Introduction

In my first post I described a problem that has plagued the church. The problem is this bifurcation of the church and the academy. What used to be a single position of leadership in the church, the pastor-theologian, is now two separate and often disconnected positions. It is not my desire to pin blame on anyone one party for this problem. Rather, it is the goal of this post to examine (briefly) historically the relationship between academic theology and the church. It is my hope to recover an ancient vision of the pastor-theologian for both the church and the academy today. For, when one suffers, both suffer. What follows is a brief reflection on the historical connection between the church and the academy.

Theological Reflection in the Apostolic and Patristic Era

Theology as a formal academic discipline did not exist until the rise of the medieval university in the 12th century (see Pillay and Womack 2018). This does not mean that theological reflection did not exist until then. Rather, from the earliest periods of the Apostolic era, informal theological reflection was happening. By informal I am referring to the rational reflections of the early church on its practice of faith. Ultimately, it is this informal reflection that births formal academic Christian theology (Pillay and Womack. 2017, 2).

Following this informal theological reflection in the Apostolic period is the rise of a more formal reflection, characteristic of the Patristic period. During this time theologians such as Justin Martyr and Irenaeus wrote helping their local congregations stand against false teaching. They did this through their theological writings using formal reason and faith practice in making their arguments. Their theological reflection was done in the context of and for the sake of the local church.

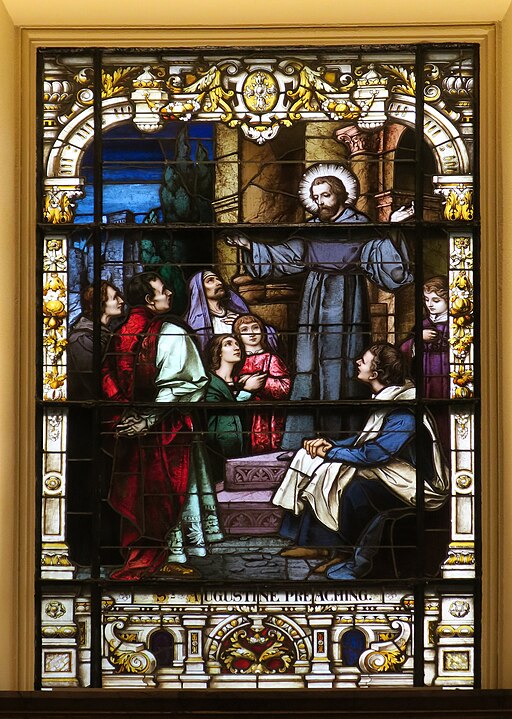

Theological Reflection in the Post Constantine Era

In the 4th century, The Roman emperor Constantine brought significant change to the life of the church. Within a decade, the church went from persecuted to powerful. The legalization of Christianity and its subsequent rise in popularity brought with it the “freedom to become formalized institutions” (Pillay and Womack. 2017, 2). It is during this time that Augustine lived and wrote. He wrote in the context of the Arian and Donatist controversies, and the fall of the Roman empire. Among his writings are books, letters, and sermons all written for the purpose of helping “the Christian community continue to function amidst the fall of Rome” (Pillay and Womack. 2017, 5).

Augustine was not alone during this time. Rather, those such as Ambrose, Gregory of Nazianzus, and many others worked as well to serve the church. In fact, Pillay and Womack argue, it is at this time “we see a minister with a high level of education dealing with the daily struggles of the congregation, and pioneering academic theology to the benefit of both institutes” (Pillay and Womack. 2017, 5). Thus, while theological reflection was becoming more formalized and academic during this period, theologians during this time remained wholly committed to the life of the church.

The fall of the Roman Empire caused a dramatic change to life in Europe at the time. It is in the wake of the Empire’s fall that the monastery sees its rise. Through the formalization of monasticism with the work of those such as Scholastica and her twin brother St. Benedict, the monastery became the place in which clerical training took place including theological training (Bevans, An Introduction to Theology in Global Perspective). It might seem like this is the first instance that a riff between the academy and the church takes place since we often think of monasticism as removed from society. However, as Hiestand and Wilson argue, “both church and the monasteries saw the monasteries as an extension of the church and an aid of the church’s mission” (Hiestand and Wilson, 30).

Theological Reflection in the Medieval University

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the modern university arises. The medieval university would have a lasting impact on the practice of theology. During this time, theology began to move out of the church and into the university placing an emphasis on the use of reason. The focus of theology during this time began to expand. However, theological study was still the work of the church as most universities were actually started by the leaders of the church (Olesko, “University” in The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science).

During this period their arose intellectual debate among theologians such as Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus, and William Ockham. They debated concerning the use of secular philosophy by Christian theology. This lead academic theology, according to Vos, to lose its focus on the needs of the church (Vos, “Scholasticism“). Thus, Pillay and Womack argue that the rise of the university begins to change the focus of academic theology from the needs of the church to philosophical disputes (Pillay and Womack. 2017, 8).

As theology became rooted more exclusively in the university, the church became more unsatisfied; unsatisfied with the application of theology being produced within the university. Thus, from this period to the present, the rift has seemingly only been growing until recently with the work of those such as Vanhoozer and Heistand and Wilson who are working to recover a vision of the pastor-theologian.

Conclusion

The church and the academy have become unmoored and slowly drifting away from each other. The academy has lost its emphasis on the needs of the church. The church has lost its desire for theological reflection. What has been briefly explored in this essay shows us how academic theology has gone adrift and ultimately failed the church. This is not to say that the academy has produced nothing of worth during its time adrift. However, the church and the academy need each other. Thus, we must recover the ancient vision of the pastor-theologian for the sake of the church and the academy. This is what will be explored in the next and final post in this series.