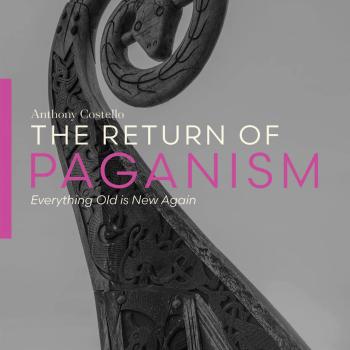

Recently, I posted about a new eBook I wrote on the return of Paganism in America (actually, in the West more broadly). That book can be found here for those interested in the topic. To my surprise one of my co-bloggers here at Patheos, John Beckett of “Under the Ancient Oaks,” graciously purchased a copy of the book, read it, engaged with its content, and even found the time to write a short review. What follows is my response to John’s critique of the book. I will take each of John’s critiques point by point. But first, a word of thanks.

Preface: Thankful for The Review

First, let me simply state I am thankful to John for taking the time to read and, for the most part, fairly represent the book. I should also say, as John notes, this book is really more of a pamphlet, and cannot be confused with a full-length or comprehensive treatment of the subject. The ministry that published the booklet, Ratio Christi, is an Evangelical campus Apologetics ministry and had asked for a compact 9,000-word piece on Paganism. My original draft clocked in at closer to 13,000 words, so much had to be cut out in the editing process.

That said, a longer, more comprehensive and more rigorously-argued book is in the works. This booklet is more of a “highlight” reel of what is to come, each section requiring an entire chapter to treat the topic sufficiently (then again, can any topic, especially one so broad, ever be treated sufficiently?) Nevertheless, I appreciate John’s engagement and his opening remarks regarding my other writings here at Patheos.

Point #1 It’s a Good Review, For the Most Part

Second, John treated the book fairly, even if I have some counterpoints to make in response. Part 1 of my booklet was aimed at simply describing neopagan thought and practice as accurately as possible. To do this, I drew from an academic text, The Handbook of Contemporary Paganism, published by Brill and edited by two practicing neopagans: Murphy Pizza and James R. Lewis. One of the things I learned in seminary is to always deal with the best primary sources one can find on a topic. I tried to do that here.

For Christians interested in engaging intellectually with Paganism, or contemporary Neopaganism, I would recommend dealing with the authors and essays in Pizza and Lewis’ edited volume. In particular, I found the work of Michael York most engaging and rigorous. York also has two monographs worth looking at: Pagan Theology, and Pagan Ethics. Unfortunately, his book on Pagan ethics is categorized as an academic textbook and is quite expensive. As such, if you are interested in this topic, a trip to the library might be warranted.

Later in John’s critique he mentions that my book was not meant to “convert pagans,” but to “stem the tide of people leaving Christianity,” and “close the barn door.” He also suggests that the book isn’t written for those who “aren’t in high school anymore,” and who can “spot fallacies.” Before getting into the more substantive points about pagan ontology, epistemology and ethics (or whether there is one), let me address these claims about the project of the book itself.

First, it is true that the book was not written to pagans, or for a pagan audience. As such, it is not an attempt to convert pagans (I would only do that face-to-face anyway, given my understanding of “witnessing”). It was written primarily for a Christian audience to elucidate the kind of paganism Christians will find themselves butting up against with greater frequency in the present day and near future.

Second, the book was intended for an 11th-grade reading level. So it was simplified to make it comprehensible to a wider audience. That was not my choice, but it is what I was tasked with. My original draft had to be edited quite a bit, the editor saying initially that “only someone with a Master’s degree” would understand it. While that wouldn’t excuse logical errors, I will show in a moment that there were no actual logical errors present in the text.

Point #1(b): A Word about Pagan and Christian Evangelism

Finally, as far as Christians leaving the church, this is simply not a major concern of mine. As someone who lived as a Roman Catholic, then as a “spiritual but not religious” quasi-pagan (I would have called myself a universalist of sorts, with a bent on religious syncretism and a penchant for belief in reincarnation), and now as an Evangelical Christian, I leave the coming and going of people into and out of God’s Church in God’s hands. In fact, Jesus Himself commends us to do just that (cf. Matt 13:24-29). Numbers don’t concern me. What concerns me is truth.

Thus, even if we see the Church in the West losing numbers, that is no argument that it is on account of belief in some form of neopaganism. The Neopagan would have to make an argument for that, most likely one grounded in empirical data. Further, the Neopagan should also not ignore or marginalize former neopagans who are becoming Christians. For other examples of this see here and here. That said, I do acknowledge in the book that neopaganism is growing.

In this sense, given John’s apparent desire to see the world become more pagan, and to even evangelize for Paganism, we both stand in similar positions. John, after all, says this in his review, commenting on my point that I believe the culture we live in is already pagan:

I wish he [Costello] was right.

I wish we didn’t have states mandating the Ten Commandments be posted in every public classroom. I wish Beltane was a national holiday, and that we all celebrated the Winter Solstice instead of Christmas. I wish an American President was Pagan…

Perhaps the main difference between us on this question of evangelism to a “non-believing” culture, is that I am less concerned about it given my absolute belief in the sovereignty of God as far as who ultimately winds up in or out of His kingdom. That simply isn’t up to me, and I thank God it isn’t.

Alternatively, consider what the opposite belief might lead to (and, to be fair, has lead to in the past), if conversions are really up to human beings. This is one reason why the thought of a truly pagan culture is a bit upsetting. For I might rightly raise the question of what restrains the neopagan in their pursuit of converts? What is off-limits, so to say, for the Pagan evangelist, and why? I think for the Christian, there is legitimate concern that anything is restricted on paganism.

Point #2 On Pagan Ontology

As far as ontology is concerned, John seems to say that I basically get it right: Paganism is, or paganisms are, pantheistic when it comes to ontology. Paganism has a metaphysically monistic view of reality: all is one, and all is god. The Creation-Creator distinction that the opening salvo of Genesis, the Mosaic Law and Paul’s first chapter to the Romans make so explicit and crucial evaporates on any pagan worldview. As Michael York puts it succinctly “Matter is mater” for the neopagan. John seems to want to go a more animistic route, perhaps, but there is little criticism of my explication of pagan ontology.

That said, what I did not have time to cover in the book, but which will be relevant to the argument against neopagan metaphysics, is the problem of the eternal universe. It seems to me that if the universe is finite, and if finite contingent, then the neopagan has a real problem for his view. In fact, I think the neopagan has a defeater for his view if it can be shown that the universe is not eternal, but is past finite and, as such, came into existence.

In my longer work I will be using arguments from analytic philosophy and from contemporary scientific discoveries that I believe demonstrate the Universe is not, nor even could be, eternal in the past. For one recent exposition on the finitude and contingency of the universe, i.e., of Nature, see Stephen C. Meyer’s book, The Return of the God Hypothesis, or our interview with Meyer here. Once you have an immaterial, agent-like Mind that brings matter into existence, neopaganism is no longer a plausible candidate for rational belief (let alone worship). Speaking of rational belief, this leads to epistemology.

Point #3 Pagan Epistemology

As far as pagan epistemology is concerned, John says the section was “honest but incomplete.” Again, with a 9,000-word limit I wholeheartedly agree about the incompleteness. What struck me most, however, about this part of John’s review was that he did not quote the account of the pagan experience I use in the book: experience being the primary, and perhaps only, candidate as a source for justified, true belief on a pagan worldview.

Perhaps John felt that that account, of one “Jo Crow,” was either not representative of pagan experiences in general, or perhaps he was worried that it might undermine his own project of pagan evangelism? I don’t know and can only speculate.

But, for the reader of this article, let me re-present the testimony of Jo Crow, who underwent the “Wild Hunt Challenge,” a pagan event held in Norfolk, England:

Wolf came inside me. It was terrifying. He was right in my face, standing on his hind legs staring at me face to face . . . I smelt his breath; his fangs were dripping. He was going to devour me. He said, “You have to let me in. You let me in once before.” On another occasion, in a dream I had mated with wolf on a village green. It was an ecstatic and wonderful experience. He showed me this dream and, although I was quivering with terror, I allowed him in. He came behind me and went into me at the base of my neck. I became filled with wolf and went on the Hunt. I ran with the Wild Hunt and I went on the rampage. I was taken by the Hunt.

When I came off the downs, one guy could see that I was not out of wolf and tried to bring me back. He joined his forehead to mine to try to call me back but wolf came out of me and almost bit his head off. Eventually I went to bed and I still had wolf in me and every time I looked in a mirror I saw wolf. I still had wolf inside me and came back down later. Sometimes he comes as a companion but does not sit inside me. Wolf helps me to walk in two worlds.

Susan Greenwood, “The Wild Hunt: A Mythological Language of Magic,” essay, in Handbook of Contemporary Paganism, eds. James R. Lewis and Murphy Pizza (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 214–215.

I will let the reader discern for themselves whether they think experiences of this sort are: a) a rational way of knowing whether something is true, and b) whether or not it is even good to pursue such experiences, especially given what we know about the cognitive structures of the mind, and the fragile nature of our mental health.

John goes on to say that I do not offer a better epistemology, and, admittedly, there is short shrift about why Christianity has better epistemic resources than paganism. However, in brief, I would point to the long, and relatively exalted, history of Christian natural theology, as well as Christian historical apologetics as areas of rational discourse that do a much better job at articulating reasons to believe than the ecstatic experiences of the neopagan practitioner. For more on this, one can access my articles here, here and here.

To be blunt though, I must say I find it hard to even compare pagan experientialism with something like Thomas’ Summa Theologica, or, more recently, works by the likes of Swinburne, Plantinga, Pruss or Koons. For more on epistemology in general, as well as religious epistemology, also see here.

Point #4 Pagan Ethics

As to his comments in defense of a Pagan ethics, I fear John makes a simple, yet common error. He takes me, I think, to be arguing that Pagans cannot be moral, or that they cannot say moral things. But that is not the argument I make in the book. The argument is that an appeal to Nature alone, to include human beings who, on the neopagan account, are products of the stuff of nature (which is, of course, partially true) is not sufficient to ground moral values and duties.

Thus, while the Wiccan may say “as it harms none, do as you will,” and Aleister Crowley preach “love is the law, love under will,” they have nothing to ground those moral claims in, let alone define them, other than the will. But whose will? Answer: their own. In his classic critique of Nominalism, Ideas Have Consequences, Richard Weaver referenced Shakespeare to clarify the problem:

Have we forgotten our encounter with the witches on the heath? It occurred in the late fourteenth century, and what the witches, and what the witches said to the protagonists of this drama was that man could realize himself more fully if he would only abandon his belief in the existence of transcendentals….The issue ultimately involved is whether there is a source of truth higher than, and independent of, man; and the answer to the question is decisive for one’s view of the nature and destiny of humankind.

quoted in R. Scott Smith, Exposing the Roots of Constructivism, 5

But, this is where the neopagan runs into a real problem, as I present in the book. What about immanent nature tells me whether an action is loving or not? When a male shark forcibly copulates with a female shark, does that tell me anything qualitative about love? Does it define love for me? How so? When a certain species of praying mantis eats it mate, what moral fact does this compel me to accept or deny? Further, it matters not whether we go up the food chain to include human animals in this equation. Again, on pagan ontology, “all is one” and “all is god:” you, me, the great white shark, the praying mantis, etc. John seems to agree with me on that point.

So, who is to say, or judge, over whether or not these actions by “lower” animal forms are qualitatively any different with regard to their moral value as the actions of any other animal, human or not. If nature is shot through with divinity, and there are not qualitative hierarchies, then what nature does is just what nature does. This is a real problem when it comes to social behavior, something that Mattias Gardell surfaces in his chapter in Pizza and Lewis on “Wolf Age Paganism.” After all, perhaps John desires to adopt some form of “love” ethic, one that respects the autonomy of persons or other people groups. But who is to say that the Wolf Age pagan who adopts a form of ethno-paganism, rooted in a sense of racial superiority, is wrong given a pagan worldview devoid of a standard higher than man?

Of course, for the astute observer, the real issue here is that of nominalism versus realism, or essentialism. However, and I think John knows this, if the neopagan adopts a kind of essentialism, say Platonism, one that posits abstract, immaterial objects as the grounds for moral facts, then one has already undercut the primacy of the material. This has the potential then to morph into something like a neoplatonic worldview, one that most neopagans would reject, on account of York’s maxim that “matter is mater.” Platonism, being one step closer to theism, is a step most neopagans would see as a bridge too far.

As such, my same critique would apply to a more specific area of morality, like sexual ethics. I think John and I would be in agreement that sex is “good and natural.” After all, I would argue God made it, and, as such, it is good! That said, that anything good outside of its proper context can become something not good is evidenced by many things in nature. A delicious Porterhouse steak can be genuinely good. But, if eaten by someone with high cholesterol levels and a high risk of heart disease, or if eaten in front of a starving refugee from a third-world country, the eating of the steak can quickly become an immoral act. Thus, whether or not consent alone is a sufficient condition to make sexual intercourse good is, at least, questionable, even on a non-Christian worldview.

Point #5 Christianity and Paganism: Two (Very) Different Paths

Here John quotes the book accurately “Paganism and Christianity cannot really co-exist in any meaningful way, in spite of their shared humanity.” As far as it goes, this is a true statement. John thinks it a “dangerous one,” at least prima facie. However, this clearly does not mean that we cannot live in the same place or in the same culture in a relatively congenial way with one another. What it does mean though, is that on the most basic, most fundamental and most profound questions of existence we will never see eye-to-eye. The belief systems are simply too diametrically opposed to have, what we might say in Christian lingo, “real fellowship.”

Further, this lack of agreement on the most foundational issues will have obvious affects on our attempts to live together. For example, we will more than likely not see things in the same way when it comes to politics and what kinds of policies should or should not be promoted. Of course, there may be some overlap, but one would imagine real tension in the political realm between the average pagan and average Christian (Catholic, Protestant or Orthodox). So, can we be “polite neighbors” as John suggests? Absolutely! And perhaps even more than polite, we can be kind to one another. Minimally, I can say with confidence that the Christian is commanded to be so and, if he or she really cares about what God says, will also do so. That said, however, there is difference between being kind and being accepting or affirming.

That said, where I think the real danger lies is in where contemporary pagans wind up taking their Paganism. As I also point out in the book, the real gods of Rome were not Jupiter, Mercury and Mars. Rather, the real god of Rome was Rome. The serious issue, as I see it, has to do with what kind of Paganism ultimately wins out in western society. Is it the kind of Paganism that simply wants to reconnect with nature, that shuns modern technology, that wants to “turn on, tune in, and drop out” of the contemporary political process, the global economy and the technocratic state? Or is the kind of Paganism that seeks to synthesize its spiritual power with the global economic forum, the power of the state and the looming threat of a totalizing technology (e.g., the AI demonic)?

Or, is a Paganism that is happy to practice its dark arts, ones that include all those things that the Bible refers to as “abominations,” imminent? These developments in neopaganism will matter.

Christianity has been the most “synthesizing” religion in the history of the world. It can bring many religious features under its wings, to include many pagan features, and elevate them in and through the revelation of Jesus Christ, and this in spite of the many sins and atrocities of its adherents over the generations. Whether Paganism, however, can in any meaningful way make room for Christianity is, at best, unknown, although historical precedent suggests it is unlikely. For when Christianity was at its best, in the sense of having the least to do with worldly power, Paganism was not kind to it: the Cross and the Lion’s den are testimony to Paganism’s in principle stance against a transcendent God, a transcendent Law, and those who proclaim them.