Just as Denis Villeneuve divided his adaptation of the main Dune novel between two parts, so have I addressed the occulture of Dune in two blog posts. Of course, you could easily write a whole book on this topic. In the last post, I focused on the Bene Gesserit, the supposed “witches” of the Dune-iverse, and particularly their link to actual occult traditions. In this post, I want to focus on some of the psychedelic aspects of Frank Herbert’s work, including the centrality of the “spice” that rules the universe, as well as some of the various attempts to adapt the psychedelic experience that Herbert describes in his work.

Weird Al-Gaib

Villeneuve’s adaptation seemed to mostly downplay the magical, occult, and psychedelic aspects of the book in favor of a grounded approach. We do see occasional uses of the Voice, the Bene Gesserit power that compels all who hear. The Voice is inspired by the ancestral voices of Other Memory that the Reverend Mothers (and Paul, the supposed “Kwisatz Haderach,”) carry. In the two films, we do occasionally hear spooky voices. And Paul has a strange, out of time relationship with Jamis, the Fremen he kills to gain position in the tribe, speaking with the man as if he is fully present in Paul’s reality. Similarly, he has discussions with his future sister, Alia, while she is still in their mother’s womb. So we at least get some sense of Paul’s otherworldly power to communicate through time. Yet, all of this is presented as very matter of fact, without any sense of the supernatural in the style of filming.

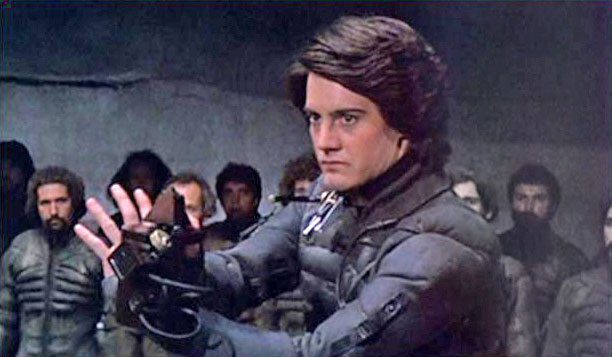

Further, Villeneuve’s adaptation doesn’t present the so-called “weirding way,” the almost magical form of fighting that Jessica knows from her Bene Gesserit training and then teaches to the Fremen. In the SyFy channel adaptation, we see this as an almost superhuman ability to move faster than the eye can see. Of course, in Lynch’s version, he takes this idea and runs with it, creating an element that wasn’t in the books at all: the “weirding modules,” that allow the Fremen to blow things up by shouting “Muad’Dib”! But even the basic weirding way from the books is absent from Villeneuve’s adaptation.

The Spice Must….You Know

Another aspect that’s downplayed, and in some instances left out together, in Villeneuve’s adaptation, is the use of spice. In the novels, the spice is the foundation substance of the universe. While we owe the phrase “the spice must flow,” from Lynch’s adaptations (it’s never actually said in the novels), it captures the importance of melange to the Dune-iverse. Because Arrakis is infused with it, it’s a staple to the Fremen diet, thus the blue tint of the Fremen eyes. We get the sense that there is a connection between the giant sandworms and spice (and that connection is explained in the later Herbert books), and we even see in Dune part 2 how the Fremen priestesses create the “water of life,” the poison that creates Reverend Mothers, when they drown a young sandworm.

Further, the Imperium is mostly addicted to the stuff. Mentats use it to sharpen their senses, the Bene Gesserit use it to gain visions, Emperors use it to prolong their lives. In the prequels, the Imperium starts to use spice as a protection from the plagues created by the machines to wipe out humanity, thus acting as a vaccine of sorts.

But the most important use of spice is that it provides prescience for the Navigators to guide ships as they “fold space.” It’s established in the books, and especially the prequels, without a Navigator, an essentially deformed and forcibly evolved human that swims in a tank of melange gas, spaceships will get irrevocably lost without that ability. Thus, spice is what allows for interstellar travel. It’s notable that the freakish Navigators, featured in both the Lynch film and the SyFy miniseries, are wholly absent from the Villeneuve films.

It’s worth unpacking Herbert’s conceit for a moment. This substance, essentially a psychedelic drug, is what holds the universe together. It has to be harvested from one of the most unhospitable places in the Imperium, and often against the wishes of the people that live there. Without spice, there could be no interstellar travel and whoever controls the spice, controls the universe. Many readers have often noted the parallels between spice and oil, with Arrakis clearly being a stand-in for the Middle East. But spice as an allegory goes beyond even that obvious connection.

Counterculture of Dune

In the Dune-iverse, spice is that Platonic pharmakon, the substance that is both remedy and poison. It is the method through which human consciousness is expanded and humanity evolves. But it is also the thing that major powers go to war in order to control, that creates desire and requires its fulfillment, that ferments both addictions and rebellions. Thus, it also has the third meaning of the Greek term. It is also a scapegoat – that vehicle through which the Imperium pours their sins and shortcomings. It is the both the object and tool of capitalism. Like the mysterious “dollar” in American capitalism, the stability of the Imperium is wholly based on the constant flow of supply and demand, where the spice must be relied upon, or else everything falls apart.

From a psychedelic standpoint, we can approach Herbert’s spicy creation as a key that can unlock many doors and push humanity to a higher plane of consciousness. Yet, with all the religious, political, and economic baggage surrounding spice, it seems that Herbert’s takes on psychedelia come with many warnings. As many Dune readers have noted, Herbert looked at what was happening in the early days of 60s counterculture, and both celebrated it and cautioned against it, warning us that there would be no easy path, no convenient Messiah (or drug, for that matter) to break us free from the oppression of religion, economics, or even basic human selfishness.

The Jodorowsky Factor

When Dune was first being developed as a possible sci-fi blockbuster, it is important to remember, it was in the early 70s, when the thrill of the counterculture was, if not gone entirely, fairly diminished. Looking at the history of Dune, one cannot leave out the crucial chapter which was the failed, entirely out of this world adaptation by eccentric auteur Alejandro Jodorowsky, chronicled in the acclaimed 2013 documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune. Jodorowsky, having just released the occult (and cult) classic The Holy Mountain, wanted to turn his eye towards Herbert’s novel. Though as the documentary indicates, it’s not clear Jodorowsky ever actually read the novel, having only a vague notion of the actual storyline.

That was no obstacle for Jodorowsky, who notoriously relied on his own personal gnosis and vision to create his movies, such that many deemed it would be impossible for him to realize that vision in a reasonable early 1970s Hollywood budget and technology. If you haven’t seen that documentary, I highly recommend it. Jodorowsky’s Dune would have made cinematic history, and would have likely have changed the trajectory of filmmaking for the future. Salvador Dali as the Emperor, Mick Jagger as Feyd-Rautha, Orson Welles as Baron Harkonnen, David Carradine (Kung Fu) as Leto. Soundtrack by Pink Floyd. Can you imagine?

It’s also notable that Jodorowsky’s production was the first to utilize the designs of occult artist H.R. Giger, and the special effects and design team went on to carry that signature style into movies like Alien. In fact, the documentary points to all the ways Jodorowsky’s ideas and specific designs found their way into a panoply of 80s films and beyond.

Captain Planet

In The Holy Mountain, we see Jodorowsky’s vision of the journey of the Fool, perfecting himself through both alchemical and shamanic means, only to ultimately be guided back to mundane life, while the final stage of initiation for the ensemble at the end of the film transitions into a meta acknowledgment that we are indeed watching a movie. Jodorowsky both celebrates that initiatory path, while at the same time, exposing it as play and performance.

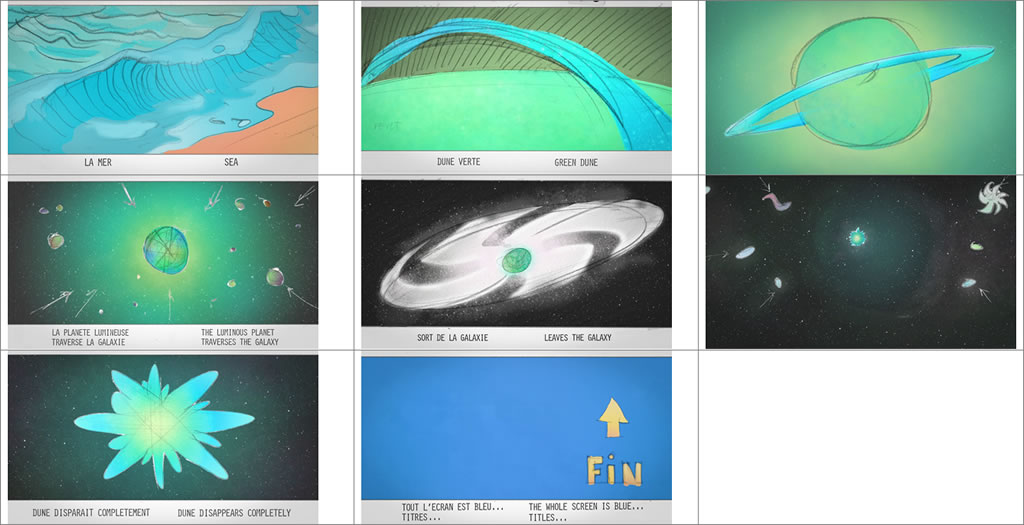

With his Dune adaptation, Jodorowsky takes that path a bit more seriously, but dramatically changes the ending of Herbert’s novel, having Paul actually be killed in the battle with Feyd-Rautha, but having his spirit infuse all of humanity. The final sequence that the director envisioned is described in detail in the documentary, in which humanity evolves instantly, and the desert planet of Arrakis is transformed into a lush green planet. Further, the planet itself becomes a wandering star, bringing enlightenment to the universe.

New Age?

Jodorowsky’s much more optimistic view of Herbert’s universe, albeit with gruesome torture scenes, seems to echo many occult narratives of a new age, the Age of Aquarius, or Aleister Crowley’s New Aeon. Though it’s not clear how aware Herbert himself was of Jodorowsky’s plan to “rape” his novel, the later Dune novels did indeed transform Arrakis from a desert planet to a green oasis, a full eight years after Jodorowsky’s aborted effort (and thousands of years later in the storyline).

But Herbert’s “Golden Age” of the God Emperor, the sandworm/human hybrid son of Paul Atreides, who rules for over a millennia, is not necessarily the new age that occultists imagined. While there is peace and stability in the Imperium, it is also a time of untold oppression, as depicted in the 1981 novel God Emperor of Dune. So once again, Herbert’s connection to occult themes and ideas is deeply ambivalent.

Esoteric Lighting Design

Later adaptations of the novel would incorporate esoteric and occult symbolism. The SyFy Channel adaptation in 2000 is a strange case. Given the budget constraints of a pre-streaming, made for television miniseries, the production relied on primarily theatrical tricks and effects. Prefiguring the digital environment of the AR wall used in the current Star Wars and Star Trek television shows, the SyFy production used fully painted scrim backgrounds and theatrical lighting to create their environments.

Legendary cinematographer and lighting designer Vittorio Storaro, from classics such as Apocalypse Now and The Last Emperor, had his own highly developed theory of color as it pertained to capturing emotional states in a film scene, and he readily applied that theory to the Dune miniseries. Storaro explains his very consciously esoteric approach to color and lighting in several special features on the miniseries DVD. Working off the classic four elements of earth, air, fire, and water, Storaro used colors associated with water for Arrakis, earth for House Atreides, fire for House Harkonnen, and air for House Corrino. Thus, his Arrakis lighting often had greens and blues in their landscapes.

Occult Ambivalence

Further, moments of prescience, connections to ancient voices, and scenes of the supernatural were represented with classic laser effects on a green screen, one of the many ways that the miniseries doesn’t hold up to today’s effects standards. I point this out, however, to demonstrate the ways that earlier adaptations leaned into the psychic and supernatural elements of the novels, even enhancing them. However, Villeneuve’s adaptations mostly eschews these elements, preferring to merely hint at supernatural elements in a subtle, subjective way, through Paul’s (and very occasionally, Jessica’s) point of view.

Of course, Villeneuve’s vision won’t be complete until we see the Dune Messiah adaptation that he is planning, to round out the trilogy at some point in the future. Not only will this third film address the “Chani problem,” but will ultimately have to demonstrate Herbert’s conception of Paul as a failed messiah and how his character responds to that. As Villeneuve and others have often noted, Herbert’s novels were cautionary tales about putting one’s faith in institutions and religious beliefs, predicting so much of what we continue to deal with in the early 21st century. These adaptations also present the tensions and ambivalence around occult ideas that pervades our current popular culture.