This post deals with the Gospel for the Ninth Sunday after Trinity (a.k.a. the Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time), as celebrated on 28 July, 2024 (Year B, week 17).

The Bread of Life Discourse

Beginning this past Sunday, and lasting I believe through the final Sunday of August, we are back in the Fourth Gospel, reading about the first of the two miraculous feedings and the homily containing one of Jesus’ famous “I am” statements, I am the bread of life. For reasons that are probably obvious, this has always been understood by Catholics to be about the Eucharist. Other things as well, maybe, but definitely about the Eucharist.

It’s a text that’s had a lot of ink spilled over it. Ink, and also—in an irony that would be funny, if it did not reek of hell—not a little blood, in those countries (both Protestant and Catholic) in which the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist was a flashpoint of sectarian violence.* I cannot understand why anyone sees anything but blasphemous horror in this. It is for this reason, above all, that I can never be an integralist, never make my peace with the history of the Inquisition,** never throw my lot in with those who want the slightest breath of state compulsion in matters of religion. Who can sincerely bring themselves to believe that the God who gave his own Son up to death for our sakes, would then have us kill our fellow men in the supposed defense of his Son? As though God could not defend his own rights if he wanted to! Anyone killed for the supposed honor of Christ has been sacrificed to Tash, and by Tash alone will that suppliant’s prayers be heard.

But enough of this hideousness. Let’s talk about fish sauce.

I’m only sort of kidding (see note i for why). Unlike last week’s epistle, most of the deeper significance in this passage comes in the textual analysis rather than the introductory background. However, we may take note of the fact that this is only miracle, aside from the Resurrection itself, recorded in all four of the Gospels.

As many people know, John shares surprisingly little content with the Synoptics. Again excepting the Resurrection (and one miracle following it†), John records only seven miracles: the changing of water to wine at Cana (ch. 2); the healing of an official’s son (ch.4); the healing of a paralytic (ch. 5); the feeding of the five thousand and the walking on the sea (both in ch. 6, in immediate succession); the healing of a man born blind (ch. 9); and the resurrection of Lazarus (ch. 11).† The second of these may be the same as the healing of the centurion’s son, recorded in Matthew and Luke, while Matthew and Mark both have accounts of the walking on water. The first, third, sixth, and seventh are uniquely Johannine, as is the ninth-or-maybe-tenth† miracle that’s performed post-Resurrection, so the selection of miracles John 6 does contain is striking. (And, just as we skipped one of my favorite bits of Mark, we’re also set to skip John 6.16-23, which features the walking on water! In the name of brevity and timeliness, I don’t plan on adding it to my posts, though I will note here that it adds something to this very story; see note q for details.)

John 6.1-15, RSV-CE

After this Jesus went to the other side of the Sea of Galilee, which is the Sea of Tiberias.a And a multitude followed him, because they saw the signs which he did on those who were diseased.b Jesus went up into the hills,c and there sat down with his disciples. Now the Passover,d the feast of the Jews, was at hand. Lifting up his eyes, then, and seeing that a multitude was coming to him, Jesus said to Philip, “How are we to buy bread,e so that these people may eat?” This he said to test him, for he himself knew what he would do. Philip answered him, “Two hundred denariif would not buy enough bread for each of them to get a little.” One of his disciples, Andrew, Simon Peter’s brother, said to him, “There is a lad here who has five barley loavese and two fish; but what are they among so many?”g-j Jesus said, “Make the people sit down.” Now there was much grass in the place; so the men sat down, in number about five thousand.k Jesus then took the loaves, and when he had given thanks,l he distributed them to those who were seated; so also the fish, as much as they wanted.m And when they had eaten their fill, he told his disciples, “Gather up the fragments left over, that nothing may be lost.” So they gathered them up and filledn twelve baskets with fragments from the five barley loaves, left by those who had eaten. When the people saw the signo which he had done, they said, “This is indeed the prophet who is to come into the world!”

Perceiving then that they were about to come and take him by force to make him king,p Jesus withdrew again to the hillsq by himself.

John 6.1-15, my translation

After these things, Jesus went across the Sea of the Galilee, or of Tiberias.a A crowd of many followed him, because they saw the signs he was doing for the infirm.b Jesus went up onto a mountain,c and there he sat beside his students. It was nearly Pesach,a the feast of the Jews.

An unleavened flatbread of the type common in

the Eastern Mediterranean. Photo by Jonathunder,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Then Jesus raised his eyes and, seeing that a crowd of many people was coming to him, he says to Philip: “Where will we buy breade so that these people may eat?” He said this, trying him, but he knew already what he was about to do. Philip answered him: “Two hundred dinars’f worth of bread would not suffice for each of them to take a little.” And one of his students, Andrew (Simon Rocky’s brother), says, “There is a little boy here who has five barley loavese and two fish; but what is that to so many people?”g-j

Jesus said: “Make the people sit down.” There was a lot of grass in that place. So the men sat down, five thousandk in number. Then Jesus took the bread and, having given thanks,l he gave it out to those sitting there; likewise also the fish—as much as they wanted.m And when they were full, he tells his students: “Gather the leftover fragments, so that nothing is lost.” So they gathered them, and stuffedn twelve baskets with fragments that were left over from the five barley loaves by those who had eaten. Then the people, seeing this signo he had done, began saying that “This truly is the Prophet is coming into the world.”

Then Jesus, knowing that they were about to come and seize him in order to make him king,p withdrew further up the mountainq by himself.

Textual Notes

a. Tiberias: It had only been founded a little over a decade before during Jesus’ ministry, but Tiberias (named for the regnant emperor, Tiberius) became a fairly important city as Jewish history proceeded. Especially after many other Jewish centers—like, conspicuously, Jerusalem—were devastated during the Jewish Wars of 66-136, Tiberias (along with places like Safed and Hebron) remained a significant Jewish settlement in the Holy Land. The Palestinian edition of the Talmud, though normally called the Jerusalem Talmud, was in fact compiled in Tiberias.

Remains of the southern gate of Byzantine-era

Tiberias. Photo by Hanay, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

b. those who were diseased/the infirm: Infirm struck me as a better translation of the Greek, both because it is a little more general than “diseased”—and, as we know, disabilities like blindness, deafness, and paralysis, though not necessarily “diseases” exactly, were also among his cures—and because it’s slightly more literal: the word here, ἀσθενούντοι [asthenountoi], is the negation of a word for strength, σθένος [sthenos], made the same way we make “amoral” out of “moral” (and indeed, we get our negating prefix a-/an- straight from Greek).

c. went up into the hills/went up onto a mountain: The RSV’s decision to render the singular as a plural here strikes me as slightly odd, but only slightly; I really only mention it here because it informs the difference in note p below.

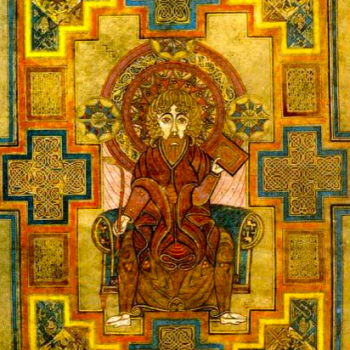

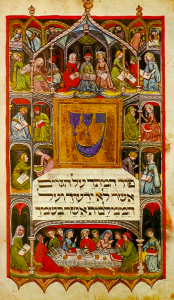

A fifteenth-century illuminated Haggadah

(book for the Passover seder) from

Heidelberg, Germany.

d. Passover/Pesach: The term in the text is Πάσχα [Pascha], borrowed from the Aramaic פַּסְחָא [Pas’châ’], itself derived from the Hebrew פֶּסַח [Pesach]. Here, as elsewhere, I’ve tried to represent linguistic distinctions present in the text (instead of leveling them, as most translations do) by turning Greek into English and non-Greek into non-English. In this case I have changed Aramaic to Hebrew because, while “Pascha” is used in some modern languages as the name for Easter (and the words Pasch and paschal did make it into English), what’s called for is a word that sounds specifically Judaic.

e. bread … loaves: This is one of the many occasions about which I’m forced to say This translation inconsistency feels incredibly silly and yet I can’t seem to find a way around it. Throughout this text, the words “bread” and “loaves” invariably represent the single Greek term ἄρτος [artos]. The trouble is, similar to rice or sugar, we think of bread not so much as an object but as a stuff; accordingly, we don’t say “breads” in English, except to talk about different kinds of bread. But ἄρτος works the other way—ἄρτος without qualification can be bread-as-substance, but one can also speak of an ἄρτος, “a bread,” which is a piece or loaf of bread (though even “loaf” isn’t quite right, as these would be more like a flatbread or naan than Western bread).

f. denarii/dinars: The modern dinar takes its name from the Latin denarius. Its various forms remain currency in Algeria, Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Tunisia, and were such until fairly recently in Bosnia, Croatia, Iran, Sudan, and Yemen.

g-j. There is a lad here who has five barley loaves and two fish; but what are they among so many?/There is a little boy here who has five barley loaves and two fish; but what is that to so many people?: Weirdly, there’s a lot going on in this sentence! The information is sort of clustered together, hence my unusual notation; let’s go point by point.

g. lad/little boy: “Lad” strikes me as oddly archaic, even a little goofy-sounding, but maybe that’s just me. However, I will defend “little boy” on strictly linguistic grounds: the word being translated is παιδάριον [paidarion], which is just παῖς [pais], “boy,” with a diminutive suffix stuck on it.

h. barley: This is one of a number of little details that often goes unnoticed in the Gospels, but contains a wealth of nuance. Barley is a coarse grain, the kind of thing that at this period was eaten chiefly by the poor; the rich preferred wheat bread.

Now, a well-known “demythologized” interpretation of the feeding of the five thousand is that it was really a “miracle of sharing,” where people were inspired by the little boy’s generosity to pass around what they had. This is, first of all, a criminally lame interpretation of a text that you can’t really excise miracles from anyway. You can decide the text is a lie, certainly; but if it is, then it’s a lie with very little truth mixed in—it’s not the sort of thing you can meaningfully “demythologize.” The miracles are too thoroughly interwoven in the whole story, from start to finish and from central point to nested footnotes.

But, aside from being lame, it’s a bit of a stretch textually. The fact that these were barley loaves (and also, hilariously, the word used for “fish,” of which more in a moment) quietly accent the fact that these (indistinct mumble)-thousand people are poor. A lot of them didn’t have a packed lunch to bring in the first place; and as we know from Mark’s lead-in to the miracle that we heard back on the 21st, this was an impromptu assembly, so a lot of those that did have a packed lunch didn’t bring it. (To those who may be scratching their heads about the indistinct mumble, when the “feeding of the five thousand” seems pretty definite, note k is for you.)

i. fish: This part is honestly a little bit funny to me. You may know that ἰχθύς [ichthüs] is the ancient Greek word for fish (or rather, one of several), but that’s not the word here. What we have here is a pair of ὀψάρια [opsaria], which is not a species of fish, but another diminutive. The term is derived from a word meaning something like “relish,” which here refers not to pickle relish, but relishes or garnishes in general: ancient fish sauce, referred to as garum by the Romans, is an important example. (A few modern condiments are possible relatives or descendants of garum or of certain types of it—including, of all things, Worcestershire sauce.) The fact that “two” are specified, and that little fish of the sardine or anchovy type were a commonplace “relish,” does point to fish, but we’re not talking about the kind of fish that are going to fill anybody up.

Ruins of a garum factory in southern Spain

(the Roman province of Hispania was a major

source of garum). Photo by Anual, used

under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

j. what are they among so many/what is that to so many people: Okay, this one actually breaks my heart a little bit, almost to the point of making me not like St. Andrew any more (but only almost). Because think it out. Why would he know this? It’s possible he caught it out of the corner of his eye, and didn’t actually interact with the kid up to that point; but if so, mentioning it sounds super weird, like they’re going to commandeer this kid’s Goldfish crackers. The only plausible explanation I’ve been able to think of—and you know what, sure, “miracle-of-sharing” people, I’ll award you half a point for this—is, this little boy overheard what Jesus and the apostles were talking about, tugged on St. Andrew’s sleeve, and offered to give them his food to help; and then St. Andrew, like a big jerk, says that, and it sure sounds like the little boy is still standing right there!

On the other hand, this would be the mother of all vindication experiences. So maybe the kid didn’t take it too hard when all was said and done.

k. men … five thousand: “Feeding of the five thousand” is arguably something of a misnomer? Greek has two words typically translated “man,” ἄνθρωπος [anthrōpos] and ἀνήρ [anēr]: the first one means “man” in the human as opposed to animal sense, synonymous with “person”; the second means “man” in the male as opposed to female sense, and is also the normal word for “husband.” When the text says that “five thousand men sat down,” it’s using ἀνήρ. Presumably there would have been more adult males than either women or children of either sex, if only because (as today) men could go places with others but could also travel alone a lot more safely than women or children, meaning that any given woman or child probably had a “chaperone” but any given man might be by himself. This doesn’t mean the men would have been a huge majority by any means; husband-wife pairs in particular might travel with a child apiece, or occasionally even with more children than that. The real numerical total of the people was presumably closer to ten thousand, though it’s hard to be sure of course. However, five thousand is the only specific number we get, and men would likely have been the most convenient to count, as they would be thought of as representing their households.

Whether the number 5,000 has any deeper significance, I can’t say. This is John, so, probably—he’s a numerology guy; when he brings up numbers, or details in general, it’s for a reason! Five thousand obviously multiplies the five loaves by a thousand, which is a little reminiscent of the parable of the sower, except that that only speaks of the seed in good soil yielding as much as a hundredfold; we therefore have a Johannine theme, stupefying superabundance, popping up (see also note m). Beyond that, I got nothing.

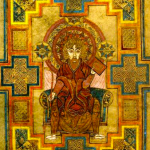

The Ardagh Chalice, an 8th-cent. Irish vessel.

Found in 1868, it is considered one of the

finest pieces of Insular art. Photo by Sailko,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

l. when he had given thanks/having given thanks: The ancient Greek verb for “to give thanks” is εὐχαριστέω [eucharisteō]. So that’s your pun for this post.

m. as much as they wanted: Speaking of both superabundance and eucharistic imagery, we have an echo here of the miracle in John 2, in which, due to how much the jars of water contained, Jesus evidently made a few hundred gallons of wine. And “as much as they wanted” is an unusually exact rendering. The several thousand people in this text were not just tided over; they were full. (John is not heavy on direct quotations from the prophets, but I can’t help wondering if some allusion to Malachi 3 was in his mind while composing this description.)

n. filled/stuffed: And yet a third time, plethora-ness comes up, as if driving the point home! This is actually sort of linked to a very funny passage in Mark, following the separate miracle of the feeding of four thousand (again counting in units of ἀνήρ, if memory serves).‡

In Mark 8, almost immediately after the second miraculous feeding, Jesus tells the disciples to be wary of “the yeast of the Pharisees and the yeast of Herod” (yeast being by then a traditional symbol of sin and subversion, thanks to its exclusion from the Feast of Unleavened Bread). The disciples think at first that they’re being reprimanded for not having the boat prepped with provisions: “It is because we have no bread.” Jesus, exasperated, reminds them of how many leftover fragments they picked up: first, after the five thousand, twelve baskets are stuffed with bread; next, after the four, seven baskets are once again filled—and this might actually mean they collected even more the second time, because a different word, σπυρίς [spüris], is used for the baskets. (This might just be natural word variation and not significant. However, a σπυρίς could big enough to fit a person inside of, which we know because a σπυρίς was what they used to sneak St. Paul out of Damascus when things got too hot for him there.) Either way, the point is that Make sure you’ve stocked bread up for us is not the point!

o. sign: Four terms in the New Testament are typically used to refer to miracles. They are:

- σημεῖον [sēmeion], “sign”—this emphasizes the meaning miracles carry, what they imply or communicate about the miracle-worker (e.g., while it is a little more complicated than this, anyone who does miracles seems to be thereby validated as God’s messenger)

- τέρας [teras], “wonder” or “portent”—this emphasizes the shock that naturally follows on the rarity of miracles; in other contexts, the same word can mean “omen” or even “monster”!

- δύναμις [dünamis], “[act of] power”—fairly self-explanatory

- ἔργον [ergon], “work”—the least common, likely because any “thing done” could be an ἔργον

John calls miracles σημεῖα, signs, almost exclusively. Perhaps not coincidentally, John is also the only Gospel with anything positive to say about faith that is, in some sense, inspired by or based on miracles: taking up the “trial” language that the author introduces as early as 1.7 (which promptly ramps up in the cross-examination of 1.19-27, and again in the thematically repositioned cleansing of the Temple in 2.14-21), the miracles are present as “evidence for the defense,” as it were.

Gold diadem, of Greek (probably Ptolemaic) make,

from the 2nd cent. BC; diadems were the

antecedents to crowns. Photo by Wolfgang Sauber,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

p. about to come and take him by force to make him king/about to come and seize him in order to make him king: I hadn’t thought of it before going through the text this time, but—especially when reading this text in a Eucharistic light—there is a pronounced irony here. On this occasion, just before Passover, he feeds people with miraculous bread, and they plan to seize him with violence and make him a king; and when Holy Week comes, just before the Passover, he feeds the Twelve with miraculous bread, and people again plot to seize him with violence, so that he is proclaimed a king. (An additional minor amusement here is that the verb translated “take by force” or “seize” is ἁρπάζω [harpazō], the root from which the name of the classical monsters called harpies—”snatchers”—is also derived.)

q. withdrew again to the hills/withdrew further up the mountain: As I mentioned above in note c, “hills” in the plural is a possible translation, even though the Greek has a formally singular noun. (I don’t know why every language seems to have certain sorts of weird grammatical features—singular forms for plurals and plural forms for singulars seem extra common, though.) It does also kind of make sense, even though it isn’t specified in the text, that they might have gone back down where the ground was more level for the feeding. That said, it isn’t specified in the text, and distributing food on a hillside isn’t necessarily that much harder; similarly, it is possible that the singular is used because a singular mountain is meant. (The adverb here, πάλιν [palin], isn’t especially helpful: it can mean “further” in a spatial sense or “again” in a temporal sense, or “again/re-” in a more abstract sense; point is, it’s nailing nothing down.) Of course, a withdrawal “again to the hills,” being a little vaguer, makes slightly better sense out of the image of Jesus somehow “shaking off” his pursuers on this occasion, when contrasted with a withdrawal “further up the mountain,” which would narrow one’s options considerably and might make one more conspicuous.

All the same, look again at the parallel just described in note p. Even if the RSV’s translation here is the better, there is a poetic propriety in phrasing this description so that the king now goes further up a mountain and is not followed by the masses, though shortly thereafter he does rejoin his disciples, who are momentarily terrified by what they think is a ghost.

Footnotes

*Ironically again, this means that even though Luther is the recognized father of Protestantism, in those regions where Luther’s doctrine of the Sacrament prevailed (since, whatever its technical problems, it is certainly a doctrine of the Real Presence), bloodshed about the meaning of the Eucharist may have been relatively slight.

**It is, sensu stricto, true that the torments and killings attributed to the Inquisition were the result not of Church policy directly, but of civil laws forbidding and punishing heresy. Inquisitors examined, and attempted to convert, those accused of straying from Christian orthodoxy; an obstinate heretic was to be, in Medieval language, “handed over to the secular arm.” He would never be punished by the clergy themselves: they could take no part of acts of bloodshed—not even hunting. Of course, the existence of civil laws punishing heresy was something the Church had never raised any serious or effective objection to. Moreover, it is surely only natural that her theoretical condemnation of converting pagans by force, like her on-paper insistence that the civil and religious rights of the Jews must be protected, were not always duly observed by Catholic states. And if any partisan of the Inquisition, past or present, sincerely thinks they can face the righteous Lord on the Day of Judgment, he who “looks on the heart” and “willeth not the death of a sinner,” with those pathetic excuses as their defense? I suppose I can’t prevent them. (I’m almost shocked that, for once in the history of popular gross misunderstandings of history, that about the Inquisition has nevertheless placed the bulk of the guilt squarely where it belongs.)

†Following the Resurrection as the eighth—which, falling beyond the seven that inevitably recalls the week and therefore the structure of time as we know it, implicitly symbolizes an entry into eternity—the miraculous catch of fish in ch. 21 would be the ninth. If one wished, one could possibly interpret Christ’s knowledge of the Samaritan woman (ch. 4) as a tenth, ten being the number of the Decalogue and also widely considered a number symbolizing mankind or completeness (thanks to our ten fingers).

‡I used to wonder if here actually might be some garbling or embroidering of the truth between these two miracles. However, the order of the miracles—the five thousand first, then the four thousand—is dead against this, as is the lesson adduced from them in Mark 8 (which not only alludes to both miracles, but does so in the order they were performed in according to both Gospels). Even the stupidest storyteller would know to put the more impressive miracle second; and the more we multiply theoretical amanuenses and textual redactors who are ostensibly willing to fiddle with the documents, the more it beggars belief that none of them corrected the anticlimactic order of these miracles; unless, of course, they were listed in that order because they happened in that order.