyal mainstay of the white rulers at Calcutta. So he showed us the Plassey cannon with a smile of complacent satisfaction. The gun had climbed half way up the stem of a banyan tree; caught in a fork when the tree was young, it had risen in the world with it. I once saw a huge millstone in the same predicament, but cannot remember where. I think it was in Scotland or Russia, but may be thinking of Mons Meg and the King Cannon at Moscow.

The carriage stopped. The Nawab asked us all to alight. He led us through a lofty archway into a wide courtyard where grass grew thick among the tiles. Across the courtyard rose the great red mosque of Murshid Quli Khan, with five huge domes of red brick in a row. There was something solemn and mournful about the great red building, left lonely there in the sweltering sunlight, overgrown with grasses and weeds, and haunted by owls and bats. Snakes and lizards lurked where the worshipers once knelt. The burning rays beat down upon it, and the wild tropical rain storms, and one day they will take possession and grind it all to impalpable dust. But it is still a splendid ruin, and under the threshold lies the man who built it.

Murshid Quli Khan, founder of Murshidabad, the capital of Bengal in Mogul days, was a renegade Brahman, and in this the prototype of millions.[6] He deserted thirty three crores of gods for the one Allah when the Moguls reigned in Delhi. Born of a thousand generations of priests, he was a fierce and bloodthirsty warrior, who crushed his province with a hand of iron. And now he lies beneath the gateway of the mosque, humble in death. Yet the vow of his humility is not fulfilled, for though his head is prostrate in the earth, the feet of the faithful pass no longer over it. His once great capital is a drowsy village, his world famed mosque a grass grown ruin.

Evening was coming, Gold and purple banners decked the sky beyond the river. The flowing colors of the sun set flushed across the quiet waves. The gloom of night gathered round us. Crickets began their whirring song, in the grass from the tree stems, among the leaves, till all the air throbbed and rippled and whispered with their music. We passed by a mosque where a famous preacher from Bagdad was holding forth; a dark, proud face, under a green turban that told of a visit to Mecca. The deep, ringing tones of the Haji’s voice, the nervous gestures of his hands, his eyes flashing in the torch light, all spoke of power of a living faith, a sense of divine destinies, a sacred message to the world. The good gray prince heard him with reverence to the end, and one could see how his heart thrilled responsive to the summons of the prophet.[7]

~

The sun, and I suppose, the poisoning of my body by mosquito-bites, laid me low, two days after Muharram, with a violent and prolonged attack of jungle fever.[8] During that first fever spell, in August and the beginning of September, I was completely bowled over a week or ten days. It begins with a deadly languor and weariness, which drives one to lie down; this passes into a miserable, icy chill which shivers through one’s body and bones, and even heaps of blankets are helpless to combat it. And there is, withal, a weariness of mind and spirit that turns the whole world gray, leaving one without faith, hope, or grace, wisdom or understanding.

Then comes a change of miseries. One’s heart, which has threatened to come altogether to a standstill, gradually quickens its beats, and is presently pounding away like those trip-hammers which Don Quixote and Sancho heard in the darkness of the forest. This pounding keeps up, in hot, dry misery, till one feels as though the heart would come bodily through one’s ribs and burst at the next stroke. Yet there are lulls when one is of happy quietness, when one is filled with divine peace.

At last the furnace-heat in one’s blood is tempered by profuse perspiration which leaves one a half-dead rag, faint and breathless, seeking only the unconsciousness of sleep. And this recurrent purgatory goes on together. For days one is never secure. It always lies in wait, hiding in one’s veins, ready to break forth again.[9]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Furneaux, J. H. Glimpses Of India. Historical Publishing Company. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1895): 71.

[2] “Ya Ali! Ai Hasan, Ai Hasan, Ai Hasan, Ai Husain Shah!” The Sphere. (London, England.) January 18, 1913.

[3] In “Holy Man,” Johnston writes: “After the procession, I went on foot through recently inundated ground, to see some Moslem games.” [Johnston, Charles. “A Holy Man: Helping to Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 110, No. 5. (November 1912): 653-659.]

[4] In “Mussulman Festival,” Johnston writes: “Then outside the mosque, under the shadow of the gigantic banyan tree, came another part of the celebration—an exhibition of Oriental fencing and swordsmanship. The swords were splendid beyond comparison; great Damascus blades, with wide hilts of jade or agate, or chased with silver and set with turquoises and precious stones. And the costumes of the fencers were also splendid; all kinds of gaudy colors, which yet looked harmonious under the glowing Indian sky. But of the fencing itself less could be said. It seemed to me that it would be far more dangerous to your friends than your enemies, there was so much leaping and brandishing and waving the shining blade […] Then came a fencer with a sword in each hand, and the way he twined and twisted the two blades around his head and cut figures of eight with them through the air, was truly marvelous; something like an Indian club performance with swords, but ever so much swifter in the movements. The air simply hissed and swished with the passage of the blades, and they never once even grazed each other. But a greater wonder was in store. The fencer with two swords was followed by another with four, two in each hand, held hilt to hilt, so that they stuck out at right angles, to his arms, as the cross stroke of the letter T does. And these four swords he whirled and twisted round his head so rapidly that you simply could not follow them, and they made bright streaks and circles in the sunlight, as when one whirls a stick burning at the end. And all this without cutting his own head off; a sufficiently marvelous performance. But even this miracle was destined to be outdone—by a swordsman with six swords, three in each hand. He held four as before, two in each hand, at right angles to his outstretched arm; then a third in each hand, in the direction of his arm produced; so that with his arm, the three swords made a cross. This is difficult to describe, but I hope I have made the thing clear. At any rate, it does not greatly matter, for in a second or two it was impossible to tell what way he held the swords; you had the impression of the air being full of bristling blades, whirling about like lightning flashes, and that was all. In the midst of it stood the fencer, like Jove in the midst of his thunderbolts; and how it came that he was not terrified at his own performance, is something I have not since been able to understand. I would not have consented to stand in the midst of those six whirling blades for a full pension, or even for a month’s pay of the Nawab himself.” [Johnston, Charles. “Mussulman Festival.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) December 4, 1898.]

[5] Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud Of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis Of The History Of Murshidabad For The Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 172.

[6] Johnston writes: “The motive for conversion has been social rather than theological, a passionate escape from the compartmented oppression of the Hindu system of caste, which confers high privileges on the Brahmans and bears so harshly on the lower castes. So that there is no real race cleavage behind these sectarian feuds; it is a mental, not an ethnical discord. But this discord is sufficiently threatening to inspire in the minds of the native politicians, Hindu and Mohammedan alike.” [Johnston, Charles. “A Perspective On India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXXXVIII, No. 6. (December 1926): 848-856.]

[7] Johnston, Charles. “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897; Johnston, Charles. “Mussulman Festival.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) December 4, 1898; Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319; Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804; Johnston, Charles. “A Holy Man: Helping to Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 110, No. 5. (November 1912): 653-659.

[8] Johnston, Charles. “A Holy Man: Helping to Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 110, No. 5. (November 1912): 653-659.

[9] Johnston, Charles. “A Holy Man: Helping to Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 110, No. 5. (November 1912): 653-659.