Summer for many academics means visiting archives or writing, and I’m certainly not an exception to that rule. As I’ve been working through the (many) archival photos I took last summer and writing on a book project on emotions in medieval York, I’ve spent a lot of my summer thinking about the ways that the teachings and preaching we listen to shapes our assumptions, actions, and emotions. A March study highlighted the fact that fewer Americans attend church at all than two decades ago, with around 30% of American Christians saying they attend church every (or almost every) week. And even those who do attend every week still spend far less time in church than they do out of it, and sermons often take up no more than an hour of our week. How much does it matter what those say?

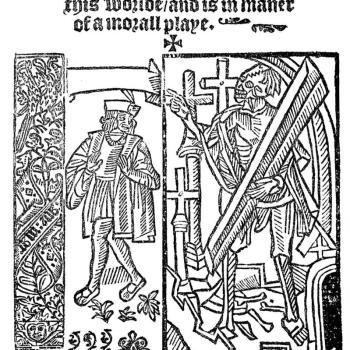

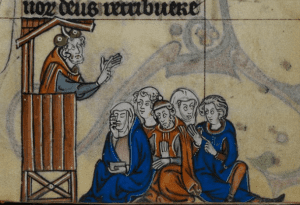

Medieval Preaching…

In my first book, Women, Dance, and Parish Religion in England, 1300-1640, I argue that what we listen to in sermons matters quite a lot. How clerics talked about both dance and women eventually shaped how people thought about both of those things. Sermon authors started by talking about both dance and women as sometimes holy and sometimes problematic: as separate topics that needed to be addressed in their contexts. As sermon authors became less diligent in maintaining clear distinctions between discussions of dance and of women, and as sermon authors became increasingly willing to make exaggerated statements about the problems with both to make their points, the ways that the people of the parish treated women shifted for the worse. Ann Thayer’s work on sermons in the Reformation shows how “the ideas taught in regular preaching provided the religious and mental equipment with which people made sense of their lives and evaluated, and sometimes adopted, new understandings,” with different emphases in medieval sermon cycles leading to different responses to Reformation theology in sixteenth-century parishes (Thayer, “Ramifications of Late Medieval Preaching: Varied Receptivity to the Protestant Reformation,” p. 361, in Preachers and People in the Reformations and Early Modern Period).

In working on this second book, I keep noticing just how true it is that what we hear eventually shapes everything about what we do. A big focus of much of my summer writing has been a chapter on the emotion of love in medieval York– what did religious texts (sermons, catechisms, mass books, and plays) say love was? How could you recognize love when you felt it or saw it? And how did that definition of love shape their actions?

Without giving away the entire chapter, the results of this summer’s reading have been interesting. First, while the types of texts talking about love in medieval York were all written for different purposes (a catechism is quite different from a mass book, and a mass book is quite different from a play!), when they talk about love, they keep coming back to the exact same points: love means worshipping God and caring for neighbor. It has an emotional component, but that emotional component should always be directed outwards, towards God (first and foremost) and towards neighbor (defined very broadly). Many of these texts emphasize Luke 10:27 as the reason for this framework for love: the summation of the whole law into loving God and loving neighbor.

This framework shows up in the ways that the people of medieval York interacted with each other. A key rubric for deciding who was in the right and who was in the wrong in marriage disputes was whether the marriage increased the community’s love of God and neighbor or decreased it. Marriages that seemed to result in better church attendance, more charitable giving, or other signs of loving God and loving neighbor received the support of the diocesan courts. Marriages that had clearer signs of emotional attachment (like children, or passionate exchanges of words, or the like) but less clear signs of “godly love” often received less support. The way that love was defined and taught in these sermons and catechisms had enough of an impact to shape how court cases turned out– clearly what the people of York listened to mattered, especially if you were involved in one of these contested marriage disputes! And while some of the ways these medieval people talked and thought about love might seem odd to us, the emphasis on loving God and loving neighbor in tangible, observable ways is one that is hard to critique.

… And Modern Podcasts

But what about for us today? The impact may not always be as obvious, but I think, in the age of podcasts and streaming and social media, we certainly need this reminder that what we listen to shapes how we think and act. As of 2023, according to a Pew research study, 42% of Americans 12 ages twelve and older listen to at least one podcast a month. And of the 451 top-ranked podcasts in the US, 2% of those are about religion. And this doesn’t even take into account online sermons, which sometimes propel extremely problematic figures like Mark Driscoll to national platforms, as detailed by the “Rise and Fall of Mars Hill” podcast. Another Pew research study says that 20% of all US adults watch religion-focused online videos and 15% listen to religion-focused podcasts- almost as many Americans as attend church on a weekly basis. We can *listen* to more sermons and teaching materials than ever before– but without any of the accountability of seeing how the people who preach or develop these materials live their lives, apply their own teachings, or treat those around them. Unlike the people of medieval York, we have no idea if the pastors and teachers we listen to are loving God and loving their neighbors.

And that, I think, should be the warning we take from thinking about the power of preaching (and teaching) both in medieval York and today. The theology in a sermon is never in a vacuum; no matter who is doing the teaching, there are a host of cultural assumptions that tend to sneak in, like the assumption in medieval York that love doesn’t really have much to do with marriage. We can spot these assumptions from a chronological or geographic distance, like I’ve been doing this summer as I’m working on my book. But they’re much harder to spot in the podcasts, videos, and reels we consume for hours each week if our listening habits are anything like the national statistics. Figures who live in ways that contradict their messages could have their assumptions shape the ways we treat our friends and spouses and neighbors– and we might not even notice, at least until the damage is done. When we remind ourselves that what we listen to matters, we will hopefully be more discerning in what we choose to hear. I personally think that if American Christians monitored the lifestyles, actions, and words of their podcast preachers as closely as they do Taylor Swift and her lyrics, we’d be much more likely to rightly love God and neighbor.