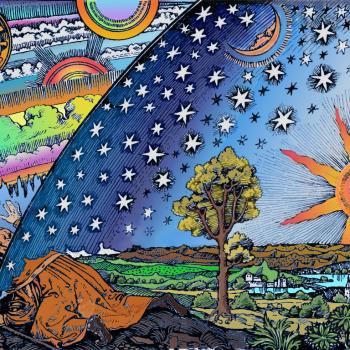

What actually is the afterlife? In Adolf von Harnack’s magisterial summary of early Christianity, translated into English as What is Christianity, he claims that the distinctive teaching that sets Christianity apart from all other world religions is its strange belief in physical life after death. From the earliest records we have of the Jesus movement, what struck ancient people the most about the followers of the executed Jewish messiah was their fearlessness in the face of death.

Roman writers noted that Christians faced execution with unusual courage, even indifference, often choosing martyrdom rather than accepting the merely formal renunciation of their religion demanded by Roman civic officials. Even the Stoic philosopher Epictetus described this fearlessness among the “Galileans” as a kind of madness, and the Roman physician Galen insisted that the idea that Christians “are free from the fear of death is a fact which we all have observed.”

However, what’s unusual about this Christian belief in the afterlife is not merely its affirmation of a postmortem existence. Other religions have taught and continue to teach that human beings will survive death in some sense – for example, as part of a collective cosmic consciousness, or through reincarnation or perhaps as disembodied spirits.

Is the Afterlife Physical?

Yet Christianity and at least some sects of Second Temple Judaism taught something quite different: that people will survive death physically, that the afterlife will be a continuation of the same bodily existence lived before death (although also different).

Hints of this odd belief exist in some of the earliest texts of the Hebrew Bible, such as Job (“I know that my Redeemer lives, and on the last day I shall rise out of the earth, and I shall be clothed again with my skin,” 19:25-26). The earliest Christians, however, added something radically new to this odd Jewish belief in physical immortality: they insisted that they had already seen it happen… and were witnesses to its reality. The long-promised hope in life after death was happening, not in some distant future, but right now.

No matter how much Christian intellectuals have tried over the centuries to rationalize away belief in physical resurrection, the earliest evidence of the Jesus movement is unmistakable: Christianity is based upon the claim that Jesus of Nazareth, executed by the Romans as a potential trouble-maker, was restored to life in a transformed existence.

No less an authority than the Apostle Paul, who would spread the new faith throughout the Roman world, insisted resurrection was the very foundation upon which everything he taught hinged. “Now if Christ is proclaimed as raised from the dead, how can some of you say that there is no resurrection of the dead?” he wrote to the community he founded in the Greek city of Corinth. “But if there is no resurrection of the dead, then not even Christ has been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain.” In fact, Paul continued, if resurrection doesn’t happen then believers in Jesus “are of all people most to be pitied (1 Cor 15: 12-14, 19).”

How Would Bodily Resurrection Be Possible?

Christian philosophers and theologians have thus wrestled with the metaphysical, even practical implications of this strange belief in a bodily afterlife for more than eighteen hundred years, beginning as early as Justin Martyr in the second century. Thomas Aquinas thought long and hard about how a bodily afterlife could be possible, and struggled with the philosophical problems of identity involved – not least because the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 affirmed, as a de fide article of faith, that all “will rise with their own proper bodies which they now bear, so that they may receive according to their deeds, whether good or evil (CCC 999).”

In recent years, Christians working in the field of analytic philosophy have also returned with new vigor to face the problems associated with belief in bodily resurrection. Their conclusions often shock but also intrigue ordinary believers in the pews.

The problem with belief in an immaterial spirit or soul is that it means the person’s body truly dies. This may seem obvious, but what is not obvious is that it’s difficult to argue for a resurrected body that is still the body of the person who died. In other words, an all-powerful God could very well create an exact replica of the body of a person who died, but it would be, or so philosophers insist, a replica, not the person’s actual body.

It would not be the same body that lives again but someone, or something, else.

Could Humans Survive Death by Never Really Dying?

Thus, this account is not very different from belief in reincarnation, that souls can take on new bodies the way someone takes on new clothes, whereas some theistic religions, such as Christianity, Judaism and Islam, have always insisted, to the contrary, that God would raise up the same body, not create a new body.

Next time, we will look at an alternative theory… which is materialism. This is an attempt to imagine if God could somehow save human beings from death by basically making them survive death physically. The most famous advocate for this position is the contemporary Christian philosopher Peter van Inwagen, but other philosophers in this camp include Kevin Corcoran and Hud Hudson (with help from the substance dualist Dean Zimmerman).

Robert J. Hutchinson is an award-winning Catholic writer and the author of numerous books of popular history, including Searching for Jesus: New Discoveries in the Quest for Jesus of Nazareth (Thomas Nelson), The Dawn of Christianity (Thomas Nelson), The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Bible (Regnery) and When in Rome: A Journal of Life in Vatican City (Doubleday). Born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, he attended Catholic schools, studied philosophy at a Jesuit university, moved to Israel to learn Hebrew, and then earned a degree in New Testament studies. Hutchinson is currently pursuing graduate studies in the Philosophy of Religion in Europe and writes for many publications. You can read more about the author at www.RobertHutchinson.com.