The world is full of mysterious objects, and the British Museum has stolen most of them!

You don’t build the biggest collection of historical pieces on Earth without making some enemies, and the British Museum has made many. Having plundered the globe for such a comprehensive representation of cultures, these famed exhibitions have provoked much understandable controversy. Simply put, countries want their stuff back! Noted requests come with additional potency when the items in question are of spiritual value and can be assessed as sacred specimens of religious mythology. In that regard, there is surely no location on UK soil more cursed than what you find among these fruits of divine disruption.

In Defense of the British Museum

However, one cannot argue against the care that the British Museum puts into preserving these items. They pedantically maintain their pristine condition while organising them in a logical, easy-to-locate manner. Conversely, many of their countries of origin have proven the opposite, displaying priceless artefacts in eroding condition, either weathered by the elements or haphazardly shoved onto a disarrayed shelf in a maze of a building. That is why some argue that these blessed relics, with all their godly powers, have actually chosen to be here.

Be that as it may, one could never justify the shameful thievery of British past. However, there is no mistaking the unparalleled grandeur of this essential London establishment. Its permanent collection of eight million pieces is a celebration of human history, allowing anyone to explore the holiest places on the planet without paying a single penny. They do request donations, but I myself refused out of moral principle. I will not support your crimes even if I enjoy looking at them!

Here are the top 10 holiest items currently exhibited in the museum. I hope this article helps you to map out your next treasure hunt.

1. Hoa Hakananai’a

Hoa Hakananai’a is a moai statue sacred to the Rapa Nui of Easter Island. These people believe that the sculptures harness “the spirit of the ancestors,” which is feasible considering how unimaginable it is that they even exist. Erected between 1250 and 1500 AD, historians are still unsure how such colossal stones were moved across the island. Was it pure manpower? Were there pulley systems involved? Were they the walked by rocking from side to side? Only the gods know. Or perhaps… the aliens? But that’s a conversation for another time.

A British ship grabbed this fella in 1868. Due to some carvings in its back, experts have connected it with Easter Island’s birdman cult. Meanwhile, the Rapa Nui stand firm that this dude is stolen goods, and there have been loud demands for its return. The museum has offered to loan the statue to its rightful owners, but they are not yet ready to give up such a central piece to their collection. So, if you enjoy staring at this remarkable statue, why not send some tourism to Easter Island and visit the rest of them in person? It’s the least you can do to clean your karma.

2. Rosetta Stone

Without a doubt, the most renowned artefact in the British Museum is the Rosetta Stone. Dating back to 196 BC in Rosetta (duh), Egypt, we cannot overstate its historical importance. Chipped into its surface is a decree praising King Ptolemy’s wise rule, written in three different languages. At the top, we have Egyptian hieroglyphs (the language of the gods). In the middle is the Egyptian Demotic script. And at the bottom, Ancient Greek. Using these references, linguists could unlock a new realm of translation possibilities; hence, the name “Rosetta Stone” has become synonymous with language learning.

The French discovered and stole the rock in 1799. However, after defeating the French in battle, The British plucked the stone for themselves in 1801. Calls to return the steel to Egypt have been ongoing since 2003 but have, thus far, fallen on deaf ears. As British Egyptologist John Ray noted, “The day may come when the stone has spent longer in the British Museum than it ever did in Rosetta.”

3. Younger Memnon

Remaining in Egypt, here’s a colossal piece, both in size (standing at an impressive 8 feet 10 inches) and historical significance. Meet the Younger Memnon, featuring the likeness of Pharaoh Ramesses II from the Nineteenth Dynasty, painstakingly carved from a single granite block in 1270 BC. Interestingly, the lower half of this monument still resides in Egypt, albeit in a less-than-ideal condition (see this digital restoration for comparison).

Ramesses II (or Ramesses the Great) ruled the New Kingdom from 1279 to 1213 BC. During this reign, he led at least 15 military campaigns, each one victorious. Historians recognise him as one of the most powerful and well-loved Pharaohs of all time. It is also worth remembering that Pharaohs held a sacred role as intermediaries between ordinary people and the gods. This context adds a profound spiritual resonance to objects like these.

The British Museum has more Egyptian antiquities than anywhere else in the world besides the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Their 100,000+ pieces may be a spectacular feature of the establishment, but it exposes how Egypt’s land was truly ransacked, most notably during the colonial era. Conversations to rectify these wrongs are said to be ongoing, but as of yet, the museum has been unmoveable in its contents.

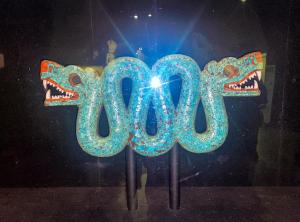

4. Double-Headed Serpent

When comparing the ancient civilisations represented within these walls, the Aztecs are relatively new on the scene. Take this piece, for example. Created between 1400 and 1521 AD, the Double-Headed Serpent feels like it was put together just the other day.

Nevertheless, this treasure stands as a testament to the Mesoamerican‘s impressive craftsmanship. Using pine resin, they fixed 2,000 miniature pieces of turquoise stones to a wooden body. The varying sizes ingeniously create a curvilinear illusion. Believe it or not, this ornament is entirely flat.

As with many cultures, the Aztecs revered serpents as symbols of rebirth, reflecting the creature’s ability to shed old skin and emerge renewed.

5. Parthenon Marbles

The Greek Parthenon’s Metopes, crafted under the guidance of Phidias circa 446 BC, narrate the tales of Athens City’s triumphs. Unfortunately, many of these extraordinary pieces faced destruction during the sixth or seventh century AD. Like so many global stories, Christianity came along and demanded that Ancient Greece move away from its traditional polytheistic canons, even turning the Parthenon into a church.

The majority of these Metopes were damaged and now reside in the British Museum. According to official sources, most of these pieces were obtained legally through an acquisition by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin (hence their name, The Elgin Marbles). Regardless, there are slow discussions to facilitate their return to Greece. It’s a curious conflict, considering how the nations are otherwise on friendly terms. I don’t treat my friends like this.

6. Holy Thorn Reliquary

Our story starts in 1239 when King Louis IX of France acquired what was believed to be the “authentic” Crown of Thorns worn by Jesus. Such a phenomenal piece of religious lore meant numerous greedy digits hovered around, and over time, segments of this sacred relic were snapped off and sold separately to the highest bidder. Here is one of those pieces: a thorn claimed to have dug into Christ’s skin during the most world-changing event in history.

The purported remnants of this crowd are spread across the world (most notably in the Notre Dame de Paris). However, we must pay our respects to this exquisite display, where the wood is housed in a gold case and adorned with an array of jewels and pearls. Even if you do not believe in the authenticity of the relic, the presentation alone is a splendour of craft magnificence. Plus, it wasn’t stolen!

7. Shiva Nataraja

When studying the seemingly infinite canon of Hindu gods, no one can avoid the trinity that sits on top. We have Brahma, the creator. We have Vishnu, the preserver. And then we have Shiva, the god of destruction who will ultimately destroy the universe one day. He will achieve such a feat by becoming Nataraja and performing a little dance called the Tandava. And just like that, everything you’ve ever known and loved will be gone.

This statue showcases Lord Shiva in the middle of the dance. Some talented person in India cast the iron around a millennium ago and it is considered one of the most expertly crafted versions on the planet. Funny enough, India has not made any claims to repatriate this artefact, claiming good relations between their respective museums. Classic Hindus!

8. Kayung Totem Pole

Built by the Haida people on Graham Island (British Columbia, Canada) around 1850, the Kayung Totem Pole stood proudly as a towering masterpiece of artistry and culture. Less than 50 years later, its home village was nearly abandoned due to an outbreak of smallpox. That’s when ethnographic researcher Charles F. Newcombe claimed the piece, eventually selling it to The British Museum. Naturally, the museum was happy to have it, but considering the insane height of the thing (39 feet!), they could only fit it in the stairwell for most of its stay! Thankfully, it now resides in the Great Court.

There are two surreal folktales about the pole told by the Haida people. One concerns the raven trickster Yetl losing his beak, while the other is about a shaman swallowed by a whale. If you are interested, you can find those Haida tales here.

9. The Bronze Head from Ife

It is believed that this head represents Obalufon Alayemore. He was an Ooni (king) of Ife, Nigeria, who probably ruled in the 1300s or early 1400s. Through the eyes of the Yoruba spiritual practice, he is now acknowledged as a deity.

In 1938, eighteen copper artefacts were unearthed, including this one. The British experts of the time initially refused to believe that these were crafted in Nigeria because it undermined their racist beliefs that the savage Africans were incapable of such craft. Ethnologist Leo Frobenius even proposed that these sculptures were of Greek origin, fueling the legends of the lost civilisation of Atlantis. Such prejudices are long disproven, and these African pieces played a significant role in challenging the ugly perspectives of the West.

10. Lely Venus/Crouching Venus

The Roman Venus (or Aphrodite, if you prefer your Greek variations) is the goddess of love, desire, beauty, and fertility. There are many myths associated with her backstory, but this statue snapshots a specific moment in time. As the legend goes, she was enjoying a bath, minding her own business, when the mischievous god Mars (or Ares) tried to sneak a peek at her. Upon realising there was a pervert in the proximity, Venus quickly protected her modesty. Here she is, mid-cover-up.

An impressive amount of statues exist of this moment, but the example here has been called “the finest statue of all”. The Italian Gonzaga collection first recorded this Venus in 1627, but we assume it is much older than that. Currently, it is part of the Royal Collection and is only on loan to the museum.