In the past two posts, I’ve outlined the historical background to the arguments made by David Bentley Hart in his book Tradition and Apocalypse. Hart’s starting point is the evidence of diversity and disruption found in Christian tradition from the beginning. It’s simply not true that there’s an unbroken, unchanging stream of tradition linking modern Christians to the time of Jesus and the Apostles. Rather, Christian tradition is full of conflict and innovation. Ideas central to orthodoxy, such as the Trinity, were not simply restatements of what was always believed but involved radical, imaginative leaps.

The failure of the “third way”

In light of the challenge to traditional Christianity posed by the Reformation, those Christians who remained loyal to Rome doubled down on the claim that Catholicism did represent such an unbroken stream of tradition. By the early 19th century this claim was increasingly hard to maintain, even as Protestants themselves had largely abandoned their original claims to historical continuity in favor of a radical form of “sola Scriptura.” John Henry Newman and his companions in the Oxford Movement articulated a third alternative. They claimed that Anglicanism actually represented a pure Catholicism based on the core teachings of the early Church, without the innovations of Rome.

By the time he wrote the Essay on Development in 1845, however, Newman had come to realize that this position was untenable. And this was precisely because Newman was a very good historian who recognized the discontinuities and ruptures within Christian history. (That’s not to say that he went nearly as far in that direction as modern scholars would do. I’ve heard his account of the Trinitarian controversy used as a foil for modern theories. But the Essay shows that he did have some understanding of how complex and contentious the development of the tradition was.)

Trees and acorns

Instead, Newman suggests that Christian tradition is something that develops in a manner analogous to a tree developing from an acorn. The tree may not look like the acorn, but it is still the same organism. Like many 19th century authors, even before Darwin, Newman tends to think of history in terms of biology. For him the Church is a kind of organism because it is animated by the Holy Spirit. (More on that later.) Hart is very hard on these biological metaphors of Newman’s, and I think he’s certainly right that Newman uses them to skate over difficult questions about just what the continuity of tradition really consists of.

Newman attempts to give substance to his claim of continuity by articulating seven criteria that characterize authentic developments as opposed to “corruptions.” These six are “preservation of type,” “continuity of principles,” “power of assimilation,” “logical sequence,” “anticipation of the future,” “conservative action upon the past,” and “chronic vigour.” I’m not going to go into the details of each of these, though Hart does. I’ve always found the apparent precision and technicality of Newman’s discussion here to be rather illusory. What matters, in my opinion, is the overall argument that there’s a discernible difference between changes that make an idea or tradition more fully itself and those that radically alter its character so as to constitute a break in continuity.

An argument that can prove anything?

Hart’s basic critique of Newman’s argument is that these criteria could be used to prove the legitimacy of pretty much any development. If the Arians had won, they could argue that all of these things applied to their theology. We might have an Arian Newman holding forth about the obvious violation of “type” and change of “principle” involved in the short-lived heresy of homoousianism. In this alternative timeline, Newman would no doubt have much to say about the “conservative action” of Arianism upon the first three centuries of Christian theology. The subordinationism of the second and third centuries would be seen to have found its culmination in the fuller and more rigorous work of Arius and Eusebius and Eunomius. And so on through all the criteria.

The “chronic vigour” argument is particularly open to Hart’s critique. It essentially amounts to saying that the theology that wins must have been right all along. But Hart thinks that all of the criteria really amount to the same thing in more or less disguised form. People are really good at finding continuities between their beliefs and a past that they want to claim. Their cleverness may be entirely legitimate, but it doesn’t constitute some kind of clear, objective argument for the truth of their position. Equally clever people under other historical circumstances could have made the same arguments for quite different positions. And when other traditions manage to show “chronic vigour”–i.e., when they survive attempts to suppress them–they unsurprisingly produce clever people who do just that.

Ecclesiology: an illustration of the argument

Way back in 2005, near the beginning of my blogging career, I wrote a critique of Newman as part of an intermittent dispute I was having with Dave Armstrong (now my Patheos colleague). At this point I was an Episcopalian myself. I had been seriously shaken by Newman around 1999, when I read the Essay around the same time that I read Bauer’s Orthodoxy and Heresy mentioned in my first post in this series. The combination of the two books, coming from such different perspectives yet agreeing in many ways, had destroyed forever my ability to accept some naive concept of an unchanging orthodoxy. It was clear to me that any account of tradition that worked had to have a robust account of development. But as I mentioned a few paragraphs ago, I also wasn’t very confident in the specifics of Newman’s criteria.

In the piece I linked to above, I argued specifically that an ecumenical Protestant ecclesiology was just as reasonable a development of patristic ecclesiology as Vatican II’s ecclesiology was. Neither ecclesiology was anywhere near as rigorous in its exclusion of heretics and schismatics as the ecclesiology maintained by the Fathers. Protestants and Catholics have different solutions to the problem of this apparent break with patristic ecclesiology. One solution may work better than another, but one position is not obviously a “corruption” while the other is an authentic “development.” Each position draws on different aspects of the past. Vatican II’s ecclesiology may be a more conservative development on the whole, but it’s a difference of degree, not kind.

Protestantism and development

I’d probably be more confident today than I was then in saying that yes, Catholic ecclesiology is much easier to defend than Protestant in terms of continuity with the tradition. In fact, even then I was arguing with myself–I switched back and forth regularly between more “Protestant” and more “Catholic” moods. (Honestly, I still do, but actually being in full communion with Rome does have a steadying effect.)

And on other issues, I think a stronger case can be made for Protestantism being in much less continuity with the past than Catholicism is. I’ve made that case on this blog for soteriology, for instance. I have little patience with people like Gerald McDermott (unsurprisingly a harsh critic of Tradition and Development) who argue that the Reformation was a basically conservative movement and that Luther shared McDermott’s own self-styled “Traditionism.” I don’t think all developments are equal. But I do think that Newman’s attempt to make a clear and objective distinction between “developments” and “corruptions” doesn’t work. As Hart says, it’s all an argument backwards from a preconceived conclusion. Some developments are indeed more radical than others, but sometimes the radical ones wind up becoming orthodoxy (as Hart shows in the case of the Trinitarian controversy).

Luther and Athanasius

The evangelical patristic scholar George Kalantzis once argued to me (in response to a question/comment I made of a truculently pro-tradition nature at a conference at Wheaton) that Athanasius was just as much in disagreement with “the Church” of his day as Luther was. (Or perhaps he said tradition–I can’t remember for sure.) I still think there are some important differences, but I don’t find Kalantzis’ view as obviously wrong now as I did then (around 2010 I think). Even though I’ve recognized problems with the specifics of Newman’s arguments, I’ve still been convinced by the idea that in general a true development is going to be in some discernible way more continuous with the past than a false one. Hart would argue that this just isn’t the case.

Now Hart himself clearly prefers Athanasius to Luther. Indeed, I don’t think he has nearly as much sympathy for Luther’s theology as I have. So on what basis can one say that one is “truer” than the other? This gets us, finally, to Hart’s actual argument about the apocalyptic nature of tradition. But alas, I have yet again run out of space. But there’s one last point to be made before I finally tackle the meat of Hart’s argument.

Blondel’s refinement

Along with Newman, Hart deals with the further development of Newman’s argument made by Maurice Blondel in the early 20th century. I am at the disadvantage of not having read Blondel. I have read Yves Congar, who drew on Blondel’s arguments. Indeed, the “ressourcement” or “nouvelle theologie” represented by Congar is the theology, essentially, that converted me to Catholicism. So clearly I should have read Blondel.

Hart respects Blondel as a philosopher and agrees with his dual criticism of a historicism that finds no continuity in tradition and an “extrinsicism” that blindly follows a revelation disconnected from the rational study of history. But he thinks that Blondel’s argument ultimately doesn’t work any better than Newman’s. Essentially, he argues, Blondel jumps back and forth between history and dogma, using each to explain the other in a circular fashion. I’m not going to discuss this critique in depth due to my lack of familiarity with Blondel. But one can certainly find examples of the kind of thing Hart is describing in a lot of official, moderately conservative Catholic interpretation of history today.

What is at stake here

I mention Hart’s critique of Blondel in order to underline that he’s mounting a critique not just of Newman but essentially of the “hermeneutic of continuity” that underlines moderately conservative Catholic theology since Vatican II. As I mentioned in a blog post a few years ago, there are signs that this theology of continuity is falling apart. Since the accession of Pope Francis, the voices criticizing Vatican II from the right have become more and more insistent. And at the same time, Pope Francis has (whether he agrees with them or not) liberated and emboldened those voices within the Catholic Church that would call for a greater willingness to break with tradition in the name of the Gospel.

Many of us converted to Catholicism because we hoped to find there a stability and continuity we had not found in Protestantism. So if Hart is right, the stakes are very high indeed.

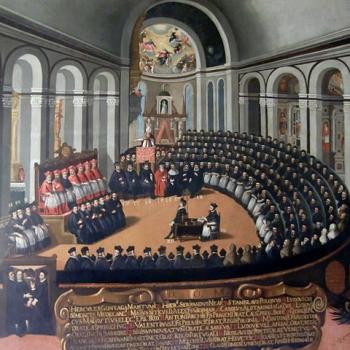

Image: Vatican II in Session, from Wikimedia Commons