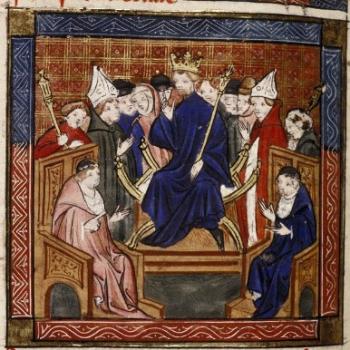

In the previous article, the 8th c. forgery known as the Donation of Constantine was discussed. More specifically, a claim made by a Protestant debater that the papacy was established (seemingly ex nihilo) on the basis of that document. There the Donation was placed in its proper historical context, and a distinction was made between temporal and spiritual authority. It was argued that the Donation is better seen through the lens of this distinction, on which the Popes from St. Gelasius (d. A.D. 496) on have made. Furthermore, it was argued that the Donation of Constantine contains nothing with respect to papal primacy that was not being proclaimed by the Popes themselves centuries earlier, at least from the time of St. Damasus (d. 384).

Between the latter two Popes reigned one of the most well-known of all, St. Leo I (r. A.D. 440 – 461). The present article takes the “nothing new” argument from the previous one, and focuses on Leo who was known to have a robust sense of the prerogatives attached to the bishopric of Rome, by virtue of its connection to St. Peter the Apostle. With this in mind, the present article raises the question: if, as the Protestant interlocutor claimed, papal authority was established by the 8th c. Donation, how does one explain the view(s) taken by Pope St. Leo I in the 5th c.?

Spotlight on Pope St. Leo I

In one of his works on the primacy of the Bishop of Rome, Dr. James Likoudis quotes an early twentieth-century Russian Orthodox church historian (V.V. Bolotov) on St. Leo I’s view of his own office. Keeping in mind the question just posed, here is what is written:

“This primatus, this principatus, of the apostle Peter is not a temporary but permanent institution. He governs the Church visibly through his successor. The relation borne by Roman bishops to St. Peter, the chief of the Apostles, is a close reproduction, in its depths and in all it involves, of the consortium potentiae of St. Peter with Christ…In the same way the whole construction of the Church reproduces, according to Leo the Great, the diversity of the relations that existed between the Apostles. Though all were chosen equally, there was not equality of authority amongst them; so in the same way the Bishops, equal amongst themselves in sacerdotal dignity, are not so in canonical rights, nor are they equal in their participation in the Government of the Church. This administration over all the Churches is incumbent upon the Bishop of Rome, principaliter, ex jure divine [principally, by divine right]…The episcopatus universalis [universal bishopric] of the sovereign pontiff of Rome, as taught by St. Leo the Great, does not exclude the equality of the hierarchy, that is to say, the sacramental equality of all bishops but only the plenitude potestatis [the fullness of power]…It could never become necessary to condemn a Bishop of Rome; he might have his shortcomings but they are compensated for and rectified by the merits of Peter. A Roman Pontiff can never really fail in any serious degree”.[1]

However unwelcome V.V. Bolotov’s analysis of Pope Leo’s understanding of the papacy may be to his modern Eastern Orthodox co-religionists (if online amateur apologists be a useful standard), it is not an uncommon historical opinion, even among non-Catholic Christians.[2] Even the Encyclopedia Brittanica’s entry on Pope Leo I affirms that he was “a master exponent of papal supremacy”, and that he “was devoted to safeguarding orthodoxy and to securing the unity of the Western church under papal supremacy”. That being the case, why exactly is the Donation of Constantine relevant to a discussion on the origins of the papacy? Can we really not all at least find common ground in the claim that Pope St. Leo I was “a master exponent of papal supremacy”?[3]

[1] In James Likoudis, The Divine Primacy of the Bishop of Rome and Modern Eastern Orthodoxy (New Hope: St. Martin de Porres Lay Dominican Community, 2002), pp. 69-70. Brackets in Likoudis.

[2] Cf. Bruce L. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1995), pp. 132-135, 137-139.

[3] For an analysis of Leo’s understanding of the papacy through the lens of his own writings see Robert Eno, The Rise of the Papacy (Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1990), pp. 102-117). The author is Catholic, but Leo’s works are cited from by number.