Harper Feist’s Io Typhon is a devotional text dedicated to the misunderstood Typhon-Set whom she describes as “an amorphous, syncretic deity from late antiquity who appears predominantly in the Greco-Egyptian Magical Papyri – a series of ancient spells unearthed from a tomb in Thebes. He is a fascinating amalgam of the deicidal Greek proto-monster Typhon Typhon and the antagonistic Egyptian god Set.”

Ms Feist’s text contains eight hymns to Typhon-Set, accompanied by magnificent sigils and artwork produced by esoteric artist, Rowan E Cassidy.

I would advise readers not familiar with Typhon-Set to start at the end of the text for a comprehensive explanation of the god they’ll be working with.

Ms Feist quotes Hesiod’s writings on Typhon and points out that he seems to have come from the Near East. He had rebelled against the reign of Zeus and had freed the Titans from the Olympians. Ultimately the rebellion failed.

Set was “the Egyptian god of war, foreigners, chaos, and storms” and was known for killing and dismembering his brother, Osiris, in an effort to win his spouse, Isis. This led to numerous battles with their son, Horus. Set was “a god of division and destruction, an avatar or confusion. And yet the fury of Set had a function, for he was instrumental in the war against Apep, the Chaos-Serpent. As the solar boat descended into the depths of the Duat each night, Set fought side-by-side with Horus and Ra to drive back Apep so that the sun might rise again at dawn. A king in his own right, Set was lord of the Red Land (ie the desert) as Horus was lord of the Black Land (is the fertile Nile Valley).”

Ms Feist points out that Hecataeus of Miletus, Pindar, Herodotus and others equated Set with Typhon, reinforcing their combined role as gods of chaos and storms. By late antiquity this combination led to Typhon-Set: “the sorcerer’s god of rebellion, destruction – and change.”

The uncertainty of change has always been feared, yet it is necessary to avoid stagnation. Ms Feist points out that we our world is in constant flux including technology, politics, gender and sexual mores. She adds that in the face of constant change it makes sense to make an allegiance with a god presiding over change. Typhon-Set destroys and old and unnecessary to make room for the inevitable and new. Ms Feist points out that “he is the god of our age, The time for his worship has come.”

The hymns form a sequence presumably mirroring Ms Feist’s journey in devoting herself to Typhon-Set. Let’s look at the hymns sequentially.

The first hymn is a meditation on Hesiod’s description of Typhon as having one hundred snake heads on his shoulders.

The second hymn is a meditation on the nature of Typhon-Set, and as such builds in the first hymn and adds in Setian imagery.

The third hymn will be of great interest to Thelemites, where Ms Feist intersperses verses from Aleister Crowley’s Liber DCCCXIII [813] vel ARARITA Sub Figura DLXX [570] Section 7 with one of her own hymns, Liber Elatio vel Lampyridae. The result is a hymn for two devotees who read alternating verses.

In the combined hymn, the two contributing hymns appear to dance around each other. Crowley’s contribution feels rather exalted, as it refers to “holy and formless fire” taken from the Chaldean Oracles, the repetition of which allegedly removes illusion, and the Hebrew term, “Qadosh,” which translates to “sacred” and “holy.” The journey here begins with the four elements and ends with an experience of the divine. Ms Feist’s hymn, however, begins with rather unpleasant visuals which lead to an ecstatic union. Her last verse is interesting:

“And the unutterable word that tears everything open And leaves bones for the vultures to pick.”

This suggests an experience akin to crossing the Abyss, where everything is disassembled, only to be reassembled on the shores of Binah. The combined hymn to me suggests an ascension experience aided by Typhon-Set culminating in the Abyss. Normally the adept is taken to the Abyss by their Holy Guardian Angel and then left to their own devices to enter and come out at the shore of Binah in the City of Pyramids. Perhaps Typhon-Set could be a companion who helps adepts cross?

The fourth hymn is quite erotic as Ms Feist builds on the ecstatic union in the previous hymn. She at first submits to her god, and then gives herself to him sexually. The challenging symbolism of a primate – reptilian union, easily expands to a union between a human and a god. One of her personal correspondences appears to be “The smell of lightning-driven ozone,” which is perfectly in keeping with the nature of a storm god.

In the fifth hymn, Ms Feist recognizes the presence of Typhon-Set in a violent overnight electrical storm, where the correspondence of ozone is repeated. The paradox of the storm is that even though it brings destruction, the rain fructifies the land and replenishes bodies of water, bringing about change in the process. Here at last we see the function of Typhon-Set as bringing about beneficial change in the guise of violence.

The sixth hymn builds on the fifth, with the realization that nothing is permanent, and change is inevitable.

The seventh hymn jumped out at me and it is the other combined hymn. Part of the verses come from the Bible, Job 41 (KJV) which is an outline of the power of Leviathan. While there are a number of descriptions of Leviathan in the Bible as well as in pseudepigraphal texts, the many-headed sea serpent description ties in neatly with Hesiod’s description of Typhon as having one hundred snake heads on his shoulders.

Interspersed between the verses taken from Job 41: 25-34 are the verses from Ms Feist’s Hymnus Inordinatio. This hymn basically pays further homage to the power of Typhon-Set / Leviathan and thus enhances the verses taken from Job.

The eighth and final hymn rams the point home that the essence of a devotional path is humility and submission, as it opens with:

“Dread master and lord

Cast your eye upon this child and servant.”

There are many more nuggets of gold in the hymns than I have discussed, and they will be picked up by eagle-eyed readers. Poetry allows for much more symbolism to be encoded than does prose.

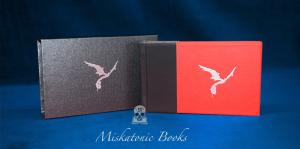

All in all, I can see Ms Feist’s text becoming a collector’s item for two reasons. Firstly, its presentation is magnificent. Secondly, Ms Feist distils two decades of magical practice into a serious devotional text. It is a deeply personal text which is a testament to Ms Feist’s courage in revealing so much of her own journey with Typhon-Set. Adventurous readers wanting to work with a powerful misunderstood deity in order to develop a mastery over change as well as accelerate their spiritual progress should seriously consider immersing themselves in this text and either follow it or use it as inspiration to craft their own path.

Tony Mierzwicki

Author of Hellenismos: Practicing Greek Polytheism Today and Graeco-Egyptian Magick: Everyday Empowerment.