This post deals with the epistle and Gospel for the Eighth Sunday after Trinity (a.k.a. the Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time), as celebrated on 21 July, 2024 (Year B, week 16).

This past Sunday’s Gospel called for very few notes. By contrast, commentary on the epistle turned out to be a doozy! Not in itself, but its background. That also gave me one of my favorite things—namely, a pretext to talk about ecclesiastical architecture—so I went HAM (hence its lateness). This is your only warning. But you can skip down to the heading “Laying the Table,” if you can’t face seeing words like aperture and Latinized at whatever time of day or night you’re reading this.

How to Complain About Ritual Like a Pro

The background to this week’s epistle—the thing that makes it “pop,” if you will (and I will)—is architectural. Or rather, it’s a point that’s easy to express by means of architecture.

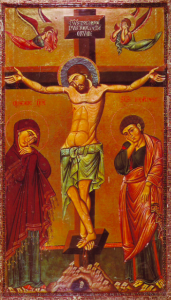

A rood atop its screen, located at the Church

of the Good Shepherd in Rosemont, PA (a

prominent Anglo-Catholic parish). Photo by

Francis Helminski: CC BY-SA 4.0 (source).

In Latin Catholic1 churches, there are a few standard elements of the architectural plan. Two are present in every church. One is the nave, which is the bit with pews in; the other, the chancel, contains the altar and ambo, or “pulpit” in Protestantese. (I’m told we don’t use that word in Catholish, even though I’ve never heard anybody refrain from using it or not understand it when it is used, but that’s not what we’re here about.) The term “chancel” is from cancellus, meaning a grille or grate: for centuries, the chancel in Latinate churches was divided from the nave by a latticework barrier, known as a chancel screen or, more often, a rood screen—a rood being a particular type of crucifix, one flanked by images of St. John and the Mother of God, that was normally situated over the central gate or doorway in the screen. In an ordinary parish church, something in the ten-to-twelve foot range would be my guess for the height of its rood screen. Or rather, that would have been my guess, if rood screens hadn’t been more or less eliminated—and here we enter upon the liturgical grumbling. Which is a competition, and a competition that I have won.

Beginners in the fine art of complaining about the liturgy occasionally try to object to the 2010 English translation of the Mass, even though it’s better in literally every way. Persons who consider themselves proficient in this art moan about the liturgical havoc wrought by the Second Vatican Council, or become sedevacantists, or attend the Extraordinary Form. To these I say: child’s play, the lot of them. For the true connoisseur of whines, there can be only one kvetch worth kvetching, and I do here kvetch it: I’m so sick of the way the Council of Trent modernized the liturgy—practically ran a bulldozer through the sense of reverence proper to the Mass. Nowadays you’re lucky to get a communion rail two or three feet high.

The rood screen of St. Helen‘s in Ranworth,

Norfolk; note the low termination of the barrier

toward the altar and its large apertures to see the

Mass. Photo by “Maria”: CC BY-SA 3.0 (source).

To be more accurate and more fair, the Council of Trent did not do away with rood screens, just as Vatican II did not abolish the use of Latin. But, as with Vatican II, many sixteenth-century scholars and clergy interpreted the provisions made at Trent as a command to excise rood screens from Christian architecture. This was based on the idea that they obstructed the participation of the faithful in the liturgy—which doesn’t even make sense, because rood screens are always pierced by doorways and apertures, for the express purpose of allowing people to see the ritual. Though mostly unaffected by Trent, the British Isles also saw many rood screens destroyed, or at least whitewashed, during the iconoclasms that accompanied the Protestant Reformation. However, architects like Christopher Wren and Augustus Pugin frequently used them in their designs, so that rood screens are now more associated with Anglicanism than Catholicism.

The very existence of this barrier is a theological statement, and one that, in my opinion, we would do well to restore. (It bears saying that even if my opinion is correct, I’m generalizing. There are doubtless churches where more would be lost than gained by adding a rood screen. But my hunch is that this would be the exception, not the rule.) The reasons why lie in the symbolism of the Temple, so let’s talk about that.

The Set Apart

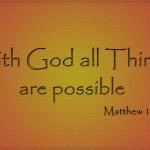

A 19th-century interpretation of the gems on the

high priest’s breastplate. This has ruby, chryso-

prase, kyanite, “tarshish,” topaz, sapphire, agate,

onyx, carbuncle, diamond, amethyst, and jasper.2

If there is one thing the Hebrew Bible is about, it is that the whole identity and purpose of the Jewish people is to serve their God. He made all the nations; and all sin by worshiping “gods” of our own devising. But he chose the children of Israel, separating them from among the nations he made, to make them his “peculiar people” (in senses 1, 3, and 4), set apart as a nation of priests for the earth, as the Levites were a tribe of priests for Israel. Everything in the Torah is devoted, directly or indirectly, to fixing this concept in the reader’s mind. Some laws, like not wearing blended fabrics, seem to have no further purpose than to say, Look: a distinction. These matter. This distinction has been elevated to a law, as a symbol of them mattering.

That setting-apart is key to the Abrahamic conception of deity. It is intimately connected both with the opening lines of the creeds that identify him as the uncreated Creator of all things—unimaginably other, at the most basic level of being possible—and with the severity of the prohibition against idolatry. We are made in his image, and therefore we are not to remake him in ours. Making idols represents a total misunderstanding of what God is. God is not a grand projection of ourselves or our likings; he is not to be toyed with, he is real. And his otherness—self-existence, absoluteness, infinity; it’s (naturally!) hard to put this into words. The core idea here is something like: We are conditioned by many things outside our control, but he is conditioned by nothing outside himself. He is the condition all others depend on.

One of the easiest ways to convey the importance of difference is with a building. This is thanks to a feature that survives in modern architecture, yet goes all the way back to pre-classical antiquity. This device is known, in the jargon of the field, as “walls.”

The Pattern of the Glory

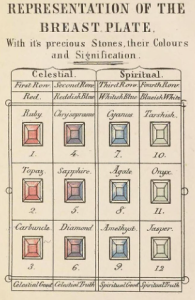

You may be able to see where I’m going with this, but I’m not done yakking about it. Hebrews reflects a common motif in Merkavah mysticism when it describes heaven as containing, or maybe being, the celestial archetype of the Temple; the Temple on earth is only its image. This is why it was so important to make everything in it “exactly as it was shown to you on the mountain.” Below is the floor plan of Herod the Great’s renovation of the Second Temple, as conceived by the artist from the 1909 Dictionary of the Bible:

This shows six barriers, six vivid settings-apart. (Five are shown in full, while the sixth and outermost, Solomon’s Porch, is partially visible.) Ritually, all Jerusalem or even all Canaan could be divided into seven parts3:

- The Holy City/the Holy Land in general

- The Court of the Gentiles

- The Court of the Women (labeled A in the diagram)

- The Court of the Israelites (C)

- The Court of the Priests (E)

- The Holy Place (F)

- The Holy of Holies (G)

Herod had the top of the Temple Mount artificially smoothed out into a large platform, and the whole sacred precinct was enclosed by a colonnade. Passing through this, one entered the Court of the Gentiles—it was this part of the Temple that Jesus cleansed, since it was occupied by a large bazaar where currency was exchanged (mainly in order to pay the Temple tax, for which Tyrian shekels were required) and animals pre-approved for sacrifice were sold.

Within this stood an inner encircling wall, pierced by gates; passing through one of these, one reached the Court of the Women, where only ritually clean Jews were allowed. On the western side of this court, a series of semicircular steps led up to another gate, within which lay the Court of the Israelites, where only ritually clean male Jews could come. Here stood the principal sacrificial altar, in front of the building we tend to think of when we hear “the Temple”—the extra-tall one in this picture:

Part of the Holyland Model of Jerusalem at the

Israel Museum. Photo by Ariely, used under a CC

BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Within was the Court of the Priests; westward again, beyond a curtain, was the Holy Place—to give it its Latinized name, the Sanctuary. This was where the Menorah, the Table of Showbread, and the Altar of Incense stood. At the back of this space hung the פָּרְוֹכֶת [par’okheth], the Veil of the Temple. This was a truly massive pair of embroidered linen curtains, dyed with the legendary Mediterranean dyes of tekhelet blue, Tyrian purple (normally more “wine-color” than what we call “purple”), and scarlet (from a source similar to modern cochineal). The embroidery depicted cherubim, emblems of the presence of God, familiar from the early chapters of the Torah and from the vision of the divine throne in Ezekiel; along with the sculpted cherubim on the top of the Ark of the Covenant—and, if they count, the almond blossoms of the Menorah and the pomegranates the high priest’s vestments—these are the only images the Torah permitted, or rather commanded, for use in Judaic worship.

Extra Credit: How Gigantic Was the Veil?

Herod’s Temple was about sixty feet high and thirty feet wide. In consequence, the Veil can hardly have been much less than fifty feet high, and couldn’t be any narrower than thirty-five or forty feet (since one generally doesn’t pull curtains taut, but allows them to almost double on themselves). This gives us a very conservative estimate of each curtain being 1,750 square feet.

What about the weight? We know they were made of linen; modern fine line weighs around a third of a pound per square foot (according to the infallible internet), so we’ll use that to base our estimate on. The Jewish historian and priest Josephus, who presumably knew what he was talking about, tells us the Veil was approximately four inches thick. Let’s pretend that modern fine linen is an eighth of an inch thick (which it’s not, it’s thinner than that, but for simplicity’s sake). Let’s also pretend, again incorrectly, that we are using the Torah’s “blue, purple, and scarlet thread,” but aren’t incorporating thread-of-gold, which would add massively to the weight. We’re also going to ignore the embroidered cherubim and any thread-of-gold they had, which would again contribute an enormous amount of weight.

If I’ve done the math right (which is a big if, but consider this: shut up), then each of the two parts of the Veil, without any of the gold or embroidery, would have weighed considerably more than nine tons. Taking averages, that’s around an elephant and a half.

In modern Judaism, a פָּרְוֹכֶת is a small curtain

behind which the synagogue’s Torah scroll is

kept; the crown stitched here is a common device.

Photo by Jacek Proszyk (CC BY-SA 2.5: source).

Finally, behind the Veil, was the Holy of Holies—the place where the Ark of the Covenant used to be. Only the high priest could enter the Holy of Holies, and only on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.* The other sacred vessels (the Menorah, the Table of Showbread, the Altar of Incense, and all the apparatus of purification and sacrifice) were carried away to Rome by Titus in the year 70, but the Ark was not. It wasn’t in the Second Temple. II Maccabees tells us that Jeremiah spirited it away before the Babylonians sacked Jerusalem and razed Solomon’s Temple; its fate is unknown.

*I incorrectly stated in a prior post that the Tetragrammaton was spoken aloud only on Yom Kippur and within the Holy of Holies. It was spoken only on Yom Kippur; however, this took place in the Court of the Israelites, in the full hearing of the assembly, who prostrated themselves when it was pronounced. Details can be found in Yoma’, the fifth tractate of the Mishnah.

The Ripping of the Veil

We will be returning to the topic of the Ark in a few weeks. As for the Veil, according to the Synoptic Gospels (Matt. 27.51, Mark 15.38, and Luke 23.45), it was ripped in half at the same moment Jesus’ soul was ripped from his body. Not only that, it was ripped “from top to bottom,” which—if nothing else had!—suggests the hand of God at work.

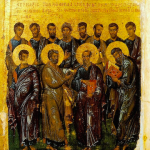

Thirteenth-century ikon of the Crucifixion from

St. Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai.

Especially when taken together with Jesus’ allusion to his body as “this temple” (John 2.19), this suggests that—to express it in mythical language—Jesus was the Temple. From the perspective of this mythical outlook, the Passion rapidly becomes intuitive. Of course he had to be “pierced” in order to act as our Mediator; without that, nothing would, literally, “go through” him. The breach of his body is our access to the Father.

All of this is why a barrier that is present, and yet punctured, is all but invaluable as a symbolic element in a church. And the rood screen is perfect for this purpose: a wall filled with windows, a barrier that lets everything through. We have crucifixes of course, and they are theologically related, but they say something different to the imagination (especially with a dozen centuries of devotional focus on the suffering they represent). And the mere absence of a barrier doesn’t say the same thing at all. Call it human silliness if you like. But the Blessed Sacrament coming from one part of the room called the chancel over to another part of the room called the nave—imaginatively, that is completely unlike the Blessed Sacrament coming from the chancel and passing through a door to us in the nave. It is of the essence of Christianity that the holy God descends to us, but equally, it is of the essence of Christianity that the holy God descends to us.

Laying the Table

I mentioned that, since Mark is the shortest Gospel, we hear more from John during Year B. Beginning on 28 July, we’ll be spending five weeks in John 6, which features the miraculous feeding of the five thousand and the “I Am the Bread of Life” discourse. The same miracle does immediately follow in Mark; I gather the Lectionary has been so arranged as to allow John’s account to be slipped in at the same point as Mark. (I think this must be why one of my favorite bits of Mark—the exorcism of the man possessed by Legion—got axed, as I lamented at the end of June. However, given how short the Gospel passages were both this week and the week before, if anything, I’m now even crabbier about it.)

In any case! We’ll be shifting gears again as of Sunday, through the end of August. Let’s proceed with the epistle.

Ephesians 2.13-18, RSV-CE

But now in Christa Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. For he is our peace, who has made us both one, and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility,b by abolishing in his fleshc the law of commandments and ordinances, that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us both to God in one body through the cross,d thereby bringing the hostility to an end.e, f And he came and preachedg peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near; for through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father.

Ephesians 2.13-18, my translation

As of now in Jesus the Anointed,a you who were far away have become near in the blood of the Anointed. For he is our peace, who made both one and destroyed the middle wall of the hedge,b abolished the enmity in his flesh,c the law of commands in teachings, so that he might make the two in himself to be one new person, making peace, and might transform both in one flesh to God through the cross,d killing the enmity in himself;e, f and he came and brought the good newsg of peace to you far away and of peace to those near; so that through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father.

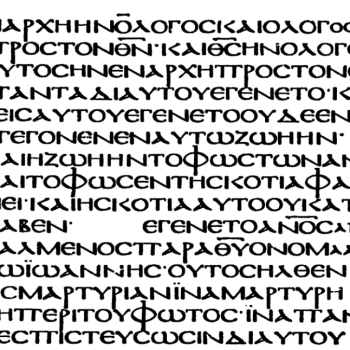

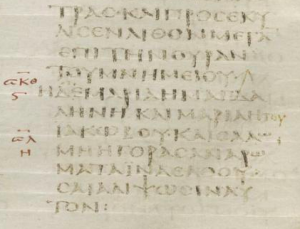

Textual Notes—Ephesians

a. Christ/the Anointed: In several ancient Semitic cultures, anointing with oil was a sign of appointment to office, especially sacred or royal offices. The title “messiah” literally means “anointed one,” and the Greek translation of that title is Χριστός [Christos]; for whatever reason, this is one of those terms that did get translated across the Hebrew-Greek barrier, but not the Greek-Latin barrier. I’ve gone with the literal translation “anointed” (or, where called for by English syntax, “the anointed” or “the anointed one”). However, two alternatives did present themselves to my mind. One, I’ve reluctantly decided against; I can’t seem to make up my mind about the other.

The idea I discarded was to translate Χριστός as “Prince.” This gives a tolerably good idea of what being “the Lord’s anointed” meant, especially since heirs to the thrones of Israel and Judah were often anointed during their father’s reigns. In Europe too, during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, it was common for heirs to be crowned while their predecessors were still alive; this was a way of cementing the succession.

The drawbacks of “prince” are largely linguistic. The adjective anointed goes with the verb anoint, the noun ointment, and the gerund anointing, which can render verbs like χρίω [chriō], “to anoint,” or nouns like χρῖσμα [chrisma], “anointing, unction.” By contrast, prince doesn’t have many relatives; the only one I could think of, which is of limited usefulness, is princedom (or its Latinate synonym principality). All in all, given my stated philosophy of translation, “prince” just doesn’t make the cut.

The other option would be to keep the term Christ and adapt other parts of the translation to parallel it: for example, taking a leaf out of Eastern Christendom’s book and speaking not of “anointing” but of “chrismating” (or, though at risk of serious misreadings, of “christening”); a phrase like “anointing oil” could easily be turned into “chrism.” I’m not sure this would result in a readable text for most English speakers, but I haven’t definitely kiboshed it—especially since the idea of anointing needs a little introduction for most people anyway.

Piercing of Christ’s side, portion of a fresco by

Fra Angelico in St. Mark’s, Florence

(early fifteenth cent.)

b. dividing wall of hostility/middle wall of the hedge: For many Christians, the remotest allusion to laws and hedges or fences within the same paragraph will immediately call to mind every sermon they’ve ever heard that deals with the Pharisees: they “built a hedge about the Law,” and then judged and condemned people for breaking that, which is why Jesus rebuked them for “teaching as doctrines the traditions of men,” etc. (Interestingly, if I can judge from my own experience, only the anti-Catholic implications of such preaching are usually clear in the audience’s mind; the fact that these sermons are, explicitly, anti-Judaic4 seems almost to pass unnoticed.)

Now, this may well be what St. Paul had in mind here. The language of “fences” or “hedges” is not absent from rabbinic Judaism, and Paul was a Torah scholar; furthermore, insofar as rituals like circumcision, the sabbath, and kosher were what set God’s people apart as Jews, the fact that the New Covenant gave Gentiles equal access to God without needing to become Jews did radically alter the nature of that hedge. However, even if this is what the apostle was talking about, we need to clear something up about these “traditions of men,” a subject I have touched on before in our journey through Mark. Let’s review.

According to the Pharisees, the Written Torah (i.e. the Pentateuch) was more properly one part of the Torah. It was given, and meant to be kept, along with the Oral Torah, which added the necessary context and interpretive principles to understand and apply the Torah. Many Christians will read this and promptly think, Ah, this “Oral Torah”—all of the Pharisees’ own devising, no doubt—this must be the artificial extension of the Law that Jesus condemned them over. Like Eve in the Garden, elaborating the command! A perennial human failing. It’s a popular interpretation. And this popular interpretation comes at the low, low cost of just the Gospel of Matthew.

Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill. For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled. Whosoever therefore shall break one of these least commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven: but whosoever shall do and teach them, the same shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven. For I say unto you, That except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven.

Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

The scribes and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat: all therefore whatsoever they bid you observe, that observe and do; but do ye not after their works: for they say, and do not. (Matt. 5.17-20 22.37-40, 23.2-3)

A reproduction of the Temple Menorah (which was

most likely the basis for the “seven lampstands”

of the first three chapters of Revelation) created

by the Temple Institute.

In my opinion, it’s the third and shortest reference here that’s the most disastrous to any “the Oral Torah was made up” interpretation. I don’t know whether even the Pharisees themselves claimed to “sit in Moses’ seat”; maybe they did; if so, then on a Christian showing, that claim was validated by God made flesh. If they didn’t, then Jesus’ words here are still more shocking, for they elevate the Pharisees beyond their own belief in their own authority.

And we haven’t even begun to discuss the fact that, while Jesus’ doctrine and halakhah5 (especially about the sabbath), and of course his messianic claims, did clash with the doctrines of other Pharisees, this was a clash with other Pharisees. He was a Pharisee, theologically. On every doctrinal dispute between the Pharisees and other sects of Judaism, Jesus was on the Pharisees’ side: whether it was the resurrection of the dead and the reality of angels and human souls (against the Sadducees), or the unique validity of the Temple in Jerusalem (against the Samaritans), or the ongoing validity of that Temple (against the Essenes6), or in refraining from violence and leaving the restoration of Jewish autonomy to the timing of God (against the Zealots)—on all of these questions, Jesus gives the Pharisaic answer. And there in Matthew 23, right before declaring the Seven Woes against the Pharisees, he makes it crystal clear that he is condemning their behavior and their outlook, not rejecting their authority or telling others to do so. This was so clear at the time, despite the heterodoxy of the Nazarene movement, that, as much as twenty-odd years after the Crucifixion, Paul was still able to leverage it as a maneuver in his own trial.

A portrait of Moses in a stained-glass window in

the Temple De Hirsch Sinai, a Reform

synagogue in Washington state.

But if Jesus wasn’t condemning the Oral Torah, then what was his beef with the “traditions of men”? Well, hang on. There’s Oral Torah and there’s Oral Torah. The commandments which fell under it came from different sources; not all of them had, or were ever claimed to have, equal authority, any more than every Catholic small-t tradition is held to have the doctrinal or moral status of Tradition. (For example, after Vatican II, we saw the relaxation of Friday abstinence, which was a very ancient custom but was never held to be more than a simple custom, except by the ignorant; conversely, the Tradition that the Mother of God had been assumed bodily into heaven was codified as dogma not long before Vatican II.)

For our purposes, the Oral Torah can be grossly oversimplified as falling into two categories: divine traditions handed down through Moses and the prophets on the one hand, and on the other, customs and halakhic rulings established later, mostly by scholars. Only the first would be fully authoritative. The second would be open to critique, at least under some circumstances. And the circumstance the Gospels present, lo and behold, is that “something greater than the Temple is here.”

c. flesh: There’s an interesting distinction here, one that exists in both Greek and English but, to my knowledge, is not common outside of Christian (or at least Christian-influenced) thought. The distinction is between σάρξ [sarx], “meat” or “flesh,” and σῶμα [sōma], “body.” The usage of these terms is not absolutely consistent across the New Testament. In the writings of Paul, σάρξ often denotes our instinctively selfish and corruptible part, while σῶμα refers to the body, neutrally; by contrast, in the Johannine books, σάρξ is a neutral if not positive term, as in John 1.14 where we are told that “the Logos became σάρξ and dwelt among us”.

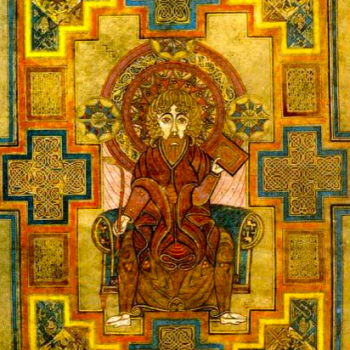

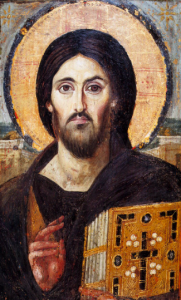

Ikon of Christ Pantokrator from St. Catherine’s

Monastery on Mount Sinai. It is the oldest known

ikon of Jesus; the contrasting halves of his face

are held to represent his deity and humanity.

This discrepancy in New Testament usage is natural, especially since not all the authors of the New Testament were native speakers of Greek.7 Moreover, the only thing approximating what we would now call an ecumenical council (the synod held at Jerusalem around the year 49, described in Acts 15) was convened to deal with an urgently practical question of Christian discipline. Unlike the First Council of Nicæa in 325, it was not so much addressed to the ideas and intent that animate discipline; it’s only disputes over ideas that can be settled by defining official terminology (like ὁμοούσιος [homoousios] was designed to do). There was no particular reason for the apostles to have spontaneously drawn up an agreement about how they were all going to use vocabulary items.

Many people have taken the negative sense of σάρξ in St. Paul to be dualistic, or even quasi-Gnostic; I doubt this, for a few reasons. One is simply that “according to the flesh” is one of his recurring phrases to describe the Incarnation and his own relationship to fellow Jews, both of which he plainly treasured! Furthermore, when it is used in “sinful nature” contexts, σάρξ is not specially associated with sins of lust or gluttony, but with sin in general and its “way,” contrasted with the “way” of the Spirit. And while the New Testament is very alive to sins against chastity and sobriety, it is, if anything, even more on watch against sins like anger, callousness, ego, avarice, envy, and hypocrisy—social and spiritual sins.

d. the cross: The word σταυρός [stauros] is normally used in Greek for crosses. However, it did not at first refer to the cross as we picture it, partly because crosses themselves changed somewhat over the course of history. Originally, a σταυρός was a stake (as in “burn at the”); being placed on one was as likely to be an impalement as a hanging. In Latin, this undeveloped vertical gibbet was eventually labeled a crux simplex (“single stake”8); the adjective simplex was introduced to distinguish it from the crux commissa and crux immissa. The former, the “joined cross,” had a cross-bar directly on top resulting in a T-shaped device. The immissa was more like the + or † shapes we are acquainted with.

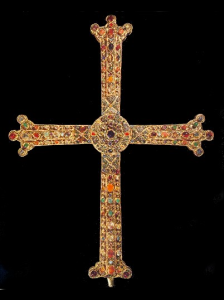

The “Victory Cross” from the Cathedral of the

Holy Savior in Oviedo, Spain. Made in 908, it

stands about three feet high, and is decorated

over a hundred real and imitation gemstones.

e. thereby bringing the hostility to an end/killing the enmity in himself: Not to sound like a broken record, but yet again, why was this not rendered more literally? It’s so much better! Am I just the crazy person, who likes it when books are good?

f. ./; : In this passage, as in other places in the Pauline corpus, the author9 presents us with what English syntax classifies as a run-on sentence, piling phrase upon phrase anyhow. English is very particular about its hierarchies of clauses and carefully-enumerated negatives and so on, in a way many languages are not; this has advantages (certain fine shades of distinction in negations are much easier to convey in English, for instance), but it can also make the more impressionistic prosody of many languages tricky to convey.

g. preached/brought the good news: Say it with me: “preached isn’t inaccurate, but”. Specifically, this verb is directly related to εὐαγγέλιον [euangelion], “gospel” or “good news,” and is the origin of the English verb “evangelize.” Speaking of which.

Mark 6.30-34, RSV-CE

The apostles returned to Jesus, and told him all that they had done and taught. And he said to them, “Come away by yourselves to a lonely place,g and rest a while.” For many were coming and going, and they had no leisure even to eat. And they went away in the boat to a lonely place by themselves. Now many saw them going, and knew them, and they ran there on foot from all the towns, and got there ahead of them. As he landed he saw a great throng, and he had compassion on them,h because they were like sheep without a shepherd; and he began to teach them many things.

Mark 6.30-34, my translation

And the emissaries came together to Jesus, and they reported everything which they had done and taught. And he tells them: “You come by yourselves into a deserted placeg and stop there a little while.” For many people were coming and going along—they had no time to eat, even. And they came away in the boat to a desert place by themselves. And they saw them coming along, and many knew about about it, and they ran together on foot from all the cities there and came to them. And they saw a great crowd coming out, and his heart ached for them,h because they were like sheep that do not have a shepherd, and he began to teach them many things.

Textual Notes—Mark

g. a lonely place/a deserted place: I’ve gone with “desert” or “deserted” to translate the adjective ἐρῆμος [erēmos]. It corresponds to the later history of the word somewhat better: eremitic and hermit, used to describe wilderness monasticism and its exponents (like St. Anthony the Great), are both derived from ἐρῆμος. It is particularly well-suited to the Biblical “corner” of the Mediterranean—modern Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria—whose outlying regions are desert in the climatic sense. (“Lonely” comes from “alone,” itself from the Anglo-Saxon ᛠᛚᛚ ᚪᚾ [eall ān], “all one”; this may be less suitable, in that there is no parallel in the relevant Greek etymologies: ἐρῆμος is not related to ἕν [hen], “one.” However, the English “desert” is not related to its root in the way ἐρῆμος is related to its, so this argument doesn’t go far!)

A composite satellite image of the Levant and the

Syrian Desert; the large sea on the left is the

eastern Mediterranean.

h. he had compassion on them/his heart ached for them: The verb here, σπλαγχνίζομαι [splanchnizomai], is derived from σπλάγχνον [splanchnon], a derivative of the word for “spleen” (which, as I did not know before researching this post, plays a role in filtering the blood). Σπλάγχνον seems to have been more general, a little like guts or bowels; until a few centuries ago, it was still possible to speak in English of a person’s “bowels being moved” with some emotion, most often compassion. (In the aforesaid centuries, of course, that turn of phrase has acquired a different and, contextually speaking, unfortunate meaning.) “Heart” is thus not strictly accurate in the literal sense I usually prefer, but works perfectly as a sense-for-sense translation.

Footnotes

1The rite of a Church is the liturgical and cultural tradition it belongs to. All Catholic rites belong to one of six families: the Alexandrian, Antiochene (or West Syriac), Armenian, Byzantine (or Greek), Chaldæan (or East Syriac), and Latin; the Byzantine and Latin ritual families are especially variegated. The best-known of the Latin rites is the Roman Rite, but a small number of other Latin rites also exist, like the Ambrosian Rite of Milan. There are also uses, which are more minor variants of a rite: one example is the modestly well-known Anglican Use of the Roman Rite. (I’m not clear on the difference between a mere use and a fully-fledged rite; the only distinction I’ve detected is the spelling.)

2Ancient Hebrew gemology is not well understood, and the identity of most of the stones on the breastplate is a matter of debate—also, this particular illustration is sideways for some reason! (One source of difficulty is that in the ancient world, gems tended to be classified by appearance, not as now by chemical composition.) To the extent there is a scholarly consensus, the twelve stones in their four rows may have been as follows: 1. Carnelian, peridot (?), and onyx (?); 2. turquoise (?), lapis lazuli, and zircon (??); 3. amber, agate, and amethyst; and 4. desert glass (??), beryl (?), and jasper (??). Each of the stones on the breastplate was incised with one of the names of the Twelve Tribes, probably in the order of their birth (though this too is uncertain).

3To be clear, I’m not claiming this sevenfold division was actually used, or even proposed, back then. This is more like a mnemonic, accenting the holiness of Israel among the nations, the Temple within Israel, and the Holy of Holies inside the Temple.

4This might seem puzzling. The Pharisees were just one group, from thousands of years ago, someone might say; is it “anti-Judaic” to ever disagree with any Jews now? No. The issue is, the Pharisees are not just a random group of Jews. After the destruction of the Temple, most other Judaic sects rapidly died out, and the Pharisees became the doctrinal ancestors of almost all modern Judaism. If we want—as we should—to avoid injustice, stupidity, and discourtesy toward the Jewish people, then we must be prepared to think twice about casually denouncing the basis of most Judaic thought and practice. Conveniently, we also have good reasons from our own religion to reinforce that lesson.

5Halakhah is the rabbinic application of the Torah. A convenient example is the kosher practice of eating meat and dairy separately: to avoid “cheating,” how separate should they be kept? Different customs arose in different regions: in some, a wait of six hours between eating dairy and eating meat was standard; others made it one hour, or three. Yet these are obviously all interpretations of the same rule. This process of interpreting and applying the commandments is halakhah.

6The Essenes are perennially fashionable because they’re interestingly weird—secretive, apocalyptic, mystical, etc. A less well-known characteristic of the Essenes is that they typically rejected the Temple and its sacrificial system—something Jesus’ family and the primitive “Nazarenes” decidedly did not.

7The books of Luke and Acts are written in good Greek, as is the Pauline corpus (run-ons or no). Of the other New Testament writings, all are traditionally attributed to non-native Greek speakers; some show definite evidence of this. The Gospel of Mark and the Apocalypse, especially the latter, are written in Greek that is sometimes downright clumsy, and in a different vein, while the Gospel of John has a certain stylistic elegance, it is of a distinctly non-Greek type.

8I’ve here used “stake” to translate crux, but, unlike the Greek term, what (if anything) crux meant before it was applied to crosses is unclear.

9There is some doubt among scholars about whether Ephesians is a genuine letter of Paul. I was astonished by the arguments against its authenticity; that is, astonished at how utterly unconvincing they are: a tissue of special pleading, circular logic, and assertions balder than a billiard ball. I won’t get into it now, but I can recommend the (slightly old) book Redating the New Testament by J. A. T. Robinson on the subject. Still, I wouldn’t feel I was playing fair with my readers if I didn’t explicitly say, a large number of scholars both past and present are against me on this. They’re wrong, but they are against me. They’re zero for two, is what I’m saying.