As I perused Abigail Shrier’s new book, Bad Therapy—which argues that American kids are over-diagnosed with mental health ailments, overtherapized, and underdisciplined (and is a must-read for everyone, especially parents)—I learned that among the reasons why Gen Xers first became enamored with psychotherapy was their admiration for the award-winning 1997 film, Good Will Hunting.

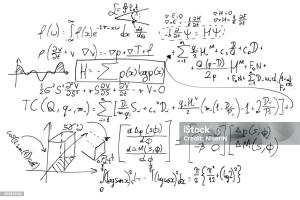

This movie, for which I share great admiration, stars Matt Damon as 20-year-old Will Hunting, a mathematical genius from South Boston who was orphaned and abused as a child, leaving him as emotionally stunted as he is intellectually gifted. To avoid time in prison for initiating an unprovoked assault on a guy who used to bully him in kindergarten and punching a police officer who was trying to break up the ensuing melee, Will is mandated to attend psychotherapy.

His analytical brilliance notwithstanding, Will approaches his succession of therapists from the vantage point of a child. Not yet 21 and not in control of his own fate, he is in therapy by virtue of coercion, not of his own accord. So, it is not unreasonable to view the film’s story of its title character’s experiences with mental healthcare through a juvenile lens.

Which is why anyone who would come away from Good Will Hunting with a romanticized view of psychotherapy for kids must have been watching a different film.

Enraged to be attending therapy against his will but aware that prison would be worse, Will is a less than compliant patient for the first two celebrity therapists he sees. He belittles and condescends to, first, a traditional behaviorist and, second, a new-age hypnotist much like a twelve-year-old with an attitude does when testing a parent. Proving to be exactly the weak, self-serving charlatans that Will assumes they are, each of these therapists rejects Will as a new patient.

These are super-stars in their fields, used to deference and gratitude; they don’t want to work this hard. And they would not know how to help Will—who actually needs emotional and spiritual direction to overcome a severe attachment disorder related to early abandonment and abuse—even if they did. So, they abandon him.

Just like they would abandon our children if we had not raised them to be so amenable to their nonsense. That is, so easy to unnecessarily “treat.”

The next therapist Will sees, Sean Maguire, is no celebrity. He is a grieving widower who grew up in the same working-class, predominantly Irish Boston neighborhood from which Will hails. Although he went to Harvard, Sean eschewed the glitz and glitter that attracted many of his peers, choosing a grounded life rich in rootedness—teaching at a community college and counseling veterans—instead.

In his first meeting with Sean, Will tests his new therapist’s boundaries, just as he did with the others. Only this time, the adult in the room acts like one. He meets Will’s attempts at denigration and belittlement with calm engagement and firm boundaries, established in part through the intimation of superior physical strength.

The next week, Sean shows up. Ignoring Will’s renewed attempts at belittlement, he gives a monologue that establishes for Will intellectually what he first established primally: I am a man, and you are a boy; I have authority, and you do not. Sean tells Will that he is “nothing but a kid” who does not have “the faintest idea what you’re talking about.” He recounts his own rich life experiences and sets them against Will’s mostly empty existence in order to demonstrate that the wisdom that comes from connection with others is far more valuable than the information that comes from the books Will memorizes at a glance. Love, Sean makes clear, is more valuable than genius. Sean ends his monologue by offering the possibility of love to Will, telling the fatherless boy that nothing he’s done has disqualified him as a patient: “I’m fascinated. I’m in.”

Obviously, Sean’s relationship with Will violates every tenet of psychotherapy.

He firmly and finally establishes himself as the superior authority on everything—up to and including the patient’s life—before asserting his unwavering commitment to be there for the patient with an affective intensity that is personal rather than professional.

This is fatherhood, not therapy. Viewers must have trouble identifying it as such because we’ve decided that the establishment of authority has no more place in parenting than it does in therapy. Which is likely part of why we’re having such trouble turning children into adults—and particularly boys into men.

For young males in particular, the mutually understood physical superiority of the father is an inextricable component of establishing his authority, without which there can be no respect.

By the time the climactic scene of the movie arrives—when Will finally accepts Sean’s repeated assurance that the abandonment and abuse he suffered are “not your fault” and hangs onto Sean weeping in repentance while Sean weeps for the joy of Will’s being able to weep—Sean has completed 20 years of fathering in one.

Viewers who endorse today’s iteration of childhood psychotherapy and the gentle parenting that increasingly resembles it want to behave toward their own kids like Sean does toward Will in this redemptive scene. Only without earning it.

It is Sean’s insistence that Will toe the line through coercion that enables him to eventually tow it through respect. Parenthood does not work any other way. Which is exactly why so much of our parenting is not working. And instead of going back to these basics, we abandon the idea that there should be any lines for our kids to toe.

Instead of turning therapy into parenthood, as Sean does in Good Will Hunting, we’re turning parenthood into therapy.

Since unneeded therapy (i.e., the vast majority of it) is proven to make kids both less happy and less successful, we should really stop doing that.

After all, if our kids had parents who acted like parents rather than like therapists, most of them would find today’s iteration of childhood therapy, with its patronization and its coddling, insulting unto rejecting it anyway.

And good riddance.