Buddhism embraces a different worldview than most Western religions.

Buddhism developed in response to Hinduism, which could be rigid and ritualistic. Siddhartha Gautama (now called the Buddha) was a seeker who found enlightenment under a bodhi tree, where he attained liberation from samsara, the cycle of suffering.

Buddhism is grounded in the Buddha, the dharma (teachings) and the sangha (community.) On his deathbed, the Buddha reportedly instructed his followers not to blindly follow any leader (even the Buddha) and to scrutinize any teachings (even the Buddha’s teachings.)

The Buddha is not a god, but a human being who realized his connection to everyone and everything. He developed a “middle way” between self-indulgence and self-mortification to alleviate suffering. Buddhism is based on impermanence, imperfection, and selflessness.

Buddhism

The Buddha taught that everything is characterized by impermanence, so attachment produces suffering, primarily related to fear about the future and regret about the past. Here and now, the grass is growing and the sun is shining, despite our fears and regrets. Some might think that “detachment” means indifference. But, Buddhism is a compassionate tradition, and Buddhists care about all sentient beings.

Of course, we cannot change imperfection or eliminate the pains of death and illness and old age, but we can reduce the suffering associated with them. Buddhists reduce suffering by meditating, which involves clearing the mind, glimpsing the True Self (which is no-self), perceiving the Universe as it is, and recognizing our connection to the Universe.

In Buddhism, the idea of self is not central. Buddhists seek “no-self” or selflessness, avoiding attachment to the idea of a separate self and thereby reducing suffering. The notion of “emptiness” is related to the notion of no-self. When thinking about emptiness, it helps to define emptiness as “without distinction or separation,” rather than “without mass or energy.”

How can we have no-self when we live in different bodies, respond to individual names and occupy unique places in space and time? The egoic self is a construct, which is ephemeral, not eternal. In the East, some practice self-inquiry, realizing that we create images of our selves and others’ selves. As Christian mystic Thomas Merton wrote, “Most of us live lives of self-impersonation.”

This worldview is very different from the worldview of religions such as Christianity, where the idea of self is central. Here, God is personal. Christians hope to develop a personal relationship with God, to embrace personal responsibility and to attain personal salvation.

Some see Buddhism, particularly Zen, as a philosophy, not a religion. There are Buddhist Christians, Buddhist Jews and Buddhist humanists. For example, my Zen teacher is a former Jesuit priest and a well-known scholar of comparative religions. He is a practicing Catholic.

Dhyana, Chan, Zen

Buddhism (like many traditions) is practiced by different people in different ways. The lineage that became Zen began in India as dhyana, which refers to meditation. Buddhism migrated to China, where it absorbed influences from Confucianism and Taoism to become Chan. Then, it migrated to Japan, where it absorbed influences from the Samurai culture to become Zen.

In the last 100 years, Zen migrated to the West, where it is absorbing influences from Western culture to become relevant and timely here. Zen is still adapting to meet the needs of 21st century Western practitioners.

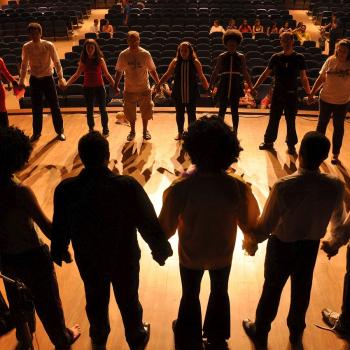

Many Eastern traditions rely on one-on-one transmission from teachers. A Zen teacher is primarily concerned with the student’s practice. Practice consists of meditation and (sometimes) koan study. Koans are paradoxical statements meant to prompt intuitive understanding. Zen practice is intended to help students to realize the connectedness of everyone and everything.

Zen is experiential, not intellectual. The Buddha was reportedly unconcerned with questions about God or the meaning of life or the afterlife, which he considered speculative. To the Buddha, we cannot know the answers to these questions, and we might not live our lives differently, even if we did know the answers.

Realizing, Not Attaining or Seeking

In Zen, there is a saying, “Do not seek the truth; only cease to cherish opinions.” Zen is about realizing, not believing or attaining or seeking. There is nothing to believe that is not speculation. There is nothing to attain, and there is nowhere to seek. So, we can ‘call off the search’ when we can let loose of our speculative beliefs, unchallenged doctrines, and untested presuppositions, to see things as they are.

This worldview is very different from the worldview of religions such as Christianity, which emphasize believing in speculative doctrines, attaining eternal salvation and seeking a personal relationship with God.

Buddhism embraces a different worldview than most Western religions. In coming weeks, we will explore the principles of Zen practice.

The Way is a Silver winner in the 2024 Nautilus Book Awards in the Religion/Spirituality of Other Traditions category.

If you want to stay up to date on the latest from You Might Be Right, simply subscribe with your email.