“…And after the said Jane allighted and pulld the bridle of her head, and she and the rest had drawne their compasse nigh to a bridg end, and the devil placed a stone in the middle of the compasse; they sett themselves downe, and bending towards the stone, repeated the Lord’s prayer backwards.” Testimony of Anne Armstrong, 1673 [1]

Anne Armstrong was likely just a teenager when she became swept up in a dark cloud following the Newcastle witch trials that had taken place earlier in the century (1649-50), resulting in the execution of 15 women and one man. In the winter and spring of 1672-3, Armstrong gave a series of testimonies to magistrates, proffering remarkable detail of the diabolic meetings of witches. Historically significant as a rare description of the sabbat in England, it is unclear whether Armstrong was brought to account for these statements as no trial record survives following her deposition. That the sabbat and diabolic pact features in English accounts of the north-eastern corner of the country is unsurprising given the proximity and influence of Scotland over the region. As professor James Sharpe observed during a 2015 public lecture — a part of Newcastle University’s Insights Series — the ever shifting border of England and Scotland at Berwick was starkly demonstrated when the Ecclesiastical Court of 1599 tried a man for fornication and his wife of witchcraft. While the man was let off, the woman was burned at the stake across the border in Scotland.[2]

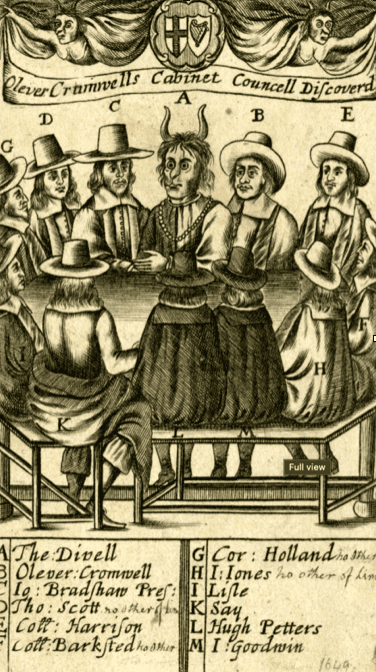

Armstrong’s name for the devil — Protector — may speak to the unpopular figure of Oliver Cromwell. Indeed, Cromwell was, after his death in 1658, widely rumoured to have sold his soul to the devil on the eve of the Battle of Worcester (1651). This legend holds that Cromwell made a Faustian deal for seven years [3] of good fortune, following which he died when the debt came due on the exact date that the deal had been agreed: 3rd September. Additionally, following the death of the Protector and restoration of the monarchy, Cromwell would be depicted frequently as the devil, or else an agent of Satan, in satire, poetry and image.

Another significant item within the deposition of Anne Armstrong is the use of the term ‘coven’, one of the few and earliest occurrences in English and Scottish witch trials. Religious upheavals would make words like covenant and conventicle familiar upon the English borders, perhaps giving us the communal ‘covey’, as it appears in Armstrong’s testimony, and the more familiar coven. Indeed, the word sabbat appears to be a relatively modern adoption in translation for terms more frequently attested in the historic record. Friedrich Spee, writing in 1631, like his learned contemporaries wrote in Latin and, therefore, favoured terms derived from conventus (meeting), from which English derivatives include convention, convent and, of course, coven.

Such testimony as Armstrong’s speaks to the inversion and antinomianism so prevalent in witchcraft history, and emerging from the troubled world of the early modern period of shifting and warring factions — both religiously and politically. The reference to reciting the Lord’s Prayer backwards — the Devil’s Paternoster — is a common trope found in such confessions from the late medieval period and is found mentioned as early as Chaucer.

…whiche wordes men clepen the develes Pater noster, though so be that the devel ne hadde nevere Pater noster…[4]

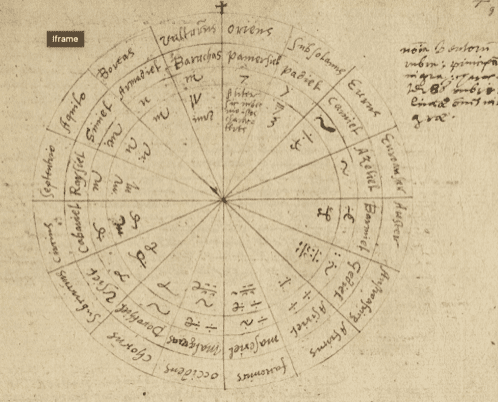

For now, however, what is most interesting in Armstrong’s rich and overlooked confession is the use of the term compass. The compass is well attested in learned magic circles (pun intended) and appears as a means of cataloguing angels, demons and spirits, including particularly within the Ars Theurgia Goetia. Additionally, the compass points — and incumbent spirits — are frequently and universally assigned to cardinal directions and seasons of the year. This evidence suggests that the modern ‘Wheel of the Year’ does, perhaps, have a logical and traditional place within sorcery and witchcraft, being built upon systems from at least the early modern period, if not the late medieval. However, it is sufficient to observe that, historically, we can identify spirit compasses in Solomonic spirit traditions dating to books compiled around the 17th century — coinciding with the life of Anne Armstrong. The Ars Theurgia Goetia is one of the books that constitutes the grimoire known collectively as the Lesser Key of Solomon and draws principally from Abbot Johannes Trithemius’ Steganographia (c. 1499). Indeed, so influential was Trithemius that his work is found in that of his students, Paracelsus and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, while Elizabethan court astrologer John Dee hand copied Steganographia for his own use.

The word ‘compass’ originates in Latin ‘compassare’ — from com– which signifies ‘together’, and –passus, meaning ‘step’. Therefore, the word compass in its original means to ‘step together’, or ‘pace as one’. From this, the idea of the length of a stride to measure an area — literally ‘pace out’ — provides fascinating insight into the use and function of the witches’ compass when combined with traditional and folk dances. Circle dances were popular throughout history, but often frowned upon by authorities and church alike. The most well attested form of dancing in a ring formation, often with linked hands, is in English the carole, accompanied usually by singing. It is from this choral dance that we derive our modern tradition of carolling, particularly at Christmas, except without the older form of circular dancing. Indeed, the word carole itself is Old French and denoted a type of ring dance. Other French terms for this style of medieval circle dance include ronde and rondel, commonly known to German-speakers as reigen. In Germany, the reigen dates from the 10th century, and was regularly denounced. The branle is a 16th century dance originating in France, but popular in Europe. In it, couples often alternate male/ female, linking arms or hands in a circle. A number of steps are danced in one direction, before reversing. Mentioned in Shakespeare, the branle was danced in the court of Charles II during the life of Anne Armstrong, being thought more popular than in its native France. [5]

In circle dances, as with the maypole at May Day fairs, there are two essential dynamics in play: a centre and circumference. In this way, ancient dances have always reflected an imitation of the movement and mechanism of nature through metaphor and allegory. In the medieval period, various attempts were made to define divinity, reaching an apogee in the high Middle Ages in a highly influential anonymous work, often attributed to Aristotle and Hermes Trismegistus among others. Liber XXIV philosophorum — Book of 24 Philosophers — is a theological text containing twenty-four aphorisms coined by supposed philosophers during a fictional universal gathering of wisdom. A relevant aphorism that is a most interesting when considering the compass and circle dances says that God, or nature, is

“… an infinite sphere, whose centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” [6]

A circumference may be defined as a boundary, or else an extremity that bounds a circle. Mythologically, we might understand such outer limits to be under the aegis of the god of boundaries, Hermes Chthonios (ρμῆς Χθόνιο), who both presides over and is able to traverse the worlds as psychopomp. For this reason, some of the earliest votary objects identified with Hermes were way-markers, often at crossroads, or else at the entrance to households, which defined the limit of territory and informed the journey from one state, condition or place to another. The herma, from which perhaps the name Hermes derives, was originally a pile of stones or cairn at a wayside, to which travellers might add their own as a votive offering for safe journey across borders. Eventually, the cairns were replaced with a plain pillar, with a male head at the top and sometimes genitals, as the god of the herma became anthropomorphised in the Hellenic world.

A boundary is often that which defines the extremity or limit that separates and distinguishes between that which is ‘this’ and which is ‘that’ — or ‘other’. Modern witches are fond of talking about liminality, and all true liminal spaces exist where boundaries delimit and demarcate, causing there to be a threshold which divides a state, condition or space from another — necessarily, that which is not the first position and is, therefore, other than. In terms of experiencing such threshold boundaries, these are often where we come up against that which is other than our individual perception and, as individuals, elect to encounter the world. What is meant by that?

We each project our vision of the world outward from an area occupied by where we imagine our head to be. In turn, we receive data through the five senses as to what is outside of us in the world-at-large. From incoming sense data, the brain or mind constructs an idea of the world encountered and accesses stored information to present a best approximation of what is experienced. This means that what we perceive is not the actuality but rather a summation contrived in the mind. This can be a daunting realisation to comprehend at first, and meditating on this is worth consideration. For exploration in experiencing the world from a position other than a location where we imagine our head to be, I recommend the work of Douglas Harding and his book On Having No Head.

All of this means that we may be able to get playful, mercurial even, in our interactions with the god of boundaries and how we meet the threshold of the world. We do this all the time in many small ways, such as socially. For example, in formal settings, we establish invisible boundaries and divide ourselves by a perceived stage, social cues, behaviours, etiquette, traditions, etc. Often, people say, if you are in an awkward or difficult circumstance, it helps to imagine the other people as being naked — a perfect example of being playful with how we choose to meet the world and adapting the boundary to are needs and desires. The circumference of our compass around us — physically, metaphorically, spiritually, socially — holds and sustains the boundary that divides us, or else lets permitted others in — gaining entrance by using correct passwords, ritual or acts that codify kind words, trusting behaviour or familial greeting. The compass is always present wherever we perceive our centre to be and represents the horizon or limit that we apprehend as a consequence, or else wield agency over through our own will.

When we work with the compass ritually, we are expanding that circumference and placing its perimeter in a more cosmic region extending out to the horizon to encompass a mythic landscape, and attendant spirits. In a holistic perspective, the circumference is ever expanding beyond the limits of the horizon — it is, therefore, expansive. In Thelema, this is the Goddess Nuit; feminine, pregnant potentiality — the cosmic womb and tomb from whence all comes, and to whom it must return. The centre, by comparison, is the counterpoint and complementary God Hadit; infinitesimal, everywhere fixed and shrinking to a fine point. In Islamic mysticism, this is the Qutub, the pole or axis which is pivotal.

In much of occult work, boundaries are established in the form of the magic circle. In Wicca, for example, the circle frequently serves one or all of three main functions — to protect, contain power and as a vehicle to move between worlds. All three require the circumference to be a relatively fixed and hard boundary; often emphasised by proscriptions and etiquette against how one enters, leaves, or the direction one moves. In Traditional Craft, the compass contrasts this when it opens the circumference outward as an expansive horizon to allow access to the landscapes and spirits who live there. It works on the principle that the world is “an infinite sphere, whose centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere,” and represents both a map and a cosmological model thereof. From the centre, we can choose to go out to the kingdoms at the edges of the horizon, or else invite them into our space as we will. By venturing out, we learn of the kingdoms at the compass edge and the occupying spirits. These have been mapped since the earliest times — the Liver of Piacenza is an ancient Etruscan compass with parallels in the Near East of antiquity. This model maps the world of the spirits through the chthonic and celestial realms as envisaged upon the horizon. It was used for augury, whereby a sacrificial liver could be studied and compared to the model and spirits identified.

There are many ways in which we experience our compass, which might be incorporated into our daily lives and not just our ceremonial, ritual or magical practice. The boundaries we establish, where they extend and what worlds they permit to cross over are within our power. It is up to us how we maintain those boundaries, and what words, acts, and ritual might be used to gain access. Similarly, when we are working with our compass ritually, it is incumbent upon us to divine the necessary codes and symbols required to access the other realms, and thus cross the boundary into the compass of the other. The ways of accomplishing this are myriad, and are accessible to all who would attempt such a sortie.

Footnotes:

[1] Transcription: Apr. 21, 1673, Newcastle-on-Tyne. (James Raine, ed. Depositions in the Castle of York Relating to Offences Committed in the Northern Counties in the Seventeenth Century (Surtees Society Volume XL, 1861): 197.) National Archives ASSI 45/10/3/34 – ASSI 45/10/55. [2] https://hauntedpalaceblog.com/2015/02/13/review-thinking-with-anne-armstrong-witchcraft-in-the-north-east-during-the-17th-century-by-prof-james-sharpe/ [3] Later proponents of the Witch Cult theory of the twentieth century espoused the idea that the sacred king sere for seen years, following the work of Sir James George Frazer — see Rex Nemorensis in Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890-1915). [4] Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales in Plain and Simple English. BookCaps, 2012. [5] Scholes, Percy A. (1970). “Branle”. The Oxford Companion to Music, tenth, revised and rest edition, edited by John Owen Ward. London and New York: Oxford University Press. [6] The Book of the Twenty-four Philosophers. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.themathesontrust.org/papers/metaphysics/XXIV-A4.pdf.

The Witch Compass: Working with the Winds in Traditional Witchcraft

The Witch Compass is Ian Chambers’ first book, published in 2022 with Llewellyn, and is available through all good booksellers. Signed copies of The Witch Compass are available from the author’s website: surrey cunning.co.uk

Explore the compass of the eight winds, a magical circle at the heart of Traditional Witchcraft. More than a tool for protection or raising power, this framework provides the ritual means to traverse the worlds and a mythic landscape that can be accessed at any point in time and space. Traditional Witch Ian Chambers teaches how the Witch Compass represents an entire worldview, a cosmological map, and a method for magic and revelation. He helps you develop your own compass and use it for divination, spirit work, and practical sorcery. This book shows you the world through the lens of your Witch Compass and reveals the many realms and spirits available to you.

“With this invaluable book, the aspirant unto traditional Craft and the seasoned practitioner alike are carefully guided through the workings of the compass as the map, via which the Crafter may traverse magical realities, encounter spiritual presences, and commune with ultimate Truth.” – Gemma Gary, author of Traditional Witchcraft, A Cornish Book of Ways.

“A scholarly, inspiring, and eminently informative work. I give it my highest recommendation.” – Lon Milo DuQuette, author of The Magic of Aleister Crowley.

“I found this a most fascinating and informative book, describing as it does the rationale behind the actual working of the compass, with plenty of practical demonstrations and exercises to enable the reader to experience the compass for themselves…This is a sorely needed book that gets to the heart of the inner workings of the compass and provides a wealth of most valuable material for both the beginner and more experienced practitioner alike. I congratulate Ian on producing an approachable and understandable book which will add greatly to the sum of available knowledge on a sometimes obscure and difficult subject.”―Nigel G. Pearson, author of Treading the Mill.