The empress Wu Zetian (624-705) was one of China’s greatest rulers. She is also known by the name Wu Zhao and a few others. Wu Zetian was the only woman to rule China directly, in her own name. This is particularly remarkable considering she began her imperial career as a 17th-rank concubine. Her rule saw the early years of what is remembered as a golden age in China, when China’s culture and economy bloomed. She elevated the status of Buddhism and affected the course of Chinese Buddhist history.

And it would be lovely to report that Wu Zetian was a great and compassionate humanitarian, but in truth she didn’t become China’s only Empress by being nice. Recorded Chinese history paints her as ruthless and cruel. It’s also the case that those records were kept by hyper-patriarchal Confucians who disapproved of women rulers. So perhaps we should take recorded history with a grain of salt. But this post will focus mostly on her impact on Buddhism.

Wu Zetian’s Rise to Power

At the age of 13 Wu became a low-ranked concubine in the house of Taizong (598-649), the second emperor of the Tang dynasty (618 to 907). Taizong is considered one of China’s greatest leaders to this day, and the early Tang Dynasty is considered a high point of Chinese civilization. Wu had no children with Taizong. In 649 Taizong was succeeded by his son Gaozong (628-683), who promoted Wu to first-rank consort. Wu had four sons and two daughters with Gaozong. In 655 she gained the title empress (皇后) after the previous empress was deposed. The history-recorders claimed that Wu smothered her own baby daughter, Princess Si, and persuaded Gaozong that Empress Wang had killed the baby. This brought about a wholesale purge not only of Wang but of all who supported her, including some senior ministers.

As time went on it was Wu who exercised power in the empire while Gaozong “sat with folded hands,” in the words of 11th century historian Sima Guang. Gaozong may have been unwell. But this worked out, because Wu was brilliant and decisive. “Repeatedly she outwitted opponents, stymied rebellion, defended and extended the frontiers, and launched giant dynastic initiatives,” wrote historian John Keay (China: A History, UK General Books, 2009).

After Gaozong’s death in 683, Wu became dowager empress and continued to rule through her and Gaozong’s son, the emperor Zhongzong. But then Zhongzong was deposed for disagreeing with his mother. Then she ruled through another son, the emperor Ruizong. In 690 Wu decided to eliminate the front man. She demoted Ruizong back to Crown Prince and assumed power in her own name. In this way she became China’s only empress regnant. She was deposed in a palace coup in 705, while she was ailing. It’s said she got out of bed to confront those deposing her, then went back to bed. Zhongzong was restored to power. Wu Zetian died later that year. She had been the supreme power in China for about five decades.

Wu Zetian and Master Fazang

Wu probably was introduced to Buddhism as a child by her mother, who was known to be a devout Buddhist. As empress, Wu Zetian built many Buddhist temples throughout her empire and sponsored Buddhist scholarship. Her interest in Buddhism appears to have been sincere, although it’s also the case that because her reign was strongly opposed by Confucians, she sought validation in Buddhism. She portrayed herself as a cakravartin or cakkavattin, a “wheel-turning monarch” who upholds Buddhism for her people, and a living bodhisattva, an enlightened being who has vowed to bring all beings to enlightenment.

Wu was especially drawn to Huayan Buddhism, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of all things. One of the many scholars she sponsored was Fazang (643-712), a patriarch of the Huayan school. The influence of Fazang’s commentaries and translations can be found throughout east Asian Buddhism. He was a brilliant orator and lecturer as well as a renowned writer and scholar. Wu arranged for Fazang to lecture on the Avatamsaka or Flower Ornament Sutra and to assist in a new translation of the sutra, which was published in 704. Her sponsorship elevated his reputation in China, and he in turn used his rhetorical abilities to support his patroness.

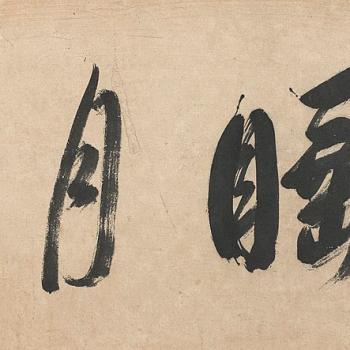

There is a Buddhist gatha, or short verse used in liturgy, called the “Gatha on Opening the Sutra.” According to legend, at least, this gatha was written by Wu Zetian after she read the Avatamsaka. I can’t vouch for this as history, however. Here is a common translation. (“Tathagata” is one of the names of the Buddha.)

The Dharma, incomparably profound and infinitely subtle,

is rarely encountered, even in millions of ages.

Now we see it, hear it, receive and maintain it.

May we completely realize the Tathagata’s true meaning.

Wu Zetian and the Great Vairocana Buddha

Vairocana Buddha is important in Huayan Buddhism as the primordial Buddha; the phenomenal universe emanates from his body. Huayan also encouraged followers to regard their earthly ruler as the representative of Vairocana. This was a belief Wu Zetian no doubt wanted to encourage also.

The Longmen Grottoes are a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Hunan Province, China. UNESCO tells us that the “grottoes comprise more than 2,300 caves and niches carved into the steep limestone cliffs over a 1km long stretch. These contain almost 110,000 Buddhist stone statues, more than 60 stupas and 2,800 inscriptions carved on steles.” Work began on the grottoes in the 5th century and continued for many centuries after. The largest grotto is called the Fengxian Temple, and the most impressive figure in that temple is a Vairocana Buddha that is more than 17 meters (about 56 feet) tall. Wu Zetian sponsored the carving of this Vairocana and led a ceremony at its dedication. And it’s said that the Vairocana was given Wu Zetian’s face.

A side note — the earliest depictions of the Buddha in China made him look plausibly Indo-Aryan, as he probably was, but by Wu Zetian’s time Chinese artists were more often depicting the Buddha and other iconic Buddhist figures as Chinese.