William F. Vallicella has an interesting post on his blog Philosophy in Progress on “mortalism,” the doctrine that when the body dies the “soul” or mind dies as well. As I’ve written elsewhere, sometimes Mortalism goes by the name of animalism, that we are simply animals and therefore when our bodies die so does whatever it is within us that makes us “us.”

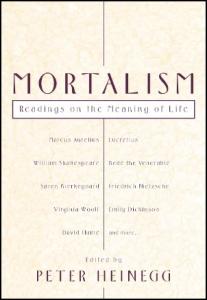

Vallicella refers to the work of the former Jesuit turned atheist apologist Peter Heinegg, who died in 2021, who edited an anthology of articles on the Mortalist position and embraced it himself.

Vallicella refers to the work of the former Jesuit turned atheist apologist Peter Heinegg, who died in 2021, who edited an anthology of articles on the Mortalist position and embraced it himself.

What is interesting is how Vallicella analyzes Heinegg’s argument – or rather, lack of argument.

This is what analytic philosophy does very well. It shows how conclusions often don’t follow logically or necessarily from stated premises.

And this is precisely the case with Heinegg’s argument for Mortalism.

Here is how Heinegg himself made his argument:

“As surely as the body knows pain or delight, the onset of orgasm or vomiting, it knows that it (we) will die and disappear. We have a foretaste of this every time we fall asleep or suffer any diminution of consciousness from drugs, fatigue, sickness, accidents, aging, and so forth. The extrapolation from the fading of awareness to its total extinction is (ha) dead certain (Mortalism: Readings on the Meaning of Life, Prometheus, 2003, p. 13, cited by Vallicella).”

And here is how Vallicella analyzes logically Heinegg’s argument:

“Premise: We experience the increase and diminution of our embodied consciousness in a variety of ways.

Therefore…

Conclusion: Consciousness cannot exist disembodied.”

Vallicella points out that, while the premise is undoubtedly true – we do experience the diminution of our consciousness through sleep or alcohol – the conclusion simply doesn’t follow from the premise.

The fact that we experience sleep or drunkenness seems to suggest that our bodily states do have an impact on our conscious awareness. Clearly our body impacts our consciousness. But that in no way proves that our body and our consciousness are identical.

That is the problem with so many philosophical arguments: they often draw conclusions far beyond what the evidence itself suggests or the premises allow.

Vallicella points out that it could very well be possible that, once our body and soul are separated, then the body’s impact on consciousness might disappear.

“It might be like this: as long as the soul is attached to the body, its experiences are deeply affected by bodily states, but after death the soul continues to exist and have some experiences, albeit experiences of a different sort than it had while embodied,” Vallicella explains. “On such a scenario, the variations in the quality of consciousness that Heinegg adduces would be exactly what one would expect given the soul’s embodiment.”

This is precisely what Near-Death Experiences (NDEs) suggest, he says, although he is carefully not to make the same mistake as Heinegg and claim that NDEs prove the existence of post-mortem consciousness.

In fact, a Mortalist like Heinegg might dismiss NDEs by pointing out that “near-death” means precisely that – “near” death and not actual death – and that therefore you can’t draw conclusions about what happens after death from experiences you have while still alive, no matter how suggestive they may be.

But Vallicella, says, that same rigor should also be applied to experiences of sleep and drunkenness.

“By the same token, however, a consistent mortalist should realize that this same principle — that no conclusions about what happens after death can be drawn from experiences one has while still alive — applies to his experiences of the waxing and waning of his consciousness,” Vallicella concludes. “He cannot validly infer from these experiences that consciousness cannot exist disembodied.”

Anyway, I encourage everyone to read the original post.

Vallicella reacts strongly to the smug certainty that Heinegg evinced – and points out that, as is so often the case with atheist arguments, there can be as much blind faith in them as in many theistic claims.

Robert J. Hutchinson is an award-winning Catholic writer and the author of numerous books of popular history, including Searching for Jesus: New Discoveries in the Quest for Jesus of Nazareth (Thomas Nelson), The Dawn of Christianity (Thomas Nelson), The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Bible (Regnery) and When in Rome: A Journal of Life in Vatican City (Doubleday). Born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, he attended Catholic schools, studied philosophy at a Jesuit university, moved to Israel to learn Hebrew, and then earned a degree in New Testament studies. Hutchinson is currently pursuing graduate studies in the Philosophy of Religion in Europe and writes for many publications. You can read more about the author at www.RobertHutchinson.com.