This is a piece on how the practice of Zen Buddhism can support and sustain a person on the journey of recovery.

So to begin, how might we define recovery? The term “recovery” is increasingly used in connection with healing from mental illness, but it is perhaps most commonly associated with overcoming addiction to Alcohol and other drugs, as in my case. I hope to relate recovery to not just overcoming addiction to substances, sex, food, etc. but to overcoming anything that may be pulling you away from your life as it is in this present moment.

In approaching this subject I wasn’t sure what course to take. I thought it would be easy to start at the original turning of the wheel of Dharma. When the historical Buddha first taught the Four Noble truths and the Eightfold Path. It would jive nicely for those in the crowd that might be 12 steppers. Four Noble Truths, an Eightfold Path? Equals 12 too! But than the other consideration was how do I express how this practice has enhanced my own recovery. How has it supported and sustained me in the journey of recovery. And why a religious practice has much to offer in our contemporary times.

I will try and do both.

So let’s start with the other 12 steps:

In his first sermon, the Buddha said, “I teach one thing and one thing only: suffering and the end of suffering,” He then went on to outline the Four Noble Truths. Shorthand these are:

- There is suffering. (Dukkha)

- Suffering has an origin.

- The cessation of suffering is attainable.

- The path to the cessation of suffering.

According to Kevin Griffin who wrote one of the seminal books on Buddhism and Recovery titled One Breath at a Time, writes these Noble Truths can be translated as such:

- While some elements of life are inevitably painful, like getting sick, getting old, and dying;

- Many of the difficulties we experience are created by our own tendency to crave pleasure, avoid pain, and cling to that which can’t be held.. (impermanence)

- Nonetheless, if we see these Truths and how they work, it’s possible to break pattern and achieve joy and freedom;

- The way to achieve this freedom is by following a practical set of guidelines for life and spiritual practice.

The Buddha says that the appropriate response to the first noble truth is to understand suffering. For the person in recovery this Truth is embodied in our understanding of our addictive suffering, and thus begins our recovery process. Until we see the deep and profound unsatisfactoryness of our addictions there is little possibility of change.

This understanding challenges us to think of the real-life difficulties we face. Difficulties that just come with being human. It asks us to consider all the other people who share the same forms of suffering. Maybe we will see we are not alone in our difficulties and pain.

It also challenges us to think of the ways in which we create or exacerbate our problems through clinging or rejecting.

And regarding our addictions, It asks us to look at all the ways our particular addictions have created suffering in our lives. To consider all the ways our addictions have caused you and others pain.

Kevin Griffin also says that the Second Noble Truth makes clear that our suffering is caused by our craving and clinging. This unsatisfactoryness is feed by our constant longing for things to be different from the way they are, our sense that things are never right. In fact, for many of us, removing the obvious addictions only reveals the tendencies beneath them, and we discover that we cling and cause ourselves suffering in all kinds of ways.

The Buddha said that the wise response to the second noble truth was to abandon clinging. Ultimately, that is the task of all spiritual work, and the task of a lifetime.

The Third Noble Truth states that if clinging causes suffering, letting go brings relief. (it’s actually more than that but..) Griffin says that in the 12 steps this is step two. The Third Noble Truth and the Second Step both relate to the awakening of faith on the path.

The Buddha said that the wise way to respond to the third noble truth is to realize it. When we realize that suffering and addiction can end, we are inspired to stick on the path.

Now to the Fourth Noble Truth. The Buddha said that the wise response to the fourth Noble Truth was to cultivate it. Both the 12 steps and the Eightfold Path give us frameworks for this process. Either one is a relinquishment of ego, or preferences and reactivity, a turning toward a set of wise, guiding principles. The Eightfold Path is the path the Buddha taught for moving towards freedom.

For the sake of time I won’t spend much time here but would encourage you dive deeper into the eightfold path when you have time. But in a nutshell the Eightfold Path promotes three essentials of Buddhist training and discipline

- Ethical Conduct – Right speech, action, and livelihood

- Mental Discipline – Right effort, mindfulness, and concentration

- Wisdom – Right thought and understanding

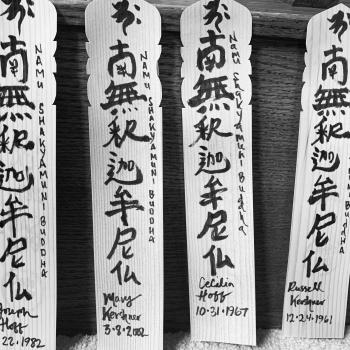

Now time for my own story. I entered recovery at the age of 26. I discovered meditation shortly thereafter. A friend in recovery had discovered that I was having trouble sleeping. At the time, I had a bad case of “monkey mind.” I could not fall asleep without the radio on. I needed something to drown out the noise of early recovery. So, one night this friend pulled me aside and said, “I think this will help you.” He handed me a cassette tape (yes, it was a while ago) and on one side of the tape was a meditation instruction, and on the other, a guided meditation. I started to listen to the guided meditation religiously. It was just a matter of time before I no longer need the radio on to fall asleep. I was hooked.

I continued the meditation practice but found myself wondering if I was “doing it right.” This led to me going on a journey of visiting various meditation teachers and religious practices. I started with a Vedanta group, then a Tibetan Buddhism group, then a Theravada group. This journey eventually led to me visiting a Zen group. It was in Zen where I found my “home.” I have been practicing Zen ever since.

So now I thought it would be helpful to pull together a list of things I have found so valuable in Zen practice and that has supported my recovery. I mean there’s always a list, right?

Let’s start with:

Boredom. In my work in addiction treatment one of the number problems that would pull people off the course of recovery was boredom. Nobody knows how to do boredom anymore, especially those in early recovery. Once living a life of extreme highs and lows, recovery, early recovery especially, bring about the scary experience of boredom. The practice of distractions diminishes, and we experience our lives as they are. Scary stuff! This practice has made boredom possible for me. By offering opportunity after opportunity to let go of wanting life to be different than it is. To feel the feelings, and to let them come, over and over again. Now, or most times, boredom isn’t something I’m afraid of. I’m not in such a hurry to run away from myself anymore. And for this I am grateful.

The idea that In Zen there is nothing to attain, or that Zazen is good for nothing. This teaching has helped me to stay grounded in recovery. Theologian Paul Tilich wrote of the need to replace the unbroken myth with the broken myth. What this means to me is how often, people who struggle with addiction can fall victim to moving from one unbroken myth to another unbroken myth rather than lean into the uncomfortable uncertainty of the broken myth of our lives in recovery. Folks who struggle with addiction are prone to go find the next shiny thing. And bounce form shiny thing to shiny thing. Hoping the next thing will make us feel better and relieve our suffering. This teaching points to where the real gold can be found. In the imperfections of our lives, relationships, communities, as they are right now. That we will be a lot better off if we stay put and lean into the brokenness of our paths. This teaching attempts to break you of any expectations from Zen right from the start. So that maybe you can settle in for the long haul, of the great matter of life and death.

Zen practice supports us through the inevitable heartbreak of recovery. The experience that drove me into an actual student teacher relationship in Zen is a story of loss. Several years ago now, I had a friend in recovery. We would meet regularly at my kitchen table, and discuss recovery, and support each other in the process of recovery. One Sunday night when we were supposed to meet, he called me and said he had to reschedule. I thought nothing of it at the time and said no problem. That I would see him tomorrow. When I went to the location where we suppose to meet the following day, I found out he had taken his own life earlier that day.

This wasn’t the first loss I experienced in recovery. But this loss, for some reason, broke me.

It was a broken heart that deepened my Zen practice.

Grief and loss are part and parcel of a life in recovery. And how we meet these challenges have great influence on our lives and recovery.

“I have never questioned, as a Buddhist, how active I should be in the world. I suppose because I came at this from another direction: I was already active in a world that was breaking my heart. I became Buddhist so that I could stay in this world and allow my heart to keep breaking.”

— Margaret Wheatley

Zen teaches us how to sit in our soup of suffering. If we’re in recovery (and if we’re not) we probably have much experience with trying to reduce suffering in our lives via practices that paradoxically invite more suffering into our lives. In the grip of avoiding suffering we often create more suffering. Ruins upon ruins. It’s a vicious circle. What Zen teaches us is how the fear of suffering is ultimately more terrible than the suffering itself. We discover this through the revolutionary practice of sitting in our soup. Over and over again. And somehow, I’m not sure how it works, but over time, if done with great determination, suffering gets transformed.

Zen & Trauma. The first multi day Zen retreat I went on was before I was ever a therapist. During the second day of this retreat the women who had been on the cushion next to me for a day and a half started to weep. And she wept. And we all sat holding that space for her. It was then I discovered something about the power of this practice. As we do it together. There’s a lot of talk in therapy circles about holding space for our clients. Creating an environment of safety so that we may look at the light and shadow of our lives. But it was there at a Zen retreat that I first saw the power of what might happen in this sort of space. Rumi writes, “The cure for the pain is in the pain.” Buddhist psychologist Tara Brach writes that the path of befriending our experience requires great gentleness and patience, as we learn to meet whatever arises in our body, heart and mind. Zen practice has allowed me to find the gentleness and patience to do the work of examining my own trauma. And in this effort, I have been awarded glimpses of the awareness and love that are our true essence.

The Bodhisattva Vow and Helping others who struggle. As someone in recovery I am encouraged to continue to try and help others struggling with the same addictions that I have struggled with. That in helping I receive help. That I am uniquely qualified to help. At the end of todays talk we will chant the Four Great Vows, otherwise known as the Bodhisattva Vows. We will start this chant by vowing to save all beings. Will I be able to “save all beings?” Not likely but that’s not the point. Robert Aitken Roshi says that chanting these vows cultivates bodhichitta — which is the aspiration for wisdom and compassion, and the determination to practice it in the world as best I can. I appreciate these regular reminders this practice brings, as I toil in the often-difficult task of working with others on the path of recovery. It sustains this Bodhisattva practice.

Ground in Groundlessness. That friend I told you about that introduced me to meditation via the cassette tape, also said something to me that was very important, very early in my recovery. One night he told me, “Chris, you better learn to get comfortable in the grey.” Now at the time I didn’t know what he meant, but I knew he just told me something important. I have since come to understand that he saw in me what I know often see in others. The desperate desire for the world to be black and white. But the world isn’t black and white. It’s a whole lot of grey. Especially in the adventure of recovery. If Zen practice has taught me anything, it’s how to lean into the uncertainty of life. It has gifted me ground in groundlessness.

Zen as a guard against Isolation. As a mental health clinician, I have come to learn one important fact. That no matter the problem. It grows in isolation. This is especially true of addiction. Although a seemingly a solitary activity, Zazen or Zen meditation, has awakened me to the great fact of the interconnectedness between all beings. That we are all a part of the greater whole. This practice has dissolved for me the great lie that I am on my own. Alone in this scary world. And that in this interconnectedness lies a great many possibilities for connection. There’s a great Ted Talk out by the social scientist Johan Hari where he says that the opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety, but rather connection. If given time and effort, this practice will make that abundantly clear.

And finally, the Sangha. There’s a favorite sutra story of mine where Buddha’s right-hand monk Ananda came to him to share a new understanding

Ananda, asked the Buddha:

“Lord, is it true what has been said, that good spiritual friends are fully half of the holy life?”

The Buddha replied, “No, Ananda, good spiritual friends are the whole of the holy life. Find refuge in the sangha community.”

And that my friends, is why I keep coming back to this practice.