Groundhog Day dates back to the Pagan celebration of Imbolc, and the Christian observance of Candlemas. Its lessons are still relevant today.

These days when you say, “Groundhog Day,” most people immediately think of the 1993 movie. Only after that do they remember the February 2 holiday featuring a cowardly rodent. Most have forgotten its origins with the Roman Catholic celebration of Candlemas. Even more are ignorant of its origins with the Celtic observance of Imbolc. Each of these iterations has something to teach those who are observant.

Christian Appropriation of Pagan Festivals

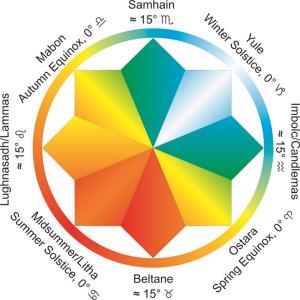

Pre-Christian Celts divided the year into eight equal portions, called “The Wheel of the Year.” The quarters fall at the summer solstice (Litha, on or around June 21), the winter solstice (Yule, on or around December 21), spring equinox (Ostara, on or around March 21), and fall equinox (Mabon, on or around September 21). The cross-quarters lie at the midpoints in each season. The midpoint of spring is Beltane, on or around May 1. The middle of summer is Lughnasadh, on or around August 1. Halfway through fall is Samhain, on or around November 1. The midpoint of winter is Imbolc, on or around February 1. (These dates are inverted for those who celebrate in the southern hemisphere.) Each of these quarters and cross-quarters represents a different phase in the agricultural year and carries with it a spiritual significance.

When Roman Catholicism entered the unchurched lands of Western Europe, it Christianized the indigenous festivals to facilitate the conversion of Pagans. Ostara was renamed Easter. Beltane was transformed into May Day with its fertility pole. Litha corresponds to the Roman Catholic Solemnity of the Birth of John the Baptist. Lughnasadh, the festival of first harvest, became Lammas, or the Loaf Mass. Mabon, the feast of the second harvest, became the Feast of Matthew the Apostle. The Church turned Samhain into All Saints’ Day. We are more familiar with the day before—All Hallows Eve, or Halloween. Christmas eclipsed Yule to such an extent that many think they are synonymous. And finally, Candlemas replaced Imbolc.

Imbolc

For ancient pre-Christians, and for Neopagans, Imbolc represents the turning point of winter. According to Dhruti Bhagat:

The word “imbolc” means “in the belly of the Mother,” because the seeds of spring are beginning to stir in the belly of Mother Earth. The term “oimelc” means ewe’s milk. Around this time of year, many herd animals give birth to their first offspring of the year, or are heavily pregnant. As a result, they are producing milk. This creation of life’s milk is a part of the symbolic hope for spring.

This holiday also celebrates Brigid, the Celtic fire and fertility goddess. Over the years, Brigid was adopted by Christianity as St. Brigid. Brigid (or Bridget) is the patron saint of Irish nuns, newborns, midwives, dairy maids, and cattle. The stories of St. Brigid and the goddess Brigid are very similar. Both are associated with milk, fire, the home, and babies.

Learning from Imbolc

Imbolc is a time of looking forward to a Spring that has not yet sprung. As such, it represents faith and hope. Seeds remain in the earth, not yet peeking through the soil. Lambs are still in the womb, not yet born. The darkest time of the year (Yule) has passed, but the coldest time of the year is upon us. It takes a special kind of hope to look forward to that which has not yet come. Imbolc is a time of receptivity, gathering, and waiting for fruition.

How do modern people celebrate Imbolc? The Green Parent recommends crafting a straw doll (Brideog) or Brigid Cross as the ancients did. Just as a nesting mother prepares her home for a new baby, spring cleaning prepares your life for fresh things. Like the waters of a mother’s womb nurture her young, you might consider a trip to a spring or well, to focus on the significance of holy waters in your life. As a Christian, you can celebrate these aspects of Imbolc—you don’t have to throw out the baby with the bathwater. From Imbolc, you can learn the practice of patiently waiting for your seeds of faith to grow.

Candlemas

Celebrated in Celtic lands, Imbolc paralleled the Roman festival of Lupercalia. To combat these two Pagan holidays, the Church created Candlemas. Imbolc focused on Brigid, who is associated with babies. So Candlemas highlighted the purification of Mary, after Jesus’ birth. This new holiday also recalled Mary and Joseph’s dedication of the infant Jesus in the Jewish temple. In Luke 2, Simeon recognizes the babe as the Messiah and prays:

“Master, now you are dismissing your servant in peace,

according to your word,

for my eyes have seen your salvation,

which you have prepared in the presence of all peoples,

a light for revelation to the gentiles

and for glory to your people Israel.”

Learning from Candlemas

As Jesus is recognized as a light of revelation, Candlemas features tapers and lights to banish the winter darkness. Traditionally, believers brought their candles to the church to be blessed. As with other winter festivals of lights such as Christmas, Hannukah, Kwanzaa, and Yule, Candlemas asserted the power of light over darkness. The sun itself, the greatest source of light, also became a prominent feature of Candlemas. Alementarium reports:

Pope Gelasius I is said to have given wafers or flatbread to pilgrims arriving in Rome. However, there are also other stories and superstitions. Round, golden pancakes served in February are evocative of the sun and may have been a symbol of fertility and prosperity. In order to obtain an abundant harvest, a farmer would traditionally flip the first pancake with his right hand while holding a gold coin in his left hand. The gold coin would then be wrapped inside the pancake and kept at the top of a wardrobe until the following year, to then be given to the first poor person encountered.

The lesson we draw from Candlemas is similar to Imbolc’s reminder: No matter how cold and dark life gets, the sun will always return. It will get brighter. It will get warmer. Life will resume.

Groundhog Day

The modern celebration of Groundhog Day evolved out of Pagan and Christian midwinter festivals. Stephen Winick writes about the German element that, added to Imbolc and Candlemas, created what we now call Groundhog Day:

Weather prognostication, then, became associated with the beginning of February during ancient times, and the tradition persists until today. But this still leaves us in the dark as to the groundhog and his role in the process!

It seems this part of the tradition, too, comes from Europe. Specifically, it comes from parts of Europe that were Celtic in ancient times, but were later inhabited by Germanic speakers. Germans believed the weather was predicted by a badger rather than a groundhog, but the traditions are otherwise almost identical… it was only natural for German-speaking immigrants to America to substitute the groundhog for the badger.

The first mention Yoder has found of groundhogs predicting the weather on February 2 is in a diary entry for that day in 1840, written by a Welsh-American storekeeper in Pennsylvania: “Today the Germans say the groundhog comes out of his winter quarters and if he sees his shadow he returns in and remains there 40 days.”

In the United States, Groundhog Day traditions continue to modern times. Winick reports that from as early as 1887, Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania has been a major center of Groundhog Day lore. Each year, Punxsutawney Phil emerges from his den to the amusement of onlookers both live and virtual. If he sees his shadow and goes back to bed, there will be six more weeks of winter. If he remains in the sunlight, spring will come early.

Learning from Groundhog Day

We moderns can take a lesson from Groundhog Day. Each of us has a shadow self, a dark part of our personality that we would rather keep hidden. This shadow part may be due to childhood trauma, mental illness, addiction, or other negative contributors. Medical News Today says:

Although the shadow self can include negative impulses, such as anger and resentment, [Carl] Jung believed that it also held the potential for positive impulses, such as creativity. He felt that the shadow self is integral to a person’s experience of the world and their relationships. He also thought that a person could gain a better understanding of themselves and become more balanced by working with their shadow self….

Jung did not view the shadow as a negative or shameful part of a person’s personality. To him, it was an important part of their psyche. The goal of shadow work is to assimilate the shadow and the persona so that a person can learn how to manage impulses they usually ignore, such as anger or greed.

Each of us has a choice as to how we will deal with our shadows. Like Punxsutawney Phil, we can turn away from our shadow, refuse to deal with it, and endure a longer psychological winter. Or we can cause our own inner spring to come early by looking into our shadow selves in the light of understanding. In a way, you might say this is what Bill Murray’s character does in the 1993 classic movie Groundhog Day. Forced to relive each day until he deals with his negativity and becomes a better person, Murray teaches us not to run from our shadows as the groundhog does, but to face them.

Christians & Pagan Holidays

Many followers of Jesus, upon learning about the Pagan origins of Christian holidays, abandon those Christian holidays altogether. Or they shun good traditions that originated in pre-Christian settings. I have known numerous Christians who refuse to put up Christmas trees or color eggs at Christmas because of their Pagan origins. This is a tragic practice of throwing out the baby with the bathwater. It’s far better for Christians to ask, “What can I learn from the Pagan roots of the holidays we love?” There’s nothing evil about these other religions. We might just find something of value if we take the time to listen.

Spirituality Like an Ice Cream Social

In my article, “How Neo paganismHas Made Me a Better Christian,”I write about how spirituality can be like an ice cream social:

…One of the things we liked to do in our Southern Baptist churches was enjoy ice cream socials together. We’d get together with our ice cream makers, churn our own homemade ice cream, and share recipes with folks. We’d taste each other’s ice cream and load it down with lots of toppings. And you know what? Nobody judged each other for the ice cream and toppings we put in our bowls. One person’s bowl might be different than mine, but it didn’t matter. Why? Because it was never about ice cream anyway—it was about the love that we shared as we feasted together.

Our relationships with people of other faiths should be like that. Rather than approaching people of different religions with an attitude that says, “Your bowl is full of the wrong stuff,” it would be so much better if we could say, “Here’s some of mine—can I try some of yours?” Spirituality like an ice cream social would mean enjoying the tastes and sharing the recipes we’ve discovered with one another. It would remind us that it isn’t about precepts and practices, but the propagation of love that God wants us to share.

This is the first of eight articles I will write in 2024, with the title, “Christians and Pagan Holidays.” Each will feature a Pagan holiday that Christianity adopted and synthesized into our own religion. Rather than shrinking away from Christian holidays when you learn about their Pagan origins, I hope you’ll press into them. You may just find that, like at an ice cream social, there are lots of great tastes to share.