American governors and presidential candidates are calling for the United States to reject immigrants and refugees. A leading candidate is beating the drums for an incipient police state, complete with informants on every block. Many of these voices claim the Christian faith as their own.

The signs are clear: it’s high time we talked about Rahab.

What is a Canaanite prostitute from Jericho doing right next to “our father Abraham” as an example of “faith with deeds” in the most famous passage of James’ letter (2:14-28)? Shouldn’t Sarah or Ruth have that place of honor among women? Shouldn’t James point to Moses or Elijah instead?

Image of this non-prostitute model with a penetrating gaze by BestPhotoStudio on Shutterstock.com

The short answer: Rahab is a model of faith in action because she risked her life to protect the spies Joshua and Caleb from discovery and execution by the soldiers of Jericho. She stood against bloodshed and showed loyalty to vulnerable people, and that is the kind of faith James wanted to commend.

But why did James want to commend Rahab’s act of faith? And why should American Christians care about our interpretation of James on this Thanksgiving weekend in 2015, amid the Islamic State’s threats, the Syrian refugee crisis, and partisan political grandstanding?

We misread James and mangle our ethics

The answers to those questions require that we address a longstanding defect in our interpretation of the Bible and, therefore, in our contemporary Christian ethics. We, the whole church for many generations, going back at least to the Reformation and earlier, have been misreading the epistle of James and impoverishing our understanding of faith in action. Now would be a good time to get it right, to let the agony of James’ world soak into our bones, and to remind us how perfect love casts out fear.

Our reading is missing a crucial lens: that James has a coherent theme driven by concrete, real-world events. Just as I Corinthians is a response to an incestuous relationship and Philemon is a response to an escaped slave, James is a response to a horrific event or pattern of events. If we discipline ourselves to apply a lens that expects to find coherence in spite of our historical and cultural distance, we can readily find it.

Yet we—and in “we” I include most of our leading theologians and scholars, with all our literary and historical expertise—have read James’ letter as a disjointed collection of pastoral proverbs, warm-hearted snippets of pastoral wisdom beneficial mainly for our personal piety. (A rare exception who reads James with an expectation of coherence is Lutheran scholar David Scaer.)

When laypeople are asked what the letter is about, we are most likely to remember “faith without works is dead” (2:20), and we argue most about how to reconcile that idea with “salvation by grace through faith.” We reduce “taming the tongue” (3:8) to “don’t gossip or say bad words,” and we think of “resisting the devil” (4:7) as saying a tearful prayer for aid in resisting the temptation to lust or gluttony.

But if we read with the lens of internal coherence, we find that James is not that kind of letter. Not at all. James is the kind of letter a church leader writes when rebel soldiers slaughter innocents, when believer betrays believer, when borders are contested, and when the rich use money to buy the persecution of the poor. James is about murder and mercy, life and death, blood and betrayal.

James likely writes in the late 40s AD, probably not long after Stephen’s stoning, Saul’s brutal but legally-sanctioned persecution, and the diaspora of Jewish Christian believers. It was a time when religious and nationalist leaders and movements jockeyed for position, trying to duck below the awesome power of Rome while clawing a way out of the suffering of the masses of poor and slaves.

James is a timely letter for today, for a time of Islamic terrorism, rumor- and fear-mongering, racism, ideological puritanism, and moral confusion.

The letter from James is emphatically NOT a curio shelf of moralistic rhetorical knickknacks about personal piety and morality. On the contrary, it is a jeremiad, speaking clearly with the voice of Jesus and the prophets, indicting the self-righteous hypocrisy of religious leaders who extol their own national pedigree and sexual purity while backstabbing and cheating and persecuting the vulnerable and the poor.

James insists on subordinating personal piety to collective mercy. That is why a pagan prostitute is compared favorably to Abraham: her story proves that God honors mercy over morality. Her adulterous life is redeemed by her prevention of a murder. The mention of Rahab in 2:25 follows directly from 2:8-11, where James writes that avoiding adultery does not excuse complicity in murder.

A letter from an angry king to traitors among his subjects

James is likely the first, oldest text of the New Testament, written by the first major leader of the church in Jerusalem to Jews and Jewish Christians all over the world. Tradition and contemporary scholarship agree that the most likely author was Jesus’ brother, identified by Paul as a leader of the church in Galatians 1:19-20. In verse 20, Paul essentially says, “dude, I’m not lying, I met James!”—evidence that the meeting was so distinct an honor that Paul had to defend his claim. Why? In a culture very interested in royal genealogy (Matthew 1:1-17, Luke 3:21-38), James, as Jesus’ brother, was the leader of the church and the rightful heir to the throne, the true king of Israel! This claim is not essential to the interpretation below, but reading James imaginatively as a letter from a rightful king helps to reveal its urgency and coherence.

As a pagan prostitute, Rahab is contrasted as an unlikely candidate for virtue with the conventional appeal to Abraham’s righteousness. Yet Rahab is one of Jesus’ and James’ honored ancestors in the royal line of Israel (Matthew 1:5). James holds up his own family as a model, drawing on the history of Israel’s royal line.

The key to understanding the narrative coherence of James is revealed, as in every riveting, epic story, in the climax near the end of the letter, in chapter 5, verses 1 to 6:

1 Now listen, you rich people, weep and wail because of the misery that is coming on you. 2 Your wealth has rotted, and moths have eaten your clothes. 3 Your gold and silver are corroded. Their corrosion will testify against you and eat your flesh like fire. You have hoarded wealth in the last days. 4 Look! The wages you failed to pay the workers who mowed your fields are crying out against you. The cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord Almighty. 5 You have lived on earth in luxury and self-indulgence. You have fattened yourselves in the day of slaughter. 6 You have condemned and murdered the innocent one, who was not opposing you.

If we read this passage through the lens of coherence, these verses are not a litany of unrelated sins; they are telling the story of rich landowners protecting themselves from religious persecution by turning traitor, accusing their farm laborers of being traitors to Rome in order to scapegoat them and get richer by withholding their wages. James is righteously angry because of the mass murder and persecution of fellow believers by wealthy people who were claiming to serve God as children of Abraham while using their power to expand their wealth. The unpaid wages “cry out” like Abel’s blood from the ground because they are covered in blood. The “day of slaughter” they fatten themselves in is the day the laborers were executed.

We misread the letter if we do not keep this background of bloody, traitorous crime constantly in mind. It weighs on James’ mind, and every word of the letter is colored by his righteous anger, even when he counsels against human anger (1:19-20).

Taming our tongues is a matter of life and death

Once we have the key, the thematic coherence of James is much easier to follow throughout the letter. James demands that we reckon with the violent consequences of our self-serving words and actions. He condemns self-righteous finger-pointing. He demands we put the interests of the weak above our own.

The theme of reining in the tongue running throughout the letter is not about avoiding four-letter profanities, lewd talk, or petty office “backstabbing.” It’s about talk that leads to literal stabbings, along the lines of the “loose lips sink ships” posters of World War II. The Greek word for devil is diabolos, accuser or slanderer. We resist the devil (4:7) by refusing to be devils, by not accusing and slandering others (4:11). We should keep a tight rein on our tongues (1:26) by not using the sins of fathers in the courts to get them condemned, so that their wives become widows and their children become orphans; instead, we serve and protect the many widows and orphans already produced by war and violence.

When James says that “every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father” (1:17), it’s not a sweet saying to put on flowery greeting cards or refrigerator magnets. The previous verse, “Don’t be deceived” (1:16) should convince us it’s a warning, not an encouragement. James does not use a common Greek word for a physical gift (doron) nor for a spiritual gift (charisma). Instead, he actually uses two rare Greek words with pecuniary connotations: “Every good quid-pro-quo donation [dosis] and every perfect bonus [dorema].” The message is to resist the deception of “free” payoffs and bribes from rich, influential patrons. These payoffs are inducements, temptations:

- to be double-minded or traitorous (1:8);

- to forget that the person in the mirror is also a member of a vulnerable, persecuted religious minority (1:23-25);

- to show favoritism to the rich (2:1-13);

- to neglect charity out of greed (2:14-17);

- to curse human beings (3:9);

- to indulge our envy and selfish ambition (3:13-15);

- to quarrel and fight, befriend the world, slander our fellows, and boast about our success (chapter 4);

- and ultimately to betray poor fellow believers into imprisonment and death (5:1-6).

James likely alludes here to Judas’ betrayal of Jesus for the infamous 30 pieces of silver (Matthew 26:14-16), the ultimate treason against God himself; he means to shame his readers with the realization that they are committing the sin of Judas.

When James writes that “sin, when it is full grown, gives birth to death” (1:15), he does not have in mind a hairsplitting theological distinction between physical and spiritual death. He means that accusations, slanders, and curses cause death, the death of the accused, and their blood is on our hands. When James says that the tongue is a “world of evil” (3:6) “a restless evil, full of deadly poison” (3:8) with which we “curse human beings,” (3:9), he’s not talking about saying “damn” or even about speaking heresy. He’s talking about uttering words of accusation and judgment that ruin lives and lead to bloodshed.

Mercy triumphs over judgment

During our long obsession with how to read “faith without works is dead,” we have been prone to bitter strife and infighting among Christians over who has the proper theology. Nothing could be more at odds with the purpose of chapter 2, which begs us to stop the strife and make peace with each other.

The theological center of James is not “faith without works is dead” (2:17), but “mercy triumphs over judgment” (2:13), words that set the stage for the text about faith and deeds. Immediately after reminding us that murder is sin, James writes:

12 Speak and act as those who are going to be judged by the law that gives freedom, 13 because judgment without mercy will be shown to anyone who has not been merciful. Mercy triumphs over judgment.

Like everything else in James, this triumph of mercy over judgment is not a gentle, subtle event. “Triumphs” is a Greek power verb (katakauchomai, to “boast against” or “exult over”) with a connotation of unsportsmanlike gloating and dragging the prisoners down the main boulevard in chains. Mercy wins because God makes the rules, and God grants mercy total victory over self-righteousness and finger-pointing.

Being judgmental does not have a pretty future. Mercy’s going to be a cruel victor. It will surely feel like burning coals heaped on our heads.

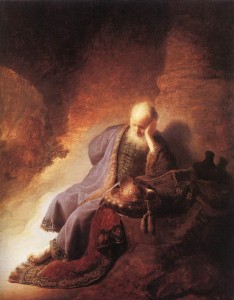

Tissot, The Taking of Jericho from Wikipedia Commons

Make it real: repent, and show mercy

At work and church, in politics and business, are we like Rahab? Do we forgive mistakes, overlook faults, offer relief, protect the vulnerable, and repent of our own errors, sins, crimes, and atrocities? Do we attack the plank in our own eye?

Or are we like the bloodthirsty, self-indulgent people of Jericho, whose walls will fall? Do we point self-righteous fingers at others, boast about our own success, use our wealth and power to afflict and slander others? Do we damn the speck in the eye of the partisan, the addicted sinner, the homeless refugee?

“Judgment without mercy will be shown to anyone who has not been merciful. Mercy triumphs over judgment.” (James 2:13)

God have mercy on me. God have mercy on us all.

Please join in the discussion on our Facebook page. And please take action and show mercy as best you can. Please consider donating and advocating for Syrian refugees in the US (through Bethany Christian Services, for example) and overseas (through World Renew, for example). Advocate for immigrants through the A Blessing Not A Burden Campaign.

Coming soon: a discussion of Team of Teams by General Stanley McChrystal. Not long after that, “Should the church be run like a business? A surprising answer from sociology.”

Stay in touch! Like Charting Church Leadership on Facebook: