Thanks for joining me for this series of posts on Mises University 2017. If you missed my first post where explain what this is all about, it’s here. I hope you learn something from this – something about economics, history, and political-economy – something about an uncommon, but very old perspective, a way of thinking about human action and social order with which you may disagree, but also may not fully understand. I am admittedly a sympathetic reviewer, but I nonetheless hope to give an even-handed account of these lectures.

Thomas Woods delivered the Sunday evening talk of Mises U 2017. Woods has made quite a name for himself since I first read his Politically Incorrect Guide to American History when I was a senior in high school in 2004. He’s authored (at least) eleven or twelve books and has two popular libertarian podcasts. One is called the Tom Woods Show, which is a 5-day a week libertarian podcast, and the other is called Contra Krugman which he hosts with economist Bob Murphy, where they dissect Paul Krugman’s weekly New York Times column. I’ve heard Tom speak several times and he’s exceptionally gifted at holding an audience’s attention.

The talk was entitled “What I Learned From Murray Rothbard.” Murray Rothbard was a student of Ludwig von Mises and a tremendously influential economist and libertarian. Where Mises was a classical liberal, however, Rothbard was an anarcho-capitalist. He believed in the complete dismantling of the state apparatus and the replacement of all government services with voluntarily funded, private firms, enterprises, services, charities, communities, and networks. Consequently, he was an extreme critic of the American warfare state and of the corporate interests which benefit from overseas military adventures, nation-building, and entangling alliances. Rothbard was a phenomenally productive academic. He published books and papers on economics, ethics, history, economic-history, American politics, political philosophy, and foreign policy. He died in 1995, but his unpublished works and archives are still being released.

This talk wasn’t just a rundown of Rothbard’s political and economic views. Woods shared a personal account about how as a college student he first met the man at Mises U 1993. Rothbard delivered the opening lecture. He came out to the podium and explained, rather immodestly, that he was the “world’s foremost expert” on the Panic of 1819 – not that there was much competition, “since I’m the only one who’s ever written a book about it!” Murray joked and laughed. A second story involved the day Jeffrey Dahmer was killed in prison. That day, during an academic talk, Murray sat down next to a young Tom Woods, leaned over, and in his loud, nasally New York accent proclaimed, “Did you hear about Dahmer?! They got him!”

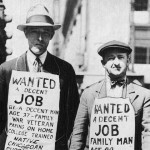

Rothbard was an economist by trade, a prolific writer, and published a great number of technical economic papers and books, including his magnum opus Man, Economy, and State. However, he also wrote extensively on American political and economic history (which includes a four volume, 1,500 page history of colonial America). The first book I ever bought of Rothbard’s was America’s Great Depression, where he outlines how the Federal Reserve’s meddling monetary policy caused the boom of the 1920s and the crash of 1929 and, if I remember correctly, also revisits the myth of Herbert Hoover as a non-interventionist free-marketeer, instead showing that Hoover was an advocate of state economic interventions and further documenting how his activist response to the crisis made matters worse. Rothbard also took on the various 19th century panics and business cycles in his A History of Money and Banking in the United States, applying Austrian Business Cycle Theory to explain how these episodes were the product of non-market state interventions.

Woods relayed the story of a 100-page indictment Murray wrote of an old run-of-the-mill American history book, not for bias, but for omissions and confusions and imprecision. In this review, a hilariously passionate Rothbard called the Land Ordinance of 1785 a “dictatorial intrusion into the Western region, which set too high a minimum land sale and price, thus restricting settlement, and also enforced rectangular surveying, thus forcing the purchase of submarginal land within an otherwise good rectangle, instead of conforming as in the Southern methods of surveying to the natural topography of the land in question.” Who formulates a fiery opinion over that? This tale is to some degree an illustration of the breadth of Rothbard’s historical knowledge, as most folks aren’t even aware of the Land Ordinance of 1785, let alone so well acquainted with both it and economic theory that they’ve staked a flag on it as some critical issue of justice.

Woods told of how Rothbard’s influence and writings moved his ideology from “moderate Republican,” which Woods described as being “basically wrong on everything,” to libertarian. The basic Rothbardian moral analysis of the state: If a particular undertaking isn’t morally acceptable on a personal/individual level, how can it then become so simply because a democratic majority says it is? Does, for example, the forcible expropriation of money or property – called theft when committed by a private person – suddenly become morally permissible because a majority approves it? For Woods, a Catholic, this line of thinking was persuasive and as a young man put him on the road to libertarianism.

Woods speech was Rothbardian beyond the anecdotes, book titles, and ideas. He took shots at the Beltway libertarian crowd with whom Rothbard had some infamous falling-outs and, in Woods telling, would rather get an invitation to a New York Times cocktail party than take an unpopular libertarian position against the state, the establishment, the banking system, and war. He didn’t name names, but I think the folks at CATO can read between the lines.