On September 4, 1957, Black students who would later be called the Little Rock Nine made their first attempt to enter Little Rock’s Central High School under a desegregation order. When the students were not allowed to enter, President Dwight David Eisenhower issued executive orders for the students to be enrolled, but the orders were ignored by Arkansas authorities. On September 24, President Eisenhower ordered the National Guard to enforce desegregation of the school and admission of the students. An infamous photograph of a jeering crowd memorialized the bitter weeks.

On September 2, 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace ordered state troopers to surround Tuskegee High School to prevent its court-ordered desegregation, as thirteen Black students attempted to enter on the first day of classes. Within weeks, the school permanently closed after all of the white students – roughly, 275 – withdrew from the school.

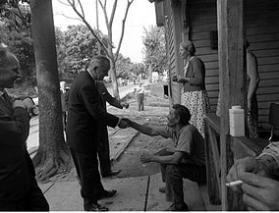

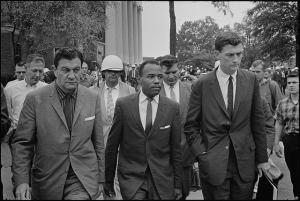

On September 30, 1962, a group of marshals, including the deputy attorney general, escorted James Meredith to his dormitory at University of Mississippi – 1½ years after Meredith had begun his quest to continue his college education there. After nine years of service in the U.S. Air Force, Meredith had studied at Jackson State College, and applied to Ole Miss as a transfer student. His application was originally rejected, but after court rulings and intervention by federal marshals, he was finally escorted to his dorm. For three days, marshals, Mississippi National Guardsmen and U.S. Army soldiers faced off with a mob of civilians armed with guns, Molotov cocktails, and other weapons. By October 2, when Meredith officially became the first black student at Ole Miss, one hundred sixty marshals and forty-eight soldiers were injured. Two civilians were killed, and nearly three hundred citizens were arrested. The military reportedly continued to occupy Oxford for almost ten months.

On September 15, 1963, four young Black girls – Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins and Cynthia Wesley – died in the bombing of Birmingham’s 16th St. Baptist Church – a bombing carried out by segregationist members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Just these four dates in our nation’s not-so-distant past remind us that September has been a month during which our nation has suffered greatly as the struggle for justice and freedom for all persons waged on.

Too much of that history has been forgotten – or worse, suppressed. Voices still call for the suppression of that history.

But Rev. Dr. William Barber, II, of Repairers of the Breach and the Poor Peoples Campaign, wants September to be known for something else: our nation engaging in days of fasting and prayer, telling our shared history that too many have forgotten or never knew, and reframing our nation’s story from that of hatred to that of love.

Rev. Dr. Barber wants to “take back the mic” from those who churn out any messages other than messages of unity.

Rev. Dr. Barber has presented us with a tall order. With FBI statistics showing a surge in hate crimes, and recent killings in Jacksonville, Florida by a man leaving a racist manifesto, we are made increasingly aware that hatred has not ended. The commandment to love God and neighbor is too frequently forgotten – along with the consequences for our human disobedience.

Voices advocating justice may never have really had the mic in the first place.

What happens if September becomes a month during which we commit to honest conversation about our history? What happens if September becomes a month during which we reframe the narrative?

Scriptures tell us what happens when we forget our history.

When God entered into covenant with Abraham and promised him more descendants than could be numbered, Abraham likely didn’t imagine that the covenant would be fulfilled on the foreign soil of Egypt – and that his descendants would be enslaved there.

Yet our scriptures tell us exactly that. Abraham’s descendants were few when they arrived in Egypt to escape famine in their home. They had been welcomed by Abraham’s great-grandson, Joseph, who after having been sold himself into slavery by his own brothers had become instrumental to Egypt’s king by advising Pharaoh how to amass enough resources to sustain Egypt’s people as well as others through the famine.

But the day came when no one – neither pharaoh nor the people – remembered Joseph. No longer remembering Joseph meant no longer remembering the contributions he had made to the Egyptian economy and welfare. No longer remembering Joseph meant no longer remembering that Joseph’s God had providentially delivered Egypt from the famine. No longer remembering Joseph meant no longer remembering how long Joseph’s people had lived peaceably among the Egyptians and contributed to their world.

When Pharaoh and the Egyptian people no longer remembered their shared history with the Israelites, it was easy for fear to set in: The new king feared that the now-numerous and strong Israelites could overthrow the Egyptian empire. That fear gave rise to the Egyptians choosing to enslave the Israelites, and to subject them to harsh labor.

But the Egyptians discovered that the more the people were oppressed, the more numerous they grew.

If oppression and hard labor would not slow the growth of the people called Israel, Pharaoh had another trick up his sleeves: He summoned Israelite midwives, telling them to kill the male Israelite babies at birth.

But two midwives, Shiphrah and Puah, remembered something important about the history of their people and the nature of their God. They understood that when we are asked to take actions that are in violation of God’s laws and subject other human beings to injustice, we should view such actions with great skepticism.

Because the midwives feared disobedience of God over disobedience of Pharaoh, one of the infants they allowed to survive would grow up to become a privileged member of Pharaoh’s household. That infant would grow to become a leader – even if at first a hesitant one – to help free the Israelites from slavery.

That infant survived because midwives were disobedient. That infant survived because his mother, too, was disobedient; she refused to give up on her son, trusting his fate to the God of Israel who had preserved a people even through slavery. That infant survived because even Pharaoh’s daughter was disobedient: When she found this Israelite baby, she chose to raise him as her own son, with his own mother becoming his nursemaid and, no doubt, helping to shape his life, his understanding of his people and his understanding of Israel’s God even before he took on an identity as a member of Pharaoh’s household.

That infant was Moses – Moses, who would be called by God to lead his people from their bondage to freedom. Moses delivered God’s stern message to Pharaoh, who, unpersuaded, brought grief, suffering and a watery death upon his Egyptian people in his own disobedience.

What could have happened if Egypt had only remembered its past?

What could happen if September becomes a month in which we commit to remembering our past and engaging in honest conversation about our history?

For, indeed, our shared history gives us cause for celebration and lamentation; it gives us cause for remembrance and repentance. Our shared history also gives us cause for hope: Taking time to learning our shared history from the perspective of neighbors – and sharing the mic with the disenfranchised – may save us all from drowning in a sea of death and despair.