Back in 2006, I was a new father and was in the final stages of my dissertation on occult initiation rituals. My hermetic magickal group had just broken up a few years prior and I was publishing articles and book chapters on comics, Buffy, and other pop culture items. I was in the movie theater seeing the new Darren Aronofsky film, The Fountain, starring Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz. At the time, Aronofsky was relatively fresh off the success of his disturbing but groundbreaking indie classic, Requiem For A Dream. My interest in Aronofsky, however, was based on my love for his debut film, the black and white exploration of numbers, Kabbalah, and obsession, Pi.

For me, having recently lost some important people in my life, and still traumatized by the birth and three month struggle for survival of my severely premature daughter (now a 1st year college student), I was emotionally vulnerable watching a movie about death, loss, grief, and hanging on too long. I remember my experience was significantly affected by noticing an elderly gentleman, sitting by himself, openly weeping behind me during the film. We struck up a conversation afterwards and he related to me that he had lost his wife due to cancer some time ago and the film really hit home for him.

The Flow of The Fountain

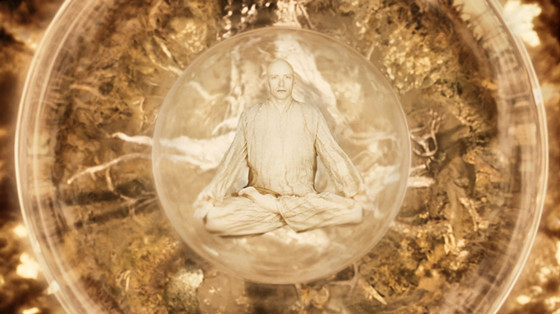

For those of you who have not seen the film (and full spoilers, though nothing in the film is really a surprise), it centers on the character of Tom Creo, a research scientist intent on discovering how to prolong life and cure cancer through simian experimentation, ostensibly to save his wife, Izzi, who is in the latter stages of dying from cancer. What made the film unique was the interweaving of narratives from the past and future, with a story about Tomas, a Spanish conquistador desperately searching for the Fountain of the Youth in the New World to free his captive queen from the Inquisition, and Tommy, a pale, bald, gaunt figure traveling through space in a terrarium-like spaceship with a tree that he speaks to and eats from to survive.

While it’s eventually explained that the conquistador story is his wife’s hand-written (with fountain pen and ink, get it?) allegory of her husband’s heroic attempts to save her, it’s never really clear whether the audience is supposed to read the futuristic story as the actual future or just something in Tom’s imagination. As the film jumps between these three narratives, we begin to see how things in the present (including Izzi’s eventual death) affect both the “past” and “future” stories, thus suggesting a non-linear form of storytelling. This is emphasized when future Tommy has an epiphany and we return to the present and he makes a different choice than he originally made – to spend time with Izzi in the snow when she asks him to join her, rather than angrily refusing as he focuses on his research.

Tommy’s Trip

And while we see Tom stubbornly refusing to accept his wife’s unstoppable demise in the present, we similarly see future Tommy clinging to the hope of saving the tree, a substitute for Izzy, while still being angry with what appears to be the ghost of Izzi accompanying him on his journey. Ultimately, Tommy achieves a kind of enlightenment, accepting that he too will die, and we see him plant a seed on his wife’s grave.

When I saw it, I read that part not as an actual future, but as the process of grieving and the journey towards acceptance that Tom must endure. And even though we don’t see Tom actually dealing with his grief in a realistic way, I assumed that the film was meant to represent his unconscious life and a psychedelic inner journey that transforms him. In fact, in a deleted scene, we see Tommy growing what looks an awful lot like psilocybin mushrooms, and then drinking tea made from them. Along with his lotus position and Tai Chi meditative practices, along with his tattoo ceremonies, it’s clear to the audience that Tommy is on a spiritual journey here.

Biblical or Kabbalistic?

The opening epigraph, written with Izzy’s fountain pen, is a quote from the Book of Genesis:

From the beginning, we are firmly placed in Judeo-Christian mythology – which is strongly contrasted with Mayan mythology (more on that later). Since Adam and Eve have eaten from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in the story, they are banished from eating from the Tree of Life as well, which is protected by a flaming sword.

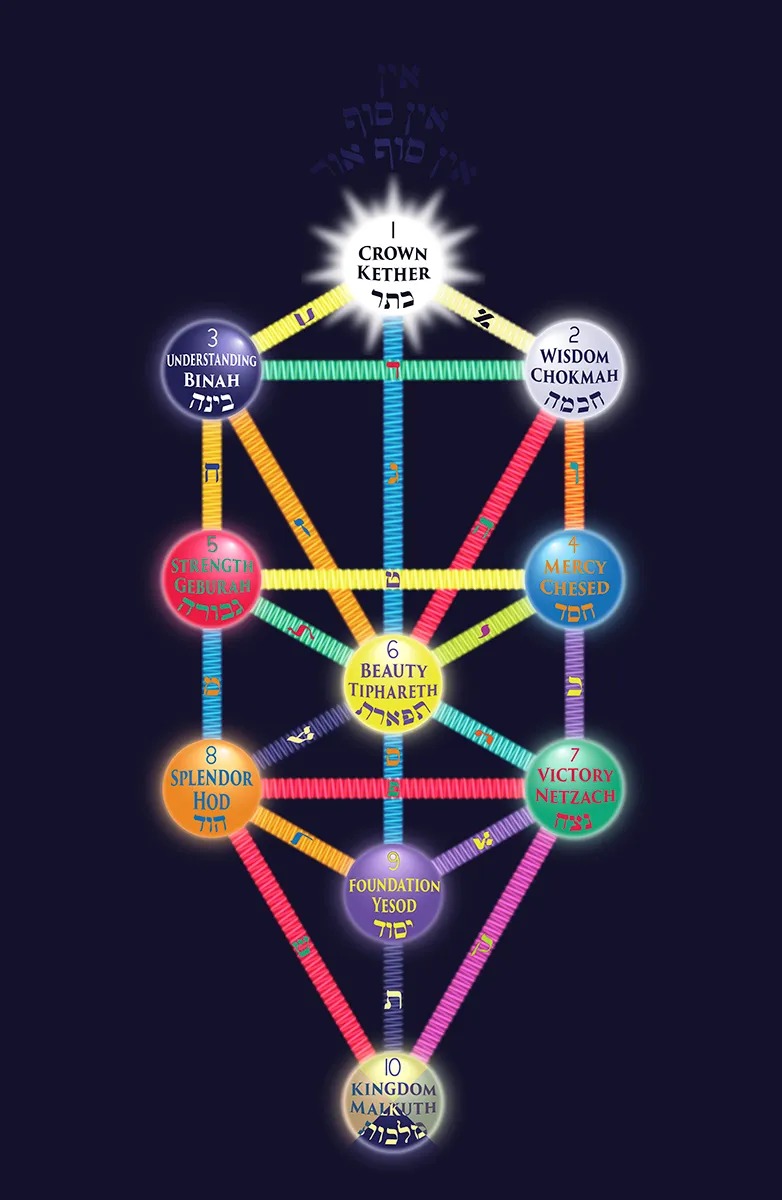

But beyond this biblical surface, there are some clearly esoteric meanings. While Aronofsky’s Pi clearly references Kabbalah with its use of gematria and Jewish mystics, the presence of Kabbalah is a bit more subtle in The Fountain. This opening passage is one of the first clues. Of course, the Tree of Life is a universal symbol, with correspondences in Norse mythology and, of course, Mayan symbology, as displayed in the film. But here, we are very clearly speaking of the Tree of Life from Kabbalah.

In a contemporaneous interview on the film, Aronofsky relates how they had to create their own “fictional tree” for the spaceship scenes, since its inspiration, the “sephiroth tree,” which he describes as two or three hundred feet tall, was impractical to depict. Though it’s not clear what he’s describing here, a sephiroth tree is most likely not a real tree at all, but the symbol used by those who study the Kabbalah, which maps emanations of the divine from the ethereal to the material.

Serpent or Sword

Kabbalists describe two paths for each direction up and down the tree. I’m vastly oversimplifying here, but the journey up the tree from Malkuth (the physical plane) to Kether (the spiritual plane) is the evolution of humankind from the material world through states of consciousness and ultimately depicting the crossing of the abyss and re-uniting with the divine through death and beyond. This journey up the tree is sometimes called the Serpent path, referring to the character that offers knowledge in the Garden of Eden (not originally Satan) and pushes humanity onto its path of transformation.

The path from the opposite direction, down the tree, from the divine to the material world, is called the Lightning Flash, or as it’s sometimes known, the Flaming Sword path. In this case, it is how the divine manifests in our consciousness and in the physical world. It is, as David Bowie describes it in his classic tune “Station to Station,” “one magical movement from Kether to Malkhuth.” Bowie is certainly apropos here as Aronofsky spoke about how Bowie’s “Space Oddity” was an inspiration for the space scenes and Major Tom as the source of the main character’s name. Indeed, “Space Oddity” is another work using space travel as a metaphor for death.

So the “flaming sword” from the Genesis quote at the beginning of the film, could easily be referring to the movement of divine energy into human consciousness. However, towards the climax of the film, when Tommy realizes that he must act to save the tree as his ship approaches the supernova, he actually climbs the tree and leaves the bubble of the ship, thus crossing the abyss into death (and thus, the acceptance of death so important to the film). Tommy, is essentially, traveling the Serpent Path.

Mayan Ruins

From an esoteric standpoint, all of this is fascinating. However, this being 2006, a little more than half a decade from the supposed 2012 Mayan Apocalypse, Aronofsky took an unfortunate detour in his set up for the main character’s journey. In our recent episode of Pop Occulture, Lilith Dorsey and I discussed The Fountain and these more problematic aspects, particularly its use of the Mayan storyline.

So far, I’ve barely mentioned the “past” story that frames the film – where the action of the film starts after that opening epigraph. The first images we see are Jackman as the conquistador fighting his way through Mayan warriors to get to the temple.

Later, we see that this story is Izzi’s creation (and the correspondence between her name and Queen Isabella of Spain is obvious) and she is inspired by her visits to a Mayan collection in a museum, where she studies up on Mayan cosmology, their concept of death and the journey to Xibalba, a kind of Mayan afterlife, through which Tommy believes he can overcome death.

And while Aronofsky studied Mayan cosmology on research trips to Guatemala, and is able to claim that he used actors with Mayan heritage, including an actual Mayan spiritual leader, the perspective here is undoubtedly one of a colonizer.

Colonizing Death

In the Mayan story, the “First Father” sacrifices himself to save creation and Tomas inevitably becomes that figure. We see the moment where the Mayan priest is about to kill Tomas, stabbing him in the stomach and then going for the killing blow, but it is not this moment that is the sacrifice. Rather, in the non-linear narrative, we return to this moment again, later in the film. Once future Tommy achieves a level of enlightenment, we see him appear in Tomas’ place in his lotus position, in pale white light, floating above the kneeling Mayan priest, who recognizes him as the First Father, just before slitting his own throat.

Watching that scene again in 2024 certainly made me cringe due to its unmistakable racial politics. This matched with Izzy’s hobby-like interest in Mayan mythology, and the fact that Tom, as a scientist, is actively using clippings from Central American trees in his work, makes for an unfortunate trope of indigenous cultures literally being subdued to serve a white man’s story.

On one hand, we see Tomas’ folly when he stabs the tree and greedily consumes the white marshmallow-like sap, and flowers burst from his open wound, undoubtedly killing him. On the other hand, future Tommy does more or less the same thing, though a bit less aggressively, when he scrapes the bark, prepares it and eats it in a ceremony.

We are, perhaps, supposed to think that Tom is ultimately missing the point by desperately hanging on to his wife’s spirit, despite his frustration towards her – that all the ceremonies, psychedelic tripping, and spiritual practices amount to just a more focused version of his angry outbursts of violence towards the doctors and nurses who have pronounced his wife dead.

But beyond the Kabbalistic journey, it’s impossible to ignore the elements of the film that are based on colonization tropes. Tom, in his desperate attempts to cheat death, is the ultimate colonizer. If the realm of Death is a place, he wants to colonize Death.

The Thief’s Journey

As a fan and scholar of occultism in cinema, I was fascinated to learn that when The Fountain was originally being planned, the crew watched the occult AND cult classic, The Holy Mountain, among other films, as a guideline for the Mayan jungle scenes. But other than the jungle and mountain settings the two films have in common, Jodorowsky’s journey of the fool towards enlightenment is reflected in Aronofsky’s film, in other, more subtle ways.

It might be tempting to describe The Fountain as a “spiritual film” that nonetheless rejects spirituality, that it is ultimately atheistic. Despite his spiritual practices, Tommy must ultimately submit to the universal truth that every being must die. Yet, as some critics have pointed out, Tommy must go through his journey towards enlightenment to accept that truth.

Similarly, Jodorowsky’s “Thief” must purify himself by rejecting mainstream religion and capitalism, the hedonism of the flesh, and other temptations, and journeying on a mystic path, beginning with alchemical transformation, and a return to shamanistic, indigenous practices. Yet, ultimately, Jodorowsky, as The Alchemist, and leader of the spiritual group attempting to climb the mountain, advises the Thief to leave behind the spiritual pursuit, just as he tells the audience in the final moment of the film that “real life awaits us.”

In The Fountain, Tom comes to realize his spiritual pursuit is for naught and he must ultimately come to terms with his grief, planting a tree on his wife’s grave. But Tom’s journey, and Aronofsky’s film, are not victimless. Even though the film was released almost twenty years ago, much has changed. Even with allegorical tales, it can no longer be acceptable to sacrifice indigenous cultures for that enlightenment.