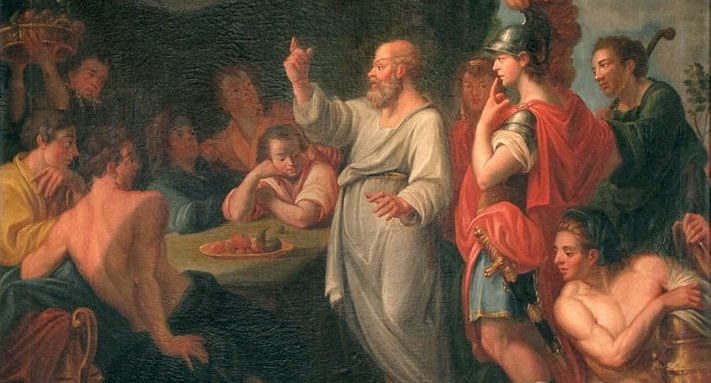

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses we find the story of Baucis and Philemon, an older married couple living in what is now modern-day Turkey. Ovid tells us that the couple were old and poor, but kind, and that when they were visited by two peasants, Baucis and Philemon welcomed the two strangers into their home and shared with those peasants all they had to offer. In the middle of dinner Baucis noticed that the pitcher she was pouring wine from seemed to magically refill on its own. Knowing that only the gods were capable of such a miracle, Baucis and her husband then fell to their knees in supplication and offered all they had to the deities seated before them.

Impressed by their generosity and piety the now revealed Zeus and Hermes tell the couple to journey with them to the top of a nearby mountain, because Zeus had decided to destroy the town they lived in. For only Baucis and Philemon had offered the gods shelter, food, and drink on their journey, and the town needed to suffer for its wicked ways. After reaching the top of the mountain Baucis and Philemon looked back and saw their town now underwater, but where their house once stood, was now an ornate temple. Baucis and Philemon asked the gods if they could serve as clergy there, and their wish was granted.

But the gods were not done bestowing favors upon the couple, and Baucis and Philemon had one last request: to die together. Many years later after serving the gods in their temple, Zeus honored the couple’s request and they were transformed into a pair of intertwining trees so they could spend eternity together.

The story of Baucis and Philemon was the first thing to enter my mind while reading the Rabbi David Wolpe’s poorly considered piece, The Return of the Pagans in The Atlantic.* Like many monotheists Wolpe is convinced that his religion’s cosmology is the only correct way of thinking, and that monotheism is superior to other creeds.

Part of my dislike for Wolpe’s piece is just how lazy it is. It seems that it never occurred to Wolpe that there might be self-identifying Pagans living in the world today, and perhaps even some Pagans who might read his words. There are probably at least two million self-identifying Pagans in the United States alone, as a religious minority himself, this just feels like something Wolpe should know.

Wolpe also never takes the time in his piece to adequately define “pagan,” a must when considering such a complicated word. He makes a few half-hearted attempts:

Most ancient pagan belief systems were built around ritual and magic, coercive practices intended to achieve a beneficial result.

Although paganism is one of those catchall words applied to widely disparate views, the worship of natural forces generally takes two forms: the deification of nature, and the deification of force.

Neither of those definitions are adequate, and in many ways both are completely wrong. (Pagan) Roman emperors outlawed magic at various junctures and I’m not sure how honoring the Winter Solstice might be considered “coercive.” I’ve also never quite figured out why using magic to achieve a desired outcome is wrong, but using prayer to do the same thing is not?

Most of Wolpe’s piece argues that the politics of the left is concerned with the “deification of nature” and the politics of the right are concerned with “the deification of force,” ideas that Wolpe believes are “pagan.” We have certainly been led to believe that our pagan ancestors revered nature, and some of them certainly did, but the vast majority of them were probably most concerned with simply getting by. Ancient pagans littered, clear cut forests, and did lots of other things that are far from the “deification of nature.”

Wolpe contextualizes the “deification of force” by writing that it is seen as the desire for “wealth, political power, and tribal solidarity” ideas which he links to idolatry. But again I’m confused why these are pagan values, and not simply human wants. Paganism both then and now was a complex thing (paganisms has always been more accurate), which means there were pagans craving power and other pagans who simply didn’t care about such things. Because these desires are human ones, they can also be seen in the Bible, but because “monotheism” is superior in Wolpe’s view he deems it best to ignore stories that don’t support his narrative.

Instead of embracing the wisdom that can be found in the writings of Classical Paganism, Judaism, and Christianity, Wolpe insists one is completely unlike the other two:

“The Greeks taught that the rich and powerful and beautiful were favored by the gods. Then along came Judaism, and after it, Christianity, arguing that widows and orphans and the poor were beloved of God.”

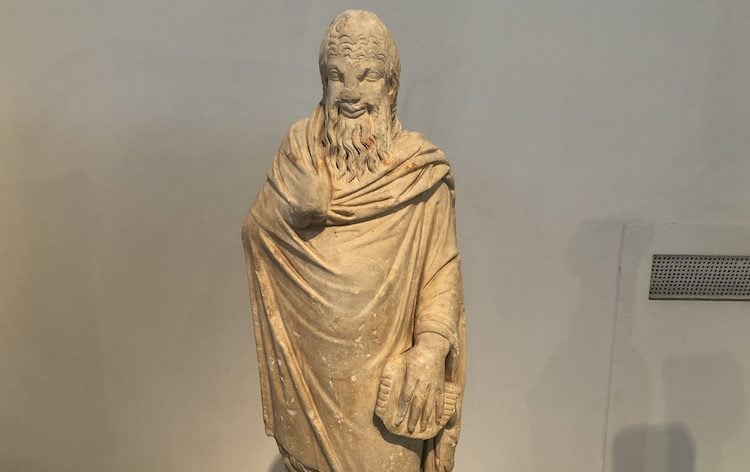

And yet Zeus and Hermes found much to love about Baucis and Philemon despite the couple being both poor and no longer beautiful. When Pan was born the other gods delighted in the site of him, despite the goat-god being born with hooves, horns, and the legs of a goat. (Pan then went on to live in a cave in Arcadia, so much for wealth!) It’s true that Ancient Greek and Roman societies were often cruel, but so were ancient Jewish societies, and the Roman Empire didn’t get much better after its conversion to Christianity, and probably regressed.

Despite the best efforts of many different teachers and philosophers over the millennia, there has always been a subset of humanity incapable of receiving a message of love and tolerance. That refusal to listen is not the result of “paganism” but instead seems to be a defect in human nature. It’s easy to see humanity’s awfulness in figures like Elon Musk and Donald Trump (two figures that Wolpe of course links to paganism), but those types of individuals are the exception and not the rule. There are a great many more of us who do care about others and do have empathy for others.

Towards the end of his essay Wolpe attempts a reflective and inclusive tone:

“Monotheism, at its best, acknowledges genuine humility about our inability to know what God is and what God wishes, but asserts that although human beings are elevated above the shackles of nature, we are still subordinate to something greater than ourselves.”

And fails. Ancient pagans most certainly did the same thing. That’s why millions celebrated the mysteries of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis, honored Hekate at the crossroads, and gathered in secret to worship Dionysus. Ancient pagans knew that there was something greater than themselves in the world, and took the time to seek that mystery. The ecstatic rites of the ancient world were an attempt to know the gods.

There is almost a nice moment at the end of Wolpe’s essay when he nearly stops blaming ancient paganism and atheism for the world’s trouble, but then he can’t help himself:

“But if we are all children of the same God, all kin, all convinced that there is a spark of eternity in each person but that none of us is superhuman, then maybe we can return to being human.”

We are all kin, children of the same earth, and within each of us lies a spark of something truly divine. But the humble person is smart enough not to dictate the gods/god or creed a person might (or might not) worship. For I am not the child of your “God” in much the same way I would not claim you are the child of my gods. I am all for a universal return to being “human” but that will be hard to do alongside Wolpe as long as he continues to preach that my beliefs are wrong and only his are right.

*This link will take you to the Atlantic’s website, which is currently something many of my friends are opposed to. I am a subscriber to The Atlantic, and think they have published many thought provoking pieces over the last several years, along with some truly great journalism. Sadly, Wolpe’s article is not among those articles worthy of praise. I have always valued the Atlantic for publishing a wide and diverse array of voices. You can also read a version of the article on question outside The Atlantic proper by clicking here.