Last year I wrote a piece titles “Where The Sandstone Yawns,” about the mysterious happenings of Custer’s Black Hills Expedition. One of the main “characters” of the (non-fiction) story was William Ludlow. This same William Ludlow that served as the basis for Jim Harrison’s fictional character of the same name in Legends Of The Fall. This, then, is a conclusion to Ludlow’s story, which , I think, is heroic and fascinating as fiction—Shawn.

William Ludlow was stationed at 1125 Girard Street in Philadelphia in the early 1880s to assist the river and harbor improvement projects. Ludlow’s thorough study of the district’s needs enabled comprehensive projects for the improvement of all the navigable waterways.[1] It was not so long after his expedition into the Black Hills. Ludlow would have talks with the leading scientific authorities. It was around this time that Ludlow showed interest in Theosophy. (Blavatsky herself once resided at 1111 Girard Street when she lived in America.)[2] Ludlow discussed Zoellner’s “Transcendental Physics” and the writings of Blavatsky with his friend, Major Otto E. Michaelis (an authority on practical chemistry and electricity, and a prominent member of the Engineers’ Club of New York City.)[3] For Ludlow, Theosophy explained (among other things,) “the history and nature of extinct civilizations and races unknown save by their relics, and the causes of their extinction: the unequal development of existing civilizations.”[4] Given his experience in the Black Hills, this must have weighed on his mind.

After the Civil War, J.P. Morgan’s Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), was eager to develop international trade using the Port of Philadelphia. Raw exports ( petrol, grain, and iron,) were found in excess in Pennsylvania, but there was no reliable steamship transportation to facilitate trade. Griscom, with the support of the PRR and Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, urged Philadelphia commercial interests to support mercantile development. In 1871 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania granted a charter to Griscom for the creation of the International Navigation Company (INC.) The primary financial backer, the PRR, would provide free wharfage and amenities. In 1872, Griscom and representatives of the PRR held a conference which resolved to establish a steamship line from Philadelphia to continental Europe. Antwerp was chosen as the European terminus—a once bustling port, by the 1870s excessive silting had prevented any steamer from accessing the harbor. With new dredging technology designed by engineers like Ludlow, a solution had presented itself. The decade of 1873-1883 brought many advances for the INC. The sizes of their ships doubled, and the number of their passengers increased tenfold. Consolidated transatlantic and transcontinental services provided by the INC and the PRR proved popular with European immigrants, for a single ticket could carry a passenger from Central Europe to Chicago.[5]

In Philadelphia, Ludlow quickly earned a reputation for his integrity.[6] His work cleaning the Schuylkill River was particularly lauded.[7] “The field of micro-biology in connection with water supply is as yet hardly entered upon,” said Ludlow, “but its application cannot fail to prove of the very highest value and furnish indications beyond the possibilities of other methods.”[8] But he was still a soldier. In August 1885, he was a part of President Grant’s funeral procession in New York as part of General Hancock’s First Division.[9]

The effect of Ludlow’s work soon became known to the citizens of Philadelphia, and he worked with and among the “honored names of the modern ‘knights of industry.’”[10] Ludlow even took his daughter Genevieve (Acton’s mother) with him “to visit his friend J.P. Morgan.” (A fond memory that Genevieve would never forget.)[11] Ludlow, being a fixture of Philadelphia high society, attended “notable receptions” with men such as Morgan and Griscom—the latter’s son, also named Clement, was being groomed for business at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Finance.[12] “Clem,” as he was known, was a young athletic man who, incidentally, developed an interest in Theosophy around the same time as Ludlow. Ludlow took a liking to Clem, and so did his daughter. In November 1888 Genevieve and Clem were engaged.[13] Ludlow, meanwhile, was sent to Michigan as Chief Engineer of the Fourth Lighthouse District.[14] He returned to New York the following year for his daughter’s wedding. Genevieve looked charming in a white silk robe, which was almost entirely covered with a rich veil of old point lace, and caught with a single spray of orange blossoms. Col. Ludlow, who wore full regimentals, gave his daughter away. Rev. E.H.C. Goodwin, chaplain of Governor’s Island, performed the ceremony. The guests were mostly from Philadelphia, where Clem’s family resided. There were also a fair number of soldiers from Governor’s Island. The most famous guest, however, was undoubtedly General William Tecumseh Sherman. After the wedding, an elaborate breakfast was served to 60 guests in the banquet hall of The Brunswick.[15] It was probably at this time when Ludlow met W.Q. Judge, President of the New York Branch of the Theosophical Society, and General Secretary of the American Section. Judge was like a “submerged continent, revealing its lofty peaks as but islands jutting from the surface of the sea,” Ludlow would say. “But in the perspective of time, the sea subsides, and we see the height of those towering mountain ranges of attainment, the far expanse and fertile planes of his human sympathy. We need distance to see mountains; we can delimit continents only on a world-wide map.”[16]

Weeks after their marriage, both Ludlow and Genevieve joined Clem in the Theosophical Society.[17] (Ludlow’s sister, Louise Nicoll Ludlow, would join in 1891.)[18] Beginning in December 1891, Ludlow would pen a series of articles on Theosophical cosmology for The Detroit Free Press.[19] (The series ran through January 1892.) In the summer of 1892, Ludlow was relieved from duty, as he went outside the chain of command when making improvements on lighthouse safety.[20] Upon investigation, it was found that Ludlow acted in the right, as there was evidently something going on behind the scenes. In March 1893 he was re-instated.[21] At the end of that year he was made part of the military attaché for Thomas Bayard, America’s first Ambassador, who was sent to London in 1893. In December 1893, Ludlow left Detroit for New York.[22]

(Left) Genevieve Sprigg Ludlow.[23] (Right) Queen Victoria c. 1893.

On January 3, 1894, Ludlow departed for London on Griscom’s City Of New York on her first launch from the INC’s new pier at the foot of Fulton Street.[24] At the American legation there was Thomas Bayard, America’s first Ambassador (who had recently accepted the post in 1893.) His private secretary was Lloyd C. Griscom, Clem’s brother, and an in-law of Ludlow’s. There was also James “Rosy” Roosevelt, who succeeded Henry White as Secretary of the Embassy in London in late October 1893. He was the cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, and older half-brother of Franklin D. Roosevelt. His post was a source of commotion in the American colony in London, as it was claimed that he received his post after a $10,000 dollar donation to the Cleveland campaign.[25] Not long after his arrival in London. tragedy struck. James’s wife, Helen Schermerhorn Roosevelt (the daughter of the late William Astor) died on November 12, 1893.[26] His cousin, Anna Roosevelt (Theodore’s older sister,) came over to help take care of James’s half-grown children, and to act as his hostess.[27] Both Anna Roosevelt and Ludlow’s wife, Evie Ludlow, were presented to Queen Victoria on the same day, February 27, 1894.[28] (This did not mean there was not a healthy display of competition, Bayard, Ludlow, and Roosevelt were among the committee responsible for overseeing the “friendly” cricket match in July 1894.)[29] One of the more notable events among the Legations at this time was happened at the end of the year. On November 6, 1894, Ludlow and the American Legation attended the Memorial Service of Tsar Alexander III, along with the Duke of Connaught and other Diplomats. Reverend Eugene Smirnov , Blavatsky’s friend, performed the rites.[30] While touring Europe, Ludlow made the following observation regarding the potentiality of war:

The nineteenth century has been one of unprecedented intellectual and material development, and its close marks the highest level thus far attained by mankind in physical and mental domination. Its most striking phase, perhaps, is the remarkable condition of military preparation in which stand the ruling nations of the world. Europe, which represents the epitome of modern civilization, is practically an armed camp, and its several hosts stand silent in readiness for the trumpet call, with nerve and sinew strained to meet the shock of international conflict.[31]

From May until July 1895 he was in Nicaragua, to report on the feasibility of a Nicaragua Canal.[32] “Chimera are long lived, and their pursuit will continue to be a fruitful source of discovery while man has ideals and the will to realize them,” Ludlow writes. “The dream of a direct westward passage for ships from Europe to Asia led Columbus, four centuries ago, to the shores of a new continent, and the problem still engages the interest and attention of the world.”[33]

St. George, Staten Island.

He returned to New York in April 1896, not long after the death of William Quan Judge, and the reformation of the American Theosophical Society. Stationed at the Lighthouse Depot in Staten Island, Ludlow created the borough’s first Theosophical Society Branch, the St. George T.S., of which he was President.[34] “He had scoured Staten Island on a bicycle, when he had his headquarters there, to find and gather together scattered students of Theosophy, who could meet as a Branch, in his home on Thursday evenings.”[35] One member would later recall:

I knew the General and had some experience with another set of his “precepts”—those he had laid down for the engineers in his drafting room. When I first went there I saw a number of signs on the walls, reminding me of the mottoes that used to be worked in worsted, and which one still sees, occasionally, in old-fashioned rooms in the country; only these were lettered on boards. They struck me as rather quaint, in an army post. Over my own table the legend read, “A Place for Everything, and Everything in its Place” a copy-book maxim, if there ever was one. It did not seem a particularly novel sentiment, until, a day or two after I had started work, I found the General beside me, asking me what I thought it meant and why it had been put there. I did not tell him—as I would have anyone else, had I told the truth—that I had thought it a blend between a pious hope, and a counsel of perfection. I do not think I told him anything at all. But I can remember still how hot my face felt, as I started. [Ludlow] was not concerned with phrases, but with facts. A principle, for him, was not a theory nor an abstraction; it was a compelling law of action. If a thing was the right thing to be done, it was to be done. That was all there was to it. And I believe it was in large measure the very simplicity of his attitude here, which made him the leader that he was. It was as though the completeness of obedience which he himself rendered to his principles, so filled and flooded his will with them, that when that will was directed toward you, you felt it as a kind of cosmic force—a compulsion of necessity, which it never occurred to you could be resisted or denied. Something like this must, I think, be the secret of all true leadership, all real command. Its power must be gained by obedience. It cannot originate in the commander, but can only be transmitted by him, its authority and compulsion descending through him from a higher source. [36]

A war with Spain seemed inevitable. News from General Calixto Garcia, commander of the patriot forces in Eastern Cuba, sent letters to America petitioning for help. General Jose Maceo, of the First Army Corps, was killed July 5th in an encounter at Lama del Gate. This engagement was a bloody one. The patriots occupied a very strong position on Gato Hill, and were attacked by the Spaniards under General Vara del Rey. After the long engagement of more than eight hours, however, and the Spaniards were compelled to retreat.[37] As the weeks went on, the stories from Cuba told of a resistance force who were still in the fight, but needed American assistance. In Havana the column of General Vara Del Rey, 2,000 men strong, was defeated and dispersed by the Cuban resistance under General Calixto Garcia. More than 1,000 Spaniards were left dead on the Estate Costomido; the remaining part of the column entered Manzanillo in disarray. The battle turned against the Spaniards when General Del Rey tried to cross the River Buey en route to Manzanillo. Ambushed, the Spaniards faced heavy fire from Cuban rifles and cannons. During the resultant confusion, they were unable to reply to the volleys of their foes. Vara Del Rey only escaped capture when a young Spanish captain by the name of Quintero, along with a hundred men, staved off Garcia’s cavalry attack.[38]

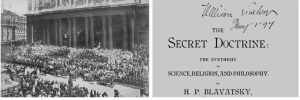

(Left.) Diamond Jubilee. (Right) William Ludlow’s copy of The Secret Doctrine at Harvard Library.

That summer Colonel Ludlow returned to London, where he represented the Americans in the parade of military attachés during Queen Victoria’s Jubilee.[39] (The annotation in Ludlow’s copy of The Secret Doctrine suggest he was reading that book at the time.) When he returned to the United States, fissures in the Theosophical Society were beginning to show. By February of 1898 the Society would split. Clem would lead a faction that was based in New York, and Ludlow would be among the Executive Committee. His presence, however, would be minimal. On February 15, 1898, the U.S.S. Maine exploded in Havana Harbor. “The people of New York and Brooklyn, need lose no sleep through fear of any danger from warships,” said Colonel Ludlow. “The land fortifications around New York, without taking into consideration our navy would be ample protection against any fleet that might be sent against us.”[40] On March 27, President William McKinley demanded that Spain give up Cuba, and concede Cuban independence. Spain did not like this idea, and instead declared war on the United States. The following day, the United States declared war on Spain, and prepared its navy for a fight in Cuba and the Philippines. On May 1, 1898, Admiral George Dewey won a decisive victory against the Spanish Fleet at the Battle of Manilla. The next battle would be in Cuba, in July 1898. Ludlow, who was made a General, would lead a made General Ludlow, and would lead a Brigade to capture San Juan Hill. Theodore Roosevelt, leading his own “Rough Riders,” would also join the fight.

~

General Calixto Garcia stood on a hillside overlooking the sea at midday on June 22nd 1898. A smile appeared, though hidden beneath his coarse mustache, when he saw the curl of black smoke on the horizon. “Los Americanos finalmente han llegado,” thought Garcia, with a feeling of relief. Before him, stretching eight miles across Santiago Bay, was a single-file parade of ships, the American invasion fleet. Packed on the decks of the troopships were cheering soldiers who waved their hats and flags. Admiral Sampson, steaming past the Spanish forts, boomed a salute from the guns of his flagship, the New York, and circled out to sea to drop anchor.

(Left) Going ashore at Aserraderos.[41] (Right) “General Ludlow and General Garcia.”[42]

General Garcia’s rebel army began to cheer in their hidden mountain encampment. For three years they had been fighting a guerrilla-war of independence against the Spaniards. They were malnourished, poorly-clothed, blistered, and battle-hardened. Assistance from their Yankee brothers was very much welcomed. The Americans on board General Shafter’s headquarter-ship, Seguranca, steamed to Aserraderos and anchored in a nearby cove. Admiral Sampson, General Shaffer, and General Ludlow, accompanied by a guard of soldiers, made their way to the Cuban shore on board a few small boats. General Garcia and his guard greeted the American officers at the beach with all military honors; horses were given to the American officers who were escorted up a steep trail which led to General Garcia’s headquarters—a shabby hut, covered with leaves. For several hours the Cuban commander explained his plans to the Americans. General Garcia had trapped the Spanish General, Luis Manuel de Pando, in Manzanillo effectively severing any communication with the other Spanish forces stationed in Santiago. General Garcia then placed a map before the Americans which revealed all the mountain trails leading to Santiago from the most convenient landing spots of Cuban harbors. Ludlow studied the map with great interest. “General Garcia,” said General Ludlow, “I will need all the information available regarding the most feasible plans for transporting a large body of troops overland.”[43]

On the afternoon of June 30th, the Spaniards noticed a balloon ascending about a quarter of an hour. After its descent they saw the enemy pick up their tents and move their camp, but as the night fell, they were unable to locate their new position, though they guessed it pretty accurately.[44] The Spanish requested reinforcements, but reinforcements never came. The 514 men under General Vara del Rey’s command, 67 regulars armed with Mausers and 47 guerrillas with Remington rifles, were the only troops left to defend El Caney.[45]

Generals Garcia, Lawton, Ludlow, and Chaffee inspecting the lines at El Caney.[46]

At 6.35 a. m. Captain Capron, on a hill 2,375 yards from the stone fort, opened the attack with a shell fired at a body of Spaniards who were falling back to the trenches. Another shot went through the roof of the stone fort. The infantry was then distributed. Chaffee’s brigade (the Seventh, Twelfth, and Seventeenth Regiments) advanced on El Caney from the east. Colonel Miles’s brigade (the First, Fourth and Twenty-fifth Regiments) attacked from the south. Genera; Ludlow’s brigade (the Second Massachusetts Volunteers, and the Eighth, and Twenty-second Regulars,) was sent around to make an approach from the southwest.

General Chaffee rode up and down behind his firing line encouraging his men. “Now, boys, do something for your country today,” he frequently said. Chaffee did not think the Spaniards would hold out very long. General Ludlow’s men made slow but steady progress through a tract of woods, running from bush to bush and shooting at a Spaniard whenever they saw one. The Second Massachusetts Volunteers behaved splendidly, exposing themselves freely, and displaying fine marksmanship. Miles’ brigade made up a good deal of ground to get well into the fight, but it came up in time to take its share of the assault when the Second Massachusetts and the Twenty-second Regulars were lying in the road for a breathing spell. The Fourth and Twenty-fifth of Miles’ brigade were fairly fresh, and they moved up on the blockhouse northwest of the town.[47]

A faint blue haze curled up from the summit of the hill just below the blockhouse.[48] There was a sputtering of rifles near Chaffee’s brigade as it moved toward the Santiago road. To the left, where Ludlow was, the sputtering was more fierce. There was a continuous, nervous ripple of discharges, extending across the entire front of their line. The Twelfth and Twenty-fifth were almost deprived of their officers by snipers in the rush. The Second Massachusetts struggled into the line of assault, and Lieutenant Field was instantly killed. Lieutenant-Colonel Patterson of the Twenty second was badly wounded, and had to be sent to the rear—but there was no wavering among his men.

A Blockhouse and defense line at El Caney.[49]

General Ludlow, with his white sailor cap firmly on the back of his head, galloped his horse to the front. His horse was killed under him. “C’mon boys!” he shouted, scrambling to his feet. He pushed forward on foot, gloriously swinging his little hat in his hand, while continuing to beckon his men to follow.[50]

“The buggers are hidden behind rocks, in weeds, in the underbrush,” one of Ludlow’s men lamented. “We can’t see them, and they are shooting us to pieces.”

With nothing to protect them from the deluge of Spanish bullets raining down on them from the fort on El Caney, Ludlow’s men scrambled for cover. They were forced to burrow into the soil, or crouch behind trees.[51] Sixty light–blue-clad men stood in a trench with a line bent in the middle at right angles by the square turning of the ditch. At the bend of the line, some blue-jacketed young officer would stand, exposed to the belt, or feet, rising at the word of his officer’s command. This went on for hours and hours, delivering volley after volley full in their faces.[52]

“Look for the flower to bloom in the silence that follows the storm,” came General Ludlow’s reassuring voice, “not till then.” He was sitting on the parapet of the trenches, under fire, with a copy of Light on the Path.[53]

It shall grow, it will shoot up, it will make branches and leaves and form buds, while the storm continues, while the battle lasts. But not till the whole personality of the man is dissolved and melted—not until it is held by the divine fragment which has created it, as a mere subject for grave experiment and experience—not until the whole nature has yielded and become subject unto its higher Self, can the bloom open.[54]

Meanwhile the battle went forward. The Spaniards were close within their fort and blockhouses; American brigades kept under cover. The valley was empty of life. Toward high noon, in the heat of the day, something the unexpected happened. The fire slackened and ceased. It was time for lunch. For two hours “the fight waited on the camp-fire.”[55]

During this lull General Lawton summoned Major G. Creighton Webb, the inspector-general of his staff, to find, and deliver, important instructions to General Ludlow.[56]

Webb did his work well—during the siege his duties led him, and a guard of five troopers under his command, several times into the “jaws of hell.”

“Don’t go down there, sir” shouted a doughboy. “You’ll be killed,” his voice strobing through the mechanized carnage. “General Ludlow is back there!” he continued, pointing in the opposite direction.

Webb turned around, and galloped his horse through the narrow lane besieged by a tempest of bullets.

“Where is General Ludlow?” Webb asked another soldier.

“General Ludlow—” he said, before a bullet pierced his forehead.

After hours of searching, Webb had yet to find General Ludlow.

“Colonel,” said Webb, as he approached an old officer in the hem of the field, “I’ve been looking for General Ludlow for two hours, and can’t find him. I’ve got five troopers here. I’m not married myself, and of course I don’t care for myself, but they’re all married men, and I’ve got to think of them. I don’t want to risk their lives any more. Now, I’m a tenderfoot, and I ask you frankly what ought I to do?”

“Don’t you report to your superior officer,” the Colonel said, “until you have found General Ludlow!”

That was enough for Webb. Once out of earshot from the Colonel, he gathered his men around him. “You needn’t come,” he said, with frankness and sincerity, “Not one of you.”

Every man came.

As Webb reached the front of the line he heard the familiar click of the Mauser cocking-piece. There, fifty yards in front of them, was a Spanish picket-post with their guns leveled and aiming at him. Webb pressed his body close to his horse, kicked into gallop, and just narrowly avoided the bullets which whistled by. He stopped when the coast was clear.

“Webb,” cried a voice call from the woods, “Webb, my boy, this way!”

“Stoop, sir; stoop,” said a young soldier. As soon as Webb crouched lower, the young soldier took a bullet to his breast.

“Here you are!” called General Ludlow. He was standing straight and proud, with shoulders squared. Webb, never having felt so humble, approximated General Ludlow’s stature by straightening his back.

“General Ludlow,” said Webb “I have a message from General Lawton.”

Webb glanced uneasily at the fallen soldier, and as General Ludlow read Lawton’s message, he took his leave and started off again. He was only about fifty yards out when General Ludlow called him back to the “death hole” of a trench.

Once more Webb left, and once more the General called him back again.

“General,” Webb exasperated, “for God’s sake, don’t call me back any more.”

General Ludlow looked back at Webb and broke into laughter.[57]

A change of plan was called for. At 4:30 p.m. General Ludlow moved one of his regiments about three hundred yards farther to the southwest. This would serve as a blocking force.[58] As the Spaniards endeavored to retreat along the Santiago road, Ludlow’s position enabled him to do very effective work, practically cutting the Spaniards off all the retreat in that direction.[59]

~

“¿Cómo se siente?”

“Como una picadura de mosquito,” said General Del Rey.[60] He looked in wonder at the American soldiers “who fought like lions, and fell like men courting a wholesale massacre.” These Yankee soldiers, stripped to the waist, and offering their naked breast, could have avoided death if they only kept to their firing without storming the trenches. The Spaniards mowed them down by the hundreds, yet they refused to fall back even an inch. As one soldier fell, another would take his place “with grim determination and unflinching devotion to duty in every line of his face.” Their stock ammunition was dwindling fast, they were losing men rapidly, and fighting the battle of despair. The inevitable stared the Spaniards in the face. General Del Rey stood in the square opposite the church when word was brought him that the last round had been served to the men. He at once gave the order to retreat crying to his men ‘Salvese quien pueda!’ He hardly had given the order before he fell—shot through both legs. One of his aides, Lieutenant Joaquin Dominguez, turned to the general as he fell, exclaiming: General, (Que Matanza!) what a slaughter! A bullet took the top clean off his skull, killing him in one shot. In the meantime, four men placed General del Rey on a stretcher and carried him to a place of safety.[61] As they passed from the slaughter-house at Caney, and commenced their retreat down the long white road, the whole line arose, and poured into them a fire through which it seemed impossible to survive. As the General Del Rey lay dying in the road, an American soldier went over to him and gave him a tin cupful of soldier coffee. “Se lo agradezco,” whispered the courtly, white-haired General. Before breathing his last on a hill so far from home, he presented the American with the sword he was wearing when he fell.[62]

~

When Capron’s battery came along, the bugles began to call. At five in the afternoon Ludlow’s brigade moved off in the battery’s wake. A dozen of his men scattered out in an irregular line in the grain-field, moving across it by degrees, stopping now and then to fire. Reporters who saw them from a distance felt their blood galloping through their veins and draw their breath more quickly. The battery held its fire now; the Americans were closing in on the enemy. The end was beginning. The lines which had been inching toward El Caney all day, and suddenly began to concentrate. The soldiers around the battery surged forward to the crest of the sugar-loaf hill, swarming over cannon and caisson toward the battered, shrapnel-shattered blockhouse. They weren’t cheering (though it sounded like it.) No. They were yelling inarticulately some “primitive bellow of exultation.” It was “an echo of the stone age!”[63]

~

The battle was over. The Americans won. That evening General Ludlow surveyed the gruesome aftermath of war. Broken and dead bodies, rubble, barbed wire, blood, and weaponry. The last time he had seen such carnage was with Gen. Sherman, when he was just a boy. It was then when one of his men presented Ludlow with General Del Ray’s sword, and took him to the body. In this muddy palette of tropical war, the Spanish general’s golden-spurs made a striking contrast. A feeling of respect filled the General as he approached the body. General Del Rey died a good death. It was a soldier’s death. His family would be proud of him. His nation would be proud of him. With an almost melancholic reflection, Ludlow knelt by the side of this man who shared the very same grueling battle. The only difference was perspective. There was honor in that. Removing the golden spurs from the boots of General Del Rey was a study in meditation as Ludlow contemplated his own mortality. Who would possess his sword when he left this realm for Devachan? One thing was known. General Del Rey’s sword and spurs belonged with his family in Spain. When Santiago fell a few days later, and Spain finally surrendered, Del Rey’s possessions were handed over to the Spanish General Toral. “Thank you,” General Toral gently uttered, with tears in his eyes.[64]

~

Though Cuba was in American hand, the battle with disease and hunger was an ongoing fight. In the days after the fall of Santiago, Ludlow and Colonel Roosevelt paid a visit to Clara Barton, who was distributing aid on behalf of the Red Cross. They found her being interviewed by a reporter.

“You remember a caller at Constantinople?” the reporter asked her.

“Oh, yes, perfectly. Are we in the same world, or was that a state of existence prior to this? Let me see, we had the Sultan then to talk about, and the Armenians, the Red Cross, the American Ambassador, the Grecian question. It was not this world, it was distinctly another existence.”

The sweet old lady smiled when she remembered the minarets of “old Stamboul,” the Sweet Waters of Asia, and the misty life in the grand capital of the Ottomans.

“For God’s sake Miss Barton,” pleaded Colonel Roosevelt, “don’t send me back to my men without some food and delicacies. A hundred and twenty-one out of four hundred and thirty are sick, and more will be sick.”

Barton placed her tiny, wrinkled hand on the Roosevelt’s shoulder.

“Never fear Mr. Roosevelt, we can help you some. Would six hundred pounds of cornmeal, and say, two hundred pounds of rice with malted milk and condensed milk do for the present?”

“By George!” shouted Roosevelt, like an excited schoolboy. “You are fine, Miss Barton.”

“Whatever you like, Miss Barton, I throw myself entirely on your mercy,” said Ludlow. “My men are sick and dying! A little will help. What you please.”

His bronzed face brightened when he saw Barton estimate how much she could spare.

When Ludlow and Roosevelt left, Barton turned to the reporter, and wrung her hands. “Yes, I helped these generals,” she said. “I have really no right to do so. But poor men, they are so humble–their men are withering like grass, the sick must have malted milk, they clamor for it so. Yes, I’ll give them as long as it lasts. If General Shafter will only give me a receipt for the Red Cross to be satisfied. I can get this back from the government, and so the Cubans will be helped as it was in the first intention of the donors of these supplies. But, I’ll help the American soldiers no matter what comes of it. If the commissary cannot feed a handful of men in time of peace, what would they do with an army equal to that of the Civil War?” She paused before adding, “It will be alright in the end.”[65]

The popularity of Roosevelt soared after the war, and he won the Gubernatorial election of New York State in 1899. He resigned in 1900, however, to be the Vice Presidential running-mate for McKinley. (The details for this were worked out during a dinner hosted by Griscom Sr. at Dolobran, the Griscom family home.)[66]

(Left) General Ludlow’s Residence And Headquarters, Havana.

(Center) Major-General William Ludlow. Military Governor Of Havana.[67]

(Right) Drawing Room Of General Ludlow’s Residence.[68]

After the war, General Ludlow was made Military Governor of Havana, where he occupied a fine palace in a beautiful location just opposite old Cabañas, and commanding a splendid view of the harbor. It was said that during the first two months of American occupation “there were few busier places on the Western Hemisphere than the headquarters of General Ludlow.” He quickly went to work improving the sanitation situation of the city to combat the cholera situation.[69] “With regard to Yellow Fever,” General Ludlow said, “It is always like a dragon, ready to pour out its poisonous breath. We solved the mystery—with the broom and disinfectants.”[70] He also established Havana’s first Theosophical Society.[71] By the end of 1899, the American occupation was coming to an end, and the military authorities were preparing to transition to a civilian government in Cuba. ”Among the final preparations for the full assumption of authority by the Cubans will be the election of a constitutional assembly,” General Ludlow told the press.[72]

In February 1900, Ludlow and Evie went to New York. Evie was to travel with Genevieve and Clem to Constantinople, where Lloyd Griscom was now installed.[73] Ludlow briefly returned to Havana, but was back living in the States by early April. (The Theosophical Convention in April 1900, however, states that he was still the representative of the Havana Theosophical Society.)[74] In the summer of 1900 he was sent to Berlin, Germany, to inspect their War College “with a view to the creation of a similar organization in the United States.”[75]

McKinley Inauguration, March 4, 1901, Washington, D.C.[76]

On March 4, 1901, Ludlow was in Washington, D.C., leading the military escort for President McKinley (who was delivering his second inaugural address.)[77] Having recently been promoted to Military Governor of the Department of the Visayas (Philippines,) General Ludlow was particularly invested in the substance of President McKinley’s speech.[78] The President said:

The Congress having added the sanction of its authority to the powers already possessed and exercised by the Executive under the Constitution, thereby leaving with the Executive the responsibility for the government of the Philippines, I shall continue the efforts already begun until order shall be restored throughout the islands, and as fast as conditions permit will establish local governments, in the formation of which the full cooperation of the people has been already invited, and when established will encourage the people to administer them […] The Government’s representatives, civil and military, are doing faithful and noble work in their mission of emancipation and merit the approval and support of their countrymen […] Our countrymen should not be deceived. We are not waging war against the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands. A portion of them are making war against the United States. By far the greater part of the inhabitants recognize American sovereignty and welcome it as a guarantee of order and of security for life, property, liberty, freedom of conscience, and the pursuit of happiness.[79]

He was very sanguine over the situation with the rebels there. “The military difficulty is practically over,” Ludlow would say. “It will now be necessary for the government to suppress brigandage, stop smuggling, and maintain peace and order so the development of the country can proceed.”[80] On March 26, 1901, General Ludlow arrived in Honolulu, Hawaii, en route to the Philippines, to take up his new post as Military Governor.[81] He told the local reporters. “The problem in the Philippines which confronts us is now of a civil character. The Filipino is like the Cuban and, in fact, all of the colonists of Spain. He thinks that political liberty means personal liberty. They never were permitted any voice in the government of the islands, and they do not understand the theory by which our government is conducted. The principle by which the majority whenever any leading issue is determined, is beyond his comprehension. He thinks that if things go against him, he can quit, throw up his hands and have nothing more to do with affairs. He wants to go out and run amuck and kill people in order to be revenged.”[82]

General Ludlow’s health had been excellent until he entered the sweltering climate, and “miasmatic atmosphere” of Manila. He was determined to fight through whatever malady he contracted, convinced that his body would acclimate to the tropics. As time passed, however, even the General was forced to admit that his health was failing. The army board of surgeons determined that General Ludlow suffered from an attack of grippe and localized congestion, which developed into a dangerous case of tuberculosis. His appointment at Military Governor was revoked, and he was ordered to the United States, believing that the more temperate climate of his home would restore his strength and vigor.[83] Evie Ludlow met her husband and Captain Slaker the minute the transport Buford from Manilla arrived in Honolulu on June 14. Evie then gently guided the General to the private residence where they were staying before continuing onward to New Jersey.[84]

Earlier that year Genevieve and Clem moved the family from Flushing to Convent, New Jersey, a community in the eastern section of Morristown.[85] By 1900, Morristown had become home to one of the largest communities of millionaires in the nation.[86] Following the trend of their peers, Clem and Genevieve moved into an estate just opposite the colonial-style Morris County Golf Club.[87] When the weather permitted, the General would take strolls on the lawn or relax on the veranda. The pure mountain air of Morristown, free from the contamination of the city, was noted for its restorative health properties. Physicians in New York, and other cities, often sent their patients here to regain their vitality. Even the scenery, the guidebooks said, recalled “the many beautiful descriptions of nature found in the mountains of Switzerland.” When General Ludlow first arrived, everyone feared the worst. It seemed, however, that he would make a full recovery.[88]

Morris County Golf Club.

Though Morristown held the honor of being the birthplace of the telegraph, it was George Washington, who made camp here, that put the village on the map. The building Washington lived in had recently been purchased by the Washington Society of New Jersey. They opened it as a museum to the public.[89] Perhaps General Ludlow reflected on his great-grandfather, Obadiah Ludlow, who was Washington’s “right-hand man,” throughout the entire Revolution.[90] “By both lines,” General Ludlow wryly mused, “I descended from notable colonial stock.”[91]

(Left) Mary Enid Evelyn (née Guest), Lady Layard. (Source: National Portrait Gallery, London.)[92]

(Right) Bowling Green, Manhattan.[93]

On August 24, 1901, Clem met his sister, Frances Griscom, and brother-in-law, Samuel Bettle (Helen Griscom’s husband) at the wharf of the American Line. They were escorting Evelyn Layard to Dolobran, where she was staying as a guest of the family.[94] Evelyn, the widow of Austen Layard (the Assyriologist who excavated Nimrud and Nineveh,) was an old friend of the family. After clearing the authorities, Clem took her back to his office at Bowling Green where they were met by Griscom Sr. The party then took a Pullman car especially prepared for Griscom Sr. (a director of Pennsylvania Railroad) to Philadelphia. By dinner time that evening Griscom Sr. had arrived from Manhattan “which added much hilarity and jollity to the evening.” After dinner everyone retired to a large parlor called the Art Room, where Helen worked a “pianola” for Evelyn’s amusement. The Art Room contained many fine pictures by Lawrence, Sir Joshua, Van der Helot, and Romney. Here, too, were the fine portraits of the Griscom women by the renowned painter, Cecilia Beaux (the only woman on the international jury whose paintings were sent to the Paris Exposition.)[95] There was also the taxidermized Buffalo head, a trophy from General Ludlow’s Black Hill’s Expedition with Custer.[96]

Mother and Daughter (Frances C. Griscom and Pansy C. Griscom) by Cecilia Beaux.

On August 30 Griscom Sr. took an early train to Manhattan (Clem had already returned to Morristown to be with Genevieve and General Ludlow.) Frances and Evelyn followed Griscom Sr. to New York on the 9 a.m. train. There they spent the day shopping. (The Spanish ladies in Cuba, now impoverished by Spanish American War, were selling their jewels for cheap in New York.) Frances and Evelyn met Griscom Sr. at Delmonico’s for lunch. After their meal they took a train to Whitestone where they boarded Griscom Sr.’s yacht, “Alert,” and “sailed along merrily in perfectly smooth waters.”[97]

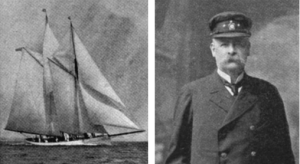

(Left) “Alert.” (Right) Griscom Sr.[98]

They arrived in Newport, Rhode Island, on September 1, 1901, to attend the first official trial race held by the New York Yacht Club.[99] The mood was dampened when they learned that General Ludlow had died on August 30, 1901. It was raining all morning, so everyone gathered under the awning to talk. When the weather cleared, Frances took Evelyn on board “Josephine,” George Wideners big steam yacht, where a select party was assembled.[100] The following day the Griscom party were invited aboard J.P. Morgan’s steam yacht the “Corsair,” to witness a trial race between the “Constitution” and the “Columbia” out at sea. While Frances and Evelyn sat on deck talking, they were paid a visit by Katherine Berwind, wife of John E. Berwind.[101] As they sailed past Griscom Sr.’s summer home at Watch Hill, Frances heard Pansy calling from the water. They laughed when they found her and Rod—both in bathing costumes—paddling in a canoe. They had seen the “Alert” while they were out bathing and had seized a small canoe to come out to speak with them. Pansy and Evelyn went off in their best gowns to the Horseshoe Casino, where they settled themselves in with Katherine Berwind. Later that day Griscom Sr. and J.P. Morgan sailed for New York in the Corsair to attend General Ludlow’s funeral.[102]

Horseshoe Casino, Newport, Rhode Island.

General Ludlow’s body arrived at Hoboken Station at 11 a.m. on the morning of September 3rd. It was met by a military escort composed of eight hundred officers and men of the Engineers and Coast Artillery. The coffin, the mourners, and the military escort, were placed on a special ferryboat and crossed over to the other side of the river. They arrived at Barclay Street. A line of march was formed. The funeral procession traveled east on Barclay, then South on Broadway, and from there to Trinity Church.

“Bearing the Body Of Brigadier-General Ludlow Into Trinity Church.”[103]

The pallbearers in their carriages followed the caisson. Evie, Admiral Ludlow, Genevieve, Clem, Acton, and Ludlow—and a number of military friends—made up the rear. The front of the procession approached Trinity Church. The line broke. The soldiers made formations on both sides of the street. Through this aisle, the caisson passed. The band was now playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” In Long Island City the funeral party embarked a special train for Fresh Pond Cemetery, where General Ludlow’s body was cremated.[104] Although William Ludlow “did not die in battle as he hoped to do, he died with flags flying and his soul erect.”[105] In The Theosophical Forum a memorial was dedicated to the fallen Theosophical comrade: “It is a part of the strange, deceptive quality of things, that nothing should teach us so much of life, nothing should so much open our eyes to the grandeur and limitless possibility of life, as death, which is called the cessation of life.”[106] In the years following his death, Genevieve would write down a collection of her favorite admonitions given to her father:

Always to be courteous and gracious, to everyone, but with reserve. Never forget your dignity.

To speak always in a low and well-modulated voice. (Loud talking he abhorred.) Never interrupt.

Never be an eager talker, and above all be a good listener. (This last, he said, was a great charm in man or woman,—an irresistible charm in a woman.)

To be careful in English and the choice and use of words, and in accent and pronunciation. Never to use slang, and to be careful even with colloquialisms.

Never to listen to flattery, nor to pay too much attention to what anyone said—save a very few.

Never to ask personal questions, and to use discretion in commenting on information given you.

Never explain. A woman is lost if she explains herself!

Never to give yourself right and left to people. To go extremely slow. To trust only after much testing. Violent intimacies are vulgar.

When a friend is made, to be as true as steel; and to stand like a rock behind those who serve you.

Your friendship and your service should be something worth winning— and hard to win.

To set a high price on yourself, and then to make yourself worth the price.

To be sufficient to yourself, if need be, and to have no companions rather than poor ones.

Always to do what is right. Never mind the consequences: they will take care of themselves.

A man is known by the company he keeps; he is also to be known by the enemies he makes. A man who has no enemies cannot amount to much. He stands for nothing. The evil and the low should hate and fear you, as you them. To be a good hater, otherwise you cannot be a true lover.

To mind your own business, and to keep your opinions to yourself. It is not often that anybody wants them!

To eliminate curiosity, which is extremely vulgar.

If you ever hear anything about someone’s else affairs, to forget it instantly.

Never to tolerate anything unworthy in your presence: to make everyone feel that such things are impossible there.

Always to be cheerful and encouraging; to give people hope and to stimulate them. The less cheerful you feel, the more cheerful you should be. Never to spare yourself, your time, your strength, or your money, in service of others. Never to talk about your troubles, or your aches and ails. To try to ignore them to yourself. When you are suffering too much to be able to hide it, to shut yourself up in your own room until you have mastered it.

No matter how afraid you are, never to let on.

No matter how hurt you are, never to let on.

If you cannot begin by being courageous, you will end there, by keeping these two rules.

To be afraid of nothing except dishonour: there is nothing else to be afraid of.

Never to neglect a duty; never to shirk a responsibility; to do either is dishonorable.

To defend your principles and your honor to the last drop of your blood. They are the only things in the world that count.

To loathe a lie above all things—and liars. To be incapable of such yourself.

Never to flinch under a threat, not even from life itself.

To obey instantly, without question, those in authority. You owe it to yourself.

Never to forget that you are a soldier’s daughter. “ Never to forget that you are a Ludlow.

To be true to the colors.

Noblesse oblige.[107]

SOURCES:

[1] Frost, G. H. “Statement.” Engineering News. Vol. VIII (April 9, 1881): 147-149.

[2] Meade, Marion. Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1980): 132.

[3] Woodbridge, George. “‘Volunteer’ Or ‘Pressed’ Man.’” The Theosophical Quarterly Vol. XXIII, No. 3. (January 1927): 248-253; “Obituary” The British Chess Magazine. Vol. X, No. 114. (June 1890): 229-230; Ancestry.com. Maine, U.S., Marriage Index, 1670-1921 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016; Woodbridge, George. “‘Volunteer’ Or ‘Pressed’ Man.’” The Theosophical Quarterly Vol. XXIII, No. 3. (January 1927): 248-253.

[4] “An Epitome of Theosophy.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 3, 1892

[5] Carosso, Vincent P. The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854-1913. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (1987): 246-249; Burt, Nathaniel. The Perennial Philadelphians: The Anatomy of an American Aristocracy. University of Pennsylvania Press. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1999): 448.

[6] “Fifty Dollars For A Cigar.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. (St. Louis, Missouri) June 5, 1884.

[7] Ludlow, William. “Pollution Of The Schuylkill River Within The Limits Of The City Of Philadelphia.” The Sanitary Engineer. Vol. X, No. 18 (October 2, 1884): 411-412.

[8] Ludlow, William “The Water Supply Question And The Cholera.” Bradstreet’s. Vol. XI, No. 351 (March 21, 1885):183.

[9] “The Universal Tribute.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) August 8, 1885.

[10] “Harbor Improvements.” The Times. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) September 1, 1881; “A Memorial.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) July 3, 1882; “Improving The Harbor.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) August 12, 1882; Thirty-Third Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Seeman & Peters, Printers and Binders. Saginaw, Michigan. (1902); Flayhart, William H. The American Line: 1871-1902. Norton. New York, New York. (2000): 79-91.

[11] Morgan, Kenneth W. Memories. Unpublished. 257-277.

[12] “A Notable Reception.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) January 18, 1886.

[13] “Hail! Wedded Love: A Long List of Marriages and Engagements in Philadelphia.” The New York Herald. (New York, New York) November 18, 1888.

[14] The National Cyclopedia Of American Biography: Vol. IX. James T. White. New York, New York. (1899): 23.

[15] “Bride Is Niece Of Hancock.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) September 19, 1889; “Wired From The City.” The Boston Herald. (Boston, Massachusetts) September 19, 1889.

[16] “T.S. Activities.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XX, No. 1. (July 1922): 70-96.

[17] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 5447. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Genevieve Ludlow Griscom; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 5635. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) William Ludlow.

[18] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 7651. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Louise Nicoll Ludlow. [Hartshorne, Indian Territory. (11/12/1891.)]

[19] F.T.S. (William Ludlow) “What is Theosophy?” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) December 20, 1891; F.T.S. (William Ludlow) “An Epitome of Theosophy?” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 3, 1892; F.T.S. (William Ludlow) “Theosophy?” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 17, 1892; F.T.S. (William Ludlow) “Theosophy?” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 24, 1892; F.T.S. (William Ludlow) What Is Theosophy?: Letters Written To The Detroit Free Press. Printed By The Staten Island Branch. Thomas J. Brashears’ Sons. Washington, D.C. (No Year Listed); “Fifty Years.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIII, No. 3 (January 1926): 209-211.

[20] “Colonel Ludlow Relieved From Duty.” The Sun. (New York, New York) June 22, 1892.

[21] “Will Be Restored.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) March 12, 1893.

[22] “Purely Personal.” The Lincoln Nebraska State Journal. (Lincoln, Nebraska) December 11, 1893.

[23] Davis, William E. Dean of the Birdwatchers: A Biography of Ludlow Griscom. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. (1994):.64.

[24] “First From The New Pier.” The Evening World. (New York, New York) January 3, 1894.

[25] “Roosevelt’s Double Denial.” The Evening World. (New York, New York) November 1, 1893.

[26] “Mrs. Roosevelt Dead.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) November 13, 1893.

[27] Griscom, Lloyd C. Diplomatically Speaking. The Literary Guild Of America. New York, New York. (1940): 26, 66.

[28] “London Personals.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) February 26, 1894.

[29] “Yale Boys Are Feasted.” The St. Paul Globe. (Saint Paul, Minnesota): July 18, 1894.

[30] “Death Of Czar Alexander III.” The Oxfordshire Weekly News. (Oxfordshire, England) November 7, 1894; “Plans For Alexander’s Funeral.” The Chicago Tribune. (Chicago, Illinois) November 7, 1894.

[31] Ludlow, William. “The Military Systems Of Europe And America.” The North American Review. Vol. CLX, No. 458. (January 1895): 72–84.

[32] United States. 54th Congress. First Session. House Of Representatives. Document No. 279. Nicaragua Canal. Message From The President Of The United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. (1896): Appendix A. Minutes Of The Nicaragua Canal Board.

[33] Ludlow, William. “The Trans-Isthmian Canal Problem.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Vol. XCVI, No. 576. (May 1898): 837-846.

[34] Supplement to The Theosophical Forum Vol. II. No. 10. (February, 1897)

[35] “On The Screen of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIV, No. 2 (October 1926): 163-175.

[36] “On The Screen of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIV, No. 2 (October 1926): 163-175.

[37] “Jose Maceo’s Death.” The Hawaiian Gazette. (Honolulu, Hawaii) August 7, 1896.

[38] “Great Victory For Cuba Libre.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) March 7, 1897.

[39] “Victoria’s Jubilee.” The Abbeville Press And Banner. (Abbeville, South Carolina,) July 7, 1897.

[40] “New York Is In No Danger.” Chicago Tribune. (Chicago, Illinois) March 13, 1898.

[41] Davis, Richard Harding. The Cuban And Porto Rican Campaigns. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York, New York. (1898): 104.

[42] Lodge, Henry Cabot “The Spanish American War: Santiago” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine Vol. XCVII, No. DLXXXVIII (May, 1899): 833-862.

[43] “Our Officers Visit Garcia.” The Herald. (Los Angeles, California.) June 22, 1898; Miley, John D. In Cuba With Shafter. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York, New York. (1899): 75-80.

[44] “The Battle Of El Caney.” The New York Times. (New York, New York.) August 14, 1898.

[45] “The Battle Of El Caney.” The New York Times. (New York, New York.) August 14, 1898.

[46] Lee, Arthur H. “The Regulars At El Caney.” Scribner’s Magazine. Vol. XXIV, No. 4. (October, 1898): 403-413.

[47] Holloway, A. Hero Tales Of The American Soldier And Sailor. Elliott Publishing Company. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1899): 272-273.

[48] Norris, Frank. “With Lawton At El Caney.” The Century. Vol. LVIII, No.2 (June, 1899): 304-309.

[49] Konstam, Angus. San Juan Hill 1898: America’s Emergence as a World Power. Bloomsbury Publishing. New York, New York. (2013): 52.

[50] Vivian, Thomas Jondrie. The Fall Of Santiago. R.F. Fenno & Company. New York, New York (1898): 143-148.

[51] Konstam, Angus. San Juan Hill 1898: America’s Emergence as a World Power. Bloomsbury Publishing. New York, New York. (2013): 52.

[52] Chamberlin, Joseph Edgar. “How The Spaniards Fought At Caney.” Scribner’s Magazine. Vol. XXIV, No. 3. (September, 1898): 278-282.

[53] T. “On The Screen Of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXVI, No. 2 (October, 1928): 278-282.

[54] Collins, Mabel. Light On The Path. Cupples, Upham, And Company. (1886): 11-12.

[55] Norris, Frank. “With Lawton At El Caney.” The Century. Vol. LVIII, No.2 (June, 1899): 304-309.

[56] General Lawton’s report July 3, 1898 in 55th Congress, 3d Session, House of Representatives, Document no. 2. Annual Reports of the War Department for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1898. Report of the Major-General Commanding the Army. Washington: Government Printing Office (1898.) 169.

[57] Harper’s Pictorial History Of The War With Spain. Harper & Brothers Publishers. New York, New York. (1898): 384.

[58] Tucille, Jerome. The Roughest Riders: The Untold Story of the Black Soldiers in the Spanish-American War. Chicago Review Press. Chicago, Illinois. (2015): 239-279.

[59] Holloway, A. Hero Tales Of The American Soldier And Sailor. Elliott Publishing Company. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1899): 191-192.

[60] Castellanos Garcia, Gerardo. Tierras y Glorias de Oriente. Hermes Havana. (1927): 334-337.

[61] “The Fight For El Caney” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York.) June 22, 1898.

[62] Captain Stewart. “In The Cuban Campaign.” The Norton Courier. (Norton, Kansas) April 2, 1914.

[63] Norris, Frank. “With Lawton At El Caney.” The Century. Vol. LVIII, No.2 (June, 1899): 304-309.

[64] “Shafter’s Defense; First Reply to Critics.” The New York Journal And Advertiser. (New York, New York) November 26, 1898.

[65] MacQueen, Peter. “Clara Barton To The American People.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XLVII, No. 1. (November, 1898): 76-82; MacQueen, Peter. “Aftermath At Santiago.” The National Magazine. Vol. VIII, No. 6. (September, 1898): 499-506.

[66] “Roosevelt the Man.” The Bourbon News. (Paris, Kentucky) June 19, 1900.

[67] “American Officers In Charge In The Capital And Their Officials.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. XLIII, No. 2210. (April 29, 1899): 431

[68] “American Officers In Charge In The Capital And Their Officials.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. XLIII, No. 2210. (April 29, 1899): 431

[69] Matthews, Franklin. “The Reconstruction of Cuba.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. XLIII, No. 2204. (March 18, 1899): 271-272.

[70] “Ludlow Talks On Cuba.” The New York Times . (New York, New York) November 17, 1899.

[71] “Theosophical News And Notes: The Convention” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. V. No. 1. (May 1899): 11-19.

[72] “General Ludlow On Cuba.” The Washington Times. (Washington, D.C.) November 9, 1899.

[73] “General Ludlow On Cuba.” The St. Louis Globe-Democrat. (St. Louis, Missouri) February 15, 1900; “Gen. Ludlow Returns From Havana.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) April 18 , 1900; Griscom, Lloyd C. Diplomatically Speaking. The Literary Guild Of America. New York, New York. (1940): 161.

[74] “American Theosophists Meet.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) April 30, 1900.

[75] “Gen. Ludlow In Berlin.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) July 29, 1900.

[76] Inauguration of Pres. McKinley. Washington D.C, 1901. [March 4] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/00652337/.

[77] “Inauguration is Over.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) March 5, 1901.

[78] “General Ludlow Very Ill.” The Sandusky Star-Journal. (Sandusky, Ohio) April 27, 1901.

[79] McKinley, William. March 4, 1901: Second Inaugural Address. National Archives.

[80] “Many Soldiers In Town” The Hawaiian Star. (Honolulu, Hawaii) March 27, 1901.

[81] “General Ludlow Very Ill.” The Sandusky Star-Journal. (Sandusky, Ohio) April 27, 1901.

[82] “Many Soldiers In Town” The Hawaiian Star. (Honolulu, Hawaii) March 27, 1901.

[83] “General Ludlow Very Ill.” The Sandusky Star-Journal. (Sandusky, Ohio) April 27, 1901.

[84] “Praise For Philippines.” The Commercial Advertiser. (Honolulu, Hawaii Territory) June 15, 1901.

[85] “Morristown, New Jersey, City Directory, 1903.” p.99. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

[86] Nadzeika, Bonnie-Lynn. Morristown. Arcadia Publishing. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. (2012): 7.

[87] “With The Golfers.” The Amateur Athlete. Vol. III. No. 11. (New York, June 3, 1897): 7.

[88] “Death Of A Hero.” The Plymouth Republican. (Plymouth, Massachusetts) September 5, 1901.

[89] Chapin, B.E. Outings on the Lackawanna. Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. New York, New York. (1899): 34-35

[90] “Mr. Speaker Ludlow.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) January 22, 1853.

[91] McAndrews, Eugene V. William Ludlow: Engineer, Governor, Soldier. [Doctoral Dissertation.] Kansas State University. Manhattan, Kansas.

(1973): 1.

[92] Mary Enid Evelyn (née Guest), Lady Layard. National Portrait Gallery, London. Creative Commons.

[93] The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Beginning of Broadway in 1899” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed June 26, 2023.

[94] “Came on St. Paul.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) August 25, 1901.

[95] “The Lounger.” The Critic. Vol. XXXV, No. 870. (December 1899): 1072; Layard, Enid Evelyn, “Journals Of Mary Enid Evelyn Layard,” 1869-1912. Abbott, Edith and Grace. Papers, [Add MS 46153-46170: 1869-1912], Western Manuscripts, The British Library. (24 August 1901 entry.)

[96] Rawdon, Clara Hale. “What We Are Doing And Chapter Work.” The American Monthly Magazine. Vol. IX. (July-December 1896): 31-35.

[97] Layard, Enid Evelyn, “Journals Of Mary Enid Evelyn Layard,” 1869-1912. Abbott, Edith, and Grace. Papers, [Add MS 46153-46170: 1869-1912], Western Manuscripts, The British Library. (30 August 1901 entry.)

[98] Brown, Harry. The History of American Yachts and Yachtsmen. Spirit Of The Times Publishing Company. New York, New York. (1901): 111.

[99] “Old Defenders Race.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) September 1, 1901.

[100] Layard, Enid Evelyn, “Journals Of Mary Enid Evelyn Layard,” 1869-1912. Abbott, Edith, and Grace. Papers, [Add MS 46153-46170: 1869-1912], Western Manuscripts, The British Library. (1 September 1901 entry.)

[101] “J.E. Berwind Dies Of Heart Attack.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) May 24, 1928.

[102] Layard, Enid Evelyn, “Journals Of Mary Enid Evelyn Layard,” 1869-1912. Abbott, Edith, and Grace. Papers, [Add MS 46153-46170: 1869-1912], Western Manuscripts, The British Library. (September 2, 1901, entry.)

[103] “Funeral of Gen. Ludlow.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) September 4, 1901.

[104] “Gen. Ludlow’s Funeral” New York Times (New York, New York) September 1, 1901; “General Ludlow Dies Suddenly.” Chicago Daily Tribune, (Chicago, Illinois) August 31, 1901; “Brig. Gen. Ludlow Dead.” The New York Times (New York, New York) August 31, 1901; “Funeral of Gen. Ludlow.” The New York Tribune, (New York, New York) September 4, 1901.

[105] “On The Screen of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIV, No. 2. (October 1926): 163-175.

[106] “In Memory Of William Ludlow.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VII, No. 5. (September 1901): 81-83.

[107] “On The Screen of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIV, No. 2. (October 1926): 163-175.