What is Creation?

ST 2002

What is creation? Is it the equivalent of the cosmos? Does the very word, creation, imply a transcendent Creator?

Our ecotheologians and ecoethicists tell us we should care for creation. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America once issued a Social Statement: “Caring for Creation.” Why should we care? What is creation, anyway?

In another Patheos series of posts on economics and the common good, I give voice to the underlying anxiety that the global economic system is destroying our planet’s fecundity. Should we be worried? How might understanding the natural world as God’s creation affect the way we think?

‘Nature’ versus ‘Creation’

If nature is a cold word, then creation is a warm word. When we study the physical world scientifically, it is nature that we study. But, nature points beyond itself. “This is a major theme of Christian theology–that the natural world, while wonderful in itself, offers a way to begin to discern the glory of God,” says theologian Alister McGrath at Oxford (McGrath 1998, 208).

Our term, creation, implies a Creator. More. That Creator abides with us. Loves us. Redeems us. “In the Judeo-Christian tradition,” says Pope Francis, “the word ‘creation’ has a broader meaning than ‘nature’, for it has to do with God’s loving plan in which every creature has its own value and significance.” (Pope 2015).

Can Bible-based creation and science-based creation find concord? Yes, says Lorence G. Collins, when synthesizing the Bible’s three tier universe with Big Bang. Collins appeals to the Two Books model just as did Galileo: nature tells us about God the creator and the Bible tells us about God the redeemer.

Still we ask: how do we put together these components: nature? Creation? Creativity? God? Not-God? Redemption? Time and Space? Eco-ethics? Well, let’s look at some alternative conceptual models that we find in science, Buddhism, mythology, Big History, Hinduism, panentheism, feminism, and orthodox Christianity. Then, I’ll tell you what I think.

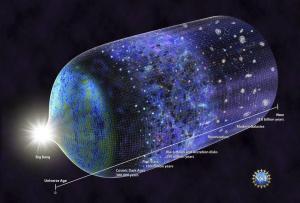

Cosmos with No Creator: Science

For our scientists, nature is the product of the Big Bang.

When the Big Bang banged 13.82 billion years ago, both nature and history had their beginning. At the very beginning, everything in physical reality was packed densely. It was hot. Then, like a bomb, it exploded. It inflated. Then, it expanded very rapidly and became massive. Gradually, as it cooled, the universe began to differentiate into particles and eventually galaxies and star systems. The cosmos evolved. It’s still expanding and still evolving and will continue to do so for another 65 or 100 billion years before it cools into a frozen equilibrium.

No divine creator belongs to this creation story.

A variant of this creation story is the multiverse theory. Deterministic cosmologists believe that every potential becomes actualized. At the point of actualization, a new universe is created. This means that we now have more universes than Florida has mosquitoes.

No divine creator belongs to this creation story either.

Creation with No Beginning: Buddhism

For the Buddhist, the key term is, co-dependent co-creation. There is no beginning. Or end. Rather, creativity is an ongoing creative co-arising of finite things in relentless process. It’s called: pratītyasamutpāda. Individual creatures come into existence and pass out of existence. But, pratītyasamutpāda continues. Here are Matthieu Ricard and Trinh Xuan Thuan.

“All religions and philosophies have come unstuck on the problem of creation. Science has gotten rid of it by removing God the Creator, who had become unnecessary. Buddhism has done so by eliminating the very idea of a beginning” (Ricard 2001, 31).

No Creator God. No beginning. Just ongoing creativity.

Creation and Kingship: Mythology

Our pre-scientific ancestors told myths about creator gods. Here is my definition of myth: a myth is a story of how the gods created the world, or a part of it, in the beginning, in illo tempore [the time before there was any time], that explains why things are the way they are today. This definition summarizes the extensive research on myths in archaic cultures pursued by Mircea Eliade (Eliade 1957). Such a myth is clearly archonic—that is, today’s reality is determined by its origin.

Conveniently, myths such as the story of the creation of Egypt by the gods Osiris and Isis concluded with justification for the Pharaoh’s rule on the throne. The teller of the myth typically comes out to be the crown of the creation story.

Creativity in Evolution: Big History

Proponents of the new field of Big History are willing to turn Big Bang science into a modern creation myth that explains everything of meaning to the human race. The idea of creation here is not connected to a divine creator. Rather, creation is an expression of nature’s creativity and, especially, human creativity.

Big History is in the myth business. The Big Bang and the history of evolution constitute Big History’s myth. Curiously, the truth of the myth is allegedly found in its belief, not in its empirical evidence. This is what big historian David Christian says. “So, the strongest claim we can make about the truth of a modern creation myth is that it offers a unified account of origins from the perspective of the early twenty-first century“ (Christian, 2004, p.6).

There is no divine creator in this scientized myth.

Creation as Brahman’s Self-Differentiation: Hinduism

The ancient Upanishadic sages asserted that all things are only one thing. That one thing is Brahman. Actually, Brahman is not a thing. To be a thing, a thing has to be distinguishable from other things. But Brahman is not distinguishable from anything. Rather, it is the underlying reality that makes thinghood possible. Brahman is fullness, the unity underlying all plurality. What we experience as the multiplicity of created things is the self-differentiation of Brahman (Peters, God in Cosmic History: Where Science and Big History Meet Religion 2017).

A Hindu can be both a pantheist—believing all things manifest the one divine reality—and also a polytheist—affirming many gods. The many gods, accordingly, are each a manifestation of the one Brahman. Hindu theologian, Rita Sherma, observes that supreme divinity is most importantly manifested in three divine figures: Shiva (Śiva), Vishnu (Vișṇu), and Mahadevi (Mahādevī) (Sherma 2017).

Hindus are finally mystics. Your and my spiritual task is to wake up and realize that each created thing—including our own self or atman—is actually Brahman.

The World as God’s Body: Panentheism

The panentheist holds that the world is God’s body. In the case of process philosopher, Alfred North Whitehead, creation is like the body and God is like the mind. They are interdependent yet distinct.

On the one hand, for all panentheists the being of the world is dependent on God while the being of God is dependent on the world. Yet, there is more to God than the world alone. The world does not exhaust the being of God. Many feminist theologians like the analogy: the world is God’s body.

There is no beginning of creation in panentheism. Only creativity within an everlasting world process.

Creation as God/ess’ Body: Feminism

Gayle Berry

The metaphor—the world is God’s body—appeals to feminist theologians. Feminists typically de-gender the divine. More importantly, the image of the divine becomes a prompt for ethical responsibility, especially ecological responsibility. Moral action is both creative and redemptive. Here is the late Rosemary Radford Ruether.

“The God/ess who underlies creation and redemption is One. We cannot split a spiritual, antisocial redemption from the human self as a social being, embedded in sociopolitical and ecological systems. We must recognize sin precisely in this splitting and deformation of our true relationships to creation and to our neighbor and find liberation in an authentic harmony with all that is incarnate in our social, historical being. Socioeconomic humanization is indeed the outward manifestation of redemption” (Ruether 1983, 215-216).

Creatio ex nihilo: Orthodox Christianity

“God by the power of his Word and Spirit created heaven and earth out of nothing,” exclaims the Reformer, John Calvin (Calvin 1960, I,xiv,20, 179-180). The orthodox Christian tradition—both orthodox and Orthodox—is that God’s original creation was out of nothing, creatio ex nihilo.

This means time and space came into existence at the beginning, at the moment when God spoke, and things began to happen. Here’s Orthodox theologian Andrew Louth.

“Creation out of nothing does indeed mean that the created order does not flow from within God’s being, as it were, as some kind of extension or emanation of his being, but it does not mean that creation is remote from the divine. On the contrary, God is intimately present to all his creatures” (Louth 2013, 40).

This means, among other things, that no aspect of created reality can be fully explained without reference to its Creator God, according to Roy Clouser at the College of New Jersey.

“All the entities found in the universe, along with all the kinds of properties they possess, all the laws that hold among properties of each kind, as well as causal laws, and all the precondition-relations that hold between properties of different kinds, depend not only ultimately, but directly, on God” (Clouser 2006, 12).

Both deists and theists are likely to embrace creatio ex nihilo. What the deist says is that God created the world in the beginning and then went on vacation to Acapulco. The deistic deity no longer intervenes in cosmic processes. The laws of nature govern without divine intervention.

According to the theist, in contrast to the deist, God does not abandon the creation. God is not on vacation. Rather God supplements creatio ex nihilo at the beginning with an ongoing providential presence. This providential activity many theologians call, “continuing creation” or creatio continua.

Creation and Creationism: Answers in Genesis

Don’t confuse creation with creationism. The latter adds a “…ism” to our word, creation. Today’s creationists reaffirm creatio ex nihilo, to be sure. Then they add a specific interpretation of Genesis 1:1-2:4a. Here is Ken Ham of “Answers in Genesis.”

“God created “the heavens and the earth” fully formed and functioning in six days, 6,000 years ago, around 4004 BC. The context of Genesis 1, as well as other places in Scripture, makes it clear these days were ordinary, 24-hour days. God’s original creation was perfect, with no death or suffering.”

The Cosmic Scope of Creation: Astrotheology

How big is God’s creation? Eco-ethicists have been striving to persuade us to become geocentric rather than anthropocentric. I laud Whitney Bauman’s planetary thinking, for example. Our moral maxim: treat Planet Earth as our only home! There is no Planet B. So, we had better care for Planet A.

But, I ask: what about cosmic consciousness? What if we have space neighbors? What if we share our solar system with microbial life on Mars or Titan? What if we share the Milky Way Galaxy with an intelligent civilization on an exoplanet? And, what about the cosmos beyond our galaxy? Can we transcend geocentrism? Yes, affirms theologian and ethicist John Hart. We should orient our ethics around a “cosmic commons,” Hart claims.

Here at the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences in Berkeley, we’ve been developing a new accent in the field of astrotheology. Try this for a definition of astrotheology, namely, God’s creative and redemptive work is cosmic in scope.

“Christian Astrotheology is that branch of theology which provides a critical analysis of the contemporary space sciences combined with an explication of classic doctrines such as creation and Christology for the purpose of constructing a comprehensive and meaningful understanding of our human situation within an astonishingly immense cosmos.”

Amended Creatio ex nihilo: Creation from God’s Future

At the gracious invitation of the editors of HTS (Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies), an open access journal, I’ve just published a manifesto of sorts on the doctrine of creation. The title? “Can We Locate Our Origin in the Future? Archonic versus Epigenetic Creation Accounts.”

I’ve been refining the concept of proleptic creation—according to which neither the cosmos nor you or I will be fully created until we are redeemed—since my very first work on the topic, Futures—Human and Divine, in 1978 (Peters, Futures–Human and Divine 1978). The pivotal thesis is that God creates from the future, not the past. This thesis is refined and reiterated in the most recent edition of my systematic theology, God—The World’s Future (Peters, God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era 2015).

If at this moment you’ve become intrigued with this topic, I recommend you click over to the more detailed article, “Can We Locate Our Origin in the Future? Archonic versus Epigenetic Creation Accounts.” If you’re lazy or partially bored, then read the summary in the next few paragraphs.

We will not be created until we have been redeemed

“To be human means to be in the world, to have a history, and to share the physical life of the cosmos,” contends Kristin Johnston Largen (Largen 2021, 191). There is a problem, however. The problem with this sharing the history of the cosmos is the problem of sin, evil, and suffering. This is the problem of the free human self. The problem of selfishness. The problem of emphasizing the fragmented part at the cost of harmony to the whole.

With sin and its accompanying estrangement in mind, we can view the epigenetic understanding of God’s creative process as one of complementarity, synthesis, and renewal. As Augustine makes clear, our deepest personal aim is to center our lives on God and, in turn, center ourselves in the whole. Such is the fulfillment of human destiny. To assert oneself in resistance against this destiny constitutes sin and produces evil. “Evil arises,” writes Reinhold Niebuhr, “when the fragment seeks by its own wisdom to comprehend the whole or attempts by its own power to realise it” (Niebuhr 1941, 1:168). Will evil last forever?

The creation as we know it today groans in travail, awaiting the birth of a healed cosmos and a healed soul. “The end is eternal life. For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Romans 6:22-23). The end is both finis as conclusion and telos as goal to be fulfilled.

“This double connotation of end as both finis and telos expresses, in a sense, the whole character of human history and reveals the fundamental problem of human existence. All things in history move towards both fulfillment and dissolution, towards the fuller embodiment of their essential character and towards death. The problem is that the end as finis is a threat to the end as telos….The Christian faith understands this aspect of the human situation….it is not within man’s power to solve this vexing problem” (Niebuhr 1941, 2:287).

God alone saves. God saves by absorbing the estranged parts into a healing whole, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Emergence, Holism, Redemption, and New Creation

South African systematic theologian Klaus Nürnberger illuminates eschatological redemption by shining the light of emergent holism. “The scientific theory of emergence has taught us that…any whole is something more than, and something different from, the sum total of its components. The reason is that the whole is constituted by relationships between components, rather than the characteristics of the individual components” (Nürnberger 2016, 1:19). God’s promised eschatological redemption is best understood as overcoming sin through holistic healing. “Christian eschatology is a protest of what ought to become against what has become and seemingly will become–and that in the name of a powerful and loving God” (Nürnberger 2016, 2:501).

Only when the whole of reality has harmoniously integrated all the self-oriented parts will we be able to say that God has finally created the world. Only when each of us individually has been freely integrated into the kingdom of God can God look at the creation and declare, “Behold! It is very good” (Genesis 1:1-2:4a).

Conclusion

As you can see, there are many conceptual models for understanding nature as creation. Both Big Bang and the Bible depict creation as having a beginning followed by a history with a future. The beginning looks pretty much the same in the two models. They are consonant.

But, this does not apply to the future. Whereas the Big Bang model forecasts a future in which all hot things will freeze into an equilibrium and die, the biblical vision anticipates an eschatological renewal of creation wrought by God. When it comes to the future, Big Bang and the Bible are dissonant.

But, this does not apply to the future. Whereas the Big Bang model forecasts a future in which all hot things will freeze into an equilibrium and die, the biblical vision anticipates an eschatological renewal of creation wrought by God. When it comes to the future, Big Bang and the Bible are dissonant.

Here’s what I think. Because nature is epigenetic and historical, the present moment is ontologically open to the future. Nature and history are together open even to the future of God.

I would like to say more. I would like our systematic theologians to construct a retroactive ontology with greater explanatory power than competing archonic ontologies. The initial axiom for retroactive ontology is this: to be is to have a future. It is God who calls us into being by graciously offering us and our cosmos a future.

God’s future-giving comes in two forms. Negatively, God is releasing creatures such as you and me from the chains of our origin and from recent efficient causes each moment. Each moment God lays before us a finite set of potentials, possibilities that prompt us to deliberate, decide and take action. By taking action, we liberated free creatures play a creative role. We become one efficient cause among many in the history of creation.

Positively, God makes promises. By raising Jesus from the dead on the first Easter, God promises to raise you and me as well into the new creation. Actually, more can be said here. By raising Jesus from the dead on the first Easter, God has actually begun his eschatological work of redemption. The final advent of the kingdom of God in which all estranged parts will be taken up into a transfiguring whole defines the very quiddity of what happened at Easter. Our past Easter takes its essence from its future in God’s kingdom. The Big Bang genesis of creation gains its essence from the new creation proleptically anticipated in Jesus’ Easter.

Omega retroactively defines Alpha. Omega invites each of us into the everlasting future of God’s new creation.

▓

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He previously authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted’s fictional spy thriller, Cyrus Twelve, follows the twists and turns of a transhumanist plot.

▓

Notes

[1] Catherine Keller grants that “all theologies that claim orthodoxy posit the creatio ex nihilo” (Keller 2003, 16). Then Keller proceeds to skirt orthodoxy to place the creativity not in God’s Word but rather the nothing—which is really something—out of which God’s Word fashions the cosmos. When God’s spirit sweeps over the deep, that deep has the potential to become cosmos. “But I wonder whether precisely the Genesis tehom—which implies neither pure evil nor total victimization but something more like the matrix of possibilities in which liberation struggles unfold—would not serve the current context better than the orthodox ex nihilo” (Keller 2003, 21).[2] This is the point of Rahner’s Eine Futurologische Kurzformel, or Brief Future-Oriented Creed. “Christianity is the religion which keeps open the question about the absolute future which wills to give itself in its own reality by self-communication, and which has established this will as eschatologically irreversible in Jesus Christ, and this future is called God” (Rahner 1978, 457 Rahner’s italics).

References

Calvin, John. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion, 2 Volumes. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Clouser, Roy, 2006. “Prospects for Theistic Science.” Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, 58:1 (March 2006) 2-15.

Eliade, Mircea. 1957. The Sacred and the Profane. New York: Harcourt Brace and World.

Keller, Catherine. 2003. The Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming. London: Routledge.

Largen, Kristin. 2021. “Plurality and Salvation: Possibilities in Pannenberg’s Soteriology for Comparative Theology.” In The Enduring Promise of Wolfhart Pannenberg, by ed Andrew Hollingsworth, 183-200. Lanham MA: Lexington.

Louth, Andrew. 2013. Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology. Downers Grove IL: IVP Academic.

McGrath, Alister. 1998. The Foundations of Dialogue in Science and Religion. Oxford: Blackwell.

Niebuhr, Reinhold. 1941. The Nature and Destiny of Man, 2 Volumes. New York: Scribners.

Nürnberger, Klaus. 2016. Faith in Christ Today: Invitation to Systematic Theology, 2 Volumes. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Peters, Ted. 1978. Futures–Human and Divine. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

—. 2017. God in Cosmic History: Where Science and Big History Meet Religion. Winona MN: Anselm Academic ISBN 978-1-59982-813-8.

—. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Pope, Francis. 2015. Laudato Si. http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html, Vatican: Vatican City State.

Rahner, Karl. 1978. Foundations of the Christian Faith. New York: Seabury Crossroad.

Ricard, Matthieu and Trinh Xuan Thuan. 2001. The Quantum and the Lotus. New York: Random House, Crown Books.

Ruether, Rosemary. 1983. Sexism and God-Talk. Boston: Beacon.

Sherma, Rita. 2017. Hinduism and the Divine: An Introduction to Hindu Theology. London: IB Tauris.