Ambassadors

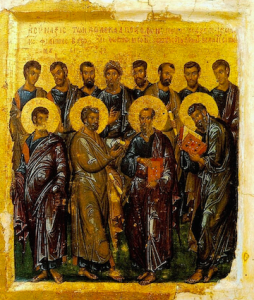

An ikon of the Twelve

I’ve laid things out a little unusually in this post. Instead of just addressing the Gospel reading, I’m analyzing it together with its parallels in other Gospels. These are all about the mission of the Twelve Apostles. This is not the Great Commission; that comes later, after the Resurrection. This is when the Twelve were sent on their first “solo project” (solo in the sense that Jesus wasn’t physically present there). It was a mode they’d need to get used to in a few years’ time—a first “off-book” rehearsal for what they’d be doing for the rest of their lives, in fact.

What is an “apostle”? It’s a religious word to us, but like I was saying in my last post, that’s because it’s “Greeklish,” and Greeklish words were all ordinary terms to the people who actually spoke Koine Greek. Taken hyper-literally, ἀπόστολος [apostolos] means “sent one”; a host of more natural synonyms comes to mind: ambassador, envoy, messenger, emissary, nuncio, legate, missionary, spokesman. There are probably more. The point is, in the world of international relations, this is familiar. It’s a common function—a common class of functions, really—that any sovereign, even of a tiny state, is going to deal with very formally and officially, to ensure first that he’s being represented correctly, and second, that the people who meet his qualified representatives are treating them right, because that’s a signal of how they view him, his crown, and his whole people.

A tabard (a bit like a chasuble) once worn

by heralds of the British crown—note the

quartered arms.1 Photo by Nicholas

Jackson (CC BY-SA 3.0 license: source).

This is, if anything, ramped up in the Near East, especially back in antiquity. It’s not uncommon for an author to make no explicit distinguish between a message sent from someone and an appearance of that person: the centurion with faith that surprises Jesus himself is a great example, given that Matthew writes about him as if he (the centurion) were there in person, whereas Luke (who’s from a Gentile background) specifies that the centurion sent elders and friends of his, bearing messages. Luke, too, records the saying, “He that heareth you heareth me; and he that despiseth you despiseth me; and he that despiseth me despiseth him that sent me.” Biblical prophets were understood in precisely these terms. This principle went further still. At least some of the Judaic wariness about the Divine Name came from an idea that a person’s name, in some sense, was the person—to injure or mis-handle someone’s name was to do them real (if invisible) harm.

As a result, ἀπόστολοι aren’t exactly ambassadors in the modern sense. Ambassadors are often appointed for short terms, do not normally designate their successors, and cannot be automatically presumed to have full powers to represent their state the way that, well, a head of state does; moreover, ambassadors (and the embassies of which they are a part) are normally only present in, or at least only open and operating in, countries that are at peace with their own. Jesus’s ἀπόστολοι are appointed to all appearances for this life and the next are capable of transmitting their office, are told several times that they possess full powers, and are not only anticipated but even assumed to be operating in actively hostile territory. It’s tempting to translate it as something like “viceroy.” I think the translation I’ve most opted for in fact has been “emissary,” since, not being a formal legal title in most of the historical reading I’ve done, it has more leeway than terms like “legate” or “ambassador.”

Remains of a temple to Pan near Cæsarea

Philippi (modern Banias); when Jesus tells

the Apostles “the gates of hell shall not prevail,”

they may have been in sight of this temple.

The textual notes are arranged a little differently in this one. Due to differences in content or completeness among the Synoptic Gospels, none of the passages below bear the complete set of notes a through I. (Mark has five: a, E, f, h, and I. Matthew has seven—B, C, D, E, G, h, and I—and Luke, four: B, E, h, and I.) Also, content in the other two Gospels that is not present in Mark is shown in green. (Since I’m only providing my personal translation for Mark, I’ve simply offered the RSV-CE’s version of the parallel Gospel passages.)

Mark 6.7-13, RSV-CE

And he called to him the twelve, and began to send them out two by two,a and gave them authority over the unclean spirits. He charged them to take nothing for their journey except a staff;E no bread, no bag, no moneyf in their belts; but to wear sandals and not put on two tunics. And he said to them, “Where you enter a house, stay there until you leave the place.h And if any place will not receive you and they refuse to hear you, when you leave, shake off the dust that is on your feet for a testimony against them.”I So they went out and preached that men should repent. And they cast out many demons, and anointed with oil many that were sick and healed them.

Mark 6.7-13, my translation

And he summoned himself the Twelve, and began to send them forth two by two,a and he gave to them authority over unclean spirits, and directed them to take nothing on the road except a single rodE—no bread, no bag, no copperf in the belt, but to tie on their sandals, and not be clothed in two cloaks. And he told them: “Wherever it may be you come into a household, stay there until you leave the place.h And if that place will not receive you nor listen to you, when you leave there, shake off the dust that is under your feet, as a witness to them.”I And they went out and proclaimed that people should have a change of heart, and cast out many demons, and anointed many sickly people with oil and healed them.

A Russian Orthodox chrismarium2 (there known

as an Алавастр [Alavastr]). Photo by Shakko,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Matthew’s Parallel (10.1-15)

And he called to him his twelve disciples and gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to heal every disease and every infirmity.B The names of the twelve apostles are these: first, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother; James the son of Zebedee, and John his brother; Philip and Bartholomew; Thomas and Matthew the tax collector; James the son of Alphaeus, and Thaddaeus; Simon the Cananaean, and Judas Iscariot, who betrayed him.C

These twelve Jesus sent out, charging them, “Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.D And preach as you go, saying, ‘The kingdom of heaven is at hand.’B Heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers, cast out demons. You received without pay, give without pay. Take no gold, nor silver, nor copper in your belts, no bag for your journey, nor two tunics, nor sandals, nor a staff;E for the laborer deserves his food.G And whatever town or village you enter, find out who is worthy in it, and stay with him until you depart.h As you enter the house, salute it. And if the house is worthy, let your peace come upon it; but if it is not worthy, let your peace return to you. And if any one will not receive you or listen to your words, shake off the dust from your feet as you leave that house or town. Truly, I say to you, it shall be more tolerable on the day of judgment for the land of Sodom and Gomorrah than for that town.”I

Luke’s Parallel (9.1-6)

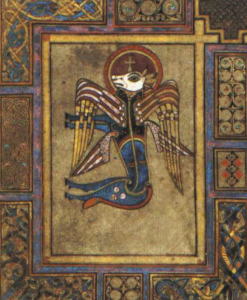

Symbol of St. Luke from folio 27 of

the Book of Kells (9th cent.)

And he called the twelve together and gave them power and authority over all demons and to cure diseases, and he sent them out to preach the kingdom of God and to heal.B And he said to them, “Take nothing for your journey, no staff,E nor bag, nor bread, nor money; and do not have two tunics. And whatever house you enter, stay there, and from there depart.h And wherever they do not receive you, when you leave that town shake off the dust from your feet as a testimony against them.”I And they departed and went through the villages, preaching the gospel and healing everywhere.

Textual Notes

Since I’ve put Mark beside Matthew and Luke, I’ve set up the notes slightly differently. Notes in capital letters (B, C, D, E, G, and I) discuss text that’s in the other two Synoptics,3 while those which are also in italics (B, C, D, and G) refer to information found only in other Synoptics; notes a, f, and h are the only Mark-exclusives. To help avoid confusion, within the references themselves, I’ve set text from Matthew in dark red and text from Luke in dark blue; text from Mark remains in black.

a. two by two: Only Mark mentions the detail that the Twelve were sent out in pairs, though he doesn’t tell us what they were. Matthew seems like he may be listing the pairs: if so, they were Peter-Andrew, “big” James-John, Philip-Bartholomew, Thomas-Matthew, “little” James-Thaddæus, and Simon-Judas. This reveals that our Lord tastefully assigned those six apostles who shared first names—the Jacobs, Judahs, and Simons4—to different teams. He also put the two confirmed sets of brothers together; however, if Matthew and James the Less were brothers (check the bullet on the name “Matthew” in note C), them he split up for some reason. Luke does mention pairs when talking about the later mission of the Seventy5 (which only he records), but not here.

B. and to heal every disease and every infirmity … And preach as you go, saying, “The kingdom of heaven is at hand.” | to cure diseases, and he sent them out to preach the kingdom of God and to heal: Curiously, while both Matthew and Luke mention express instructions to preach the gospel, Mark—though he mentions that they did preach—has nothing to say about what message they were told to bring to people. Presumably, since they had been apprenticed to Jesus for a while at this point, they had seen him preach quite regularly, and had an idea of what to say.

Similarly, though he mentions acts of healing—and specifies anointing with oil, a detail left out by the other two—Mark has nothing to say about the commission given to the Twelve to heal the sick: the only authority he mentions is that which they were given over demons. This could indicate that a somewhat superstitious way of thinking about diseases was habitual to the author of Mark or to his sources—or at least, that he/they were in the habit of speaking that way, which is not necessarily the same thing. (That said, the absence of a single clause from one passage can’t bear much theological weight!)

Calling of the Apostles (1481)

by Domenico Ghirlandajo

C. The names of the twelve apostles are these: first, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother; James the son of Zebedee, and John his brother; Philip and Bartholomew; Thomas and Matthew the tax collector; James the son of Alphaeus, and Thaddæus; Simon the Cananæan, and Judas Iscariot, who betrayed him: All three Synoptics list the Twelve; only Matthew does it here. Mark’s list is in chapter 3, where it says “he ordained twelve, that they should be with him, and that he might send them forth to preach, and to have power to heal sicknesses, and to cast out devils.” This suggests that this mission was anticipated, and maybe even discussed when the Twelve were originally selected, but that he kept them with him a while first. (It might even mean their ordination preceded their training, which would be wild by our standards.) Luke lists the apostles twice: once in his Gospel (in chapter 6, around the same position as in Mark’s shorter narrative), and again in the first chapter of Acts.

I’d like to get into some of the names and epithets here—nine, all told. We’ve touched on four of them on this site already: Alphæus, Peter, Thomas, and Zebedee.

- Alphæus probably represents the same name as Clopas/Cleophas: חילפאי—a name I can’t really transcribe properly, because I can’t find a version with the niqqud and I’m not good enough at Hebrew or Aramaic to insert any vowel except “a” when in doubt.6 But I’m assured by better-informed people that it comes out to [Chilfai].

- Peter, “Rocky,” is a well-known nickname: Πέτρος [Petros] represents the Aramaic כֵּיפָא [Keyfa’], or Cephas.

- Thomas, “Twin,” is almost certainly a nickname as well; at least, I’ve never heard of anybody actually being named “Twin.” Δίδυμος [Didümos] stands for תְּאוֹמָה [T’owmah] of the same meaning.

- Fourth, Zebedee is the same as Zebadiah (in Hebrew זְבַדְיָה [Z’vad’yah]), filtered as usual through the classical languages and then Anglicized. (Incidentally, Zebadiah means “gift of God.” No, you’re not misremembering, that’s also what Matthew means; they really just did this twice.)

Five others drew my eye: Bartholomew, Cananæan, Iscariot, Matthew, and Thaddæus.

Judas Iscariot in stained glass at the

Church of St. John the Baptist in Yeovil,

Somersetshire; note the black halo.

(GadgetSteve, CC BY-SA 4.0: source.)

- Bartholomew is a surname. The prefix “bar-” functions a little like “Mc-/Mac-” in Gaelic surnames; -tholomew, on the other hand, is the Aramaic name Talmai. This name came from Hebrew, and was also used as the Hebraization of the (quite unrelated) name Ptolemy. Based on the fact that bar-Talmai in the Synoptics is regularly paired with Philip, he is thought by most people to be the same individual as Nathanael in John—thus netting us a first and last name, Nathanael bar-Talmai.

- St. Jerome suggested that Cananæan might mean “from Cana,” which is the origin of the (very misleading!) rendering “Simon the Canaanite” you’ll occasionally find. However, the older and more common theory is that Cananæan comes from קַנַּאי [qanna’y], “zealous.” If Greek bothered to borrow an Aramaic word, it probably had some special significance: referring to a localized movement like the Zealots would do nicely. This is reinforced by Luke titling him ζηλωτής [zēlōtēs]. Granted, it’d be surprising for a Zealot to start following a pacifist rabbi; but personally, I’d be even more surprised if no Zealots changed their minds on hearing Jesus. I see no reason to doubt the old theory.

- The name Iscariot has prompted a couple theories. One is that it’s a lightly scrambled form of the Latin sicarius, which means “assassin” or “hitman,” and that Judas’s background was similar to Simon’s. There was a Zealot-aligned group of sicarii active in Judæa a little after Jesus’s time, in the 50s. However, not all Zealots were murder guys who loved to do murders; and while the Romans called them sicarii, I don’t know that that name was current among Jews. Besides, while Jesus and/or the other apostles calling one guy “Simon the Zealot” is one thing, openly referring to another as “Judah the Hitman”—before all the, you know, went down—seems a little far-fetched. And that’s to say nothing of their doing so in Latin, garbled or not. Anyway, there’s a more natural explanation: there was a town in Judæa called קְרִיּוֹת [Q’riyyowth], “Kerioth.” Prefix the Hebrew word for “man,” אִישׁ [‘iysh], to make “guy from Kerioth,” and what do you know: ish-Kerioth. But nah, sure, it’s the murder one.

A seventeenth-century Armenian miniature

of St. Matthew the Evangelist.

- Matthew is an interesting case.7 All the lists of the Twelve contain his name. The Gospel of Matthew also records him being called from the tax-collector’s office, but Mark and Luke, in relating an identical story, make it about a man named Levi. (Mark adds the tantalizing detail that Levi is a “son of Alphæus.” Like James the Less? Do we have a third set of brother-apostles?) Levi is broadly agreed to be Matthew, but I haven’t discovered an explanation for the naming discrepancy. Of course, it wasn’t uncommon for a person to have multiple names, but there’s normally a reason—from one as simple as “he also has a nickname,” to elevated causes like a religious initiations. I wonder whether Mark and Luke, knowing what a bad figure tax-collectors cut, were sensitive to what people might think of Matthew and so quietly omitted the fact that he was Levi; but, perhaps St. Matthew couldn’t be bothered to stand on his dignity. That would align with St. Paul’s attitude, and we see what may be echoes of Matthew in Paul’s writings (cf. note G). Of course, this rests on the assumption that the Synoptics, or Matthew at least, were written by the saints they’re named for, an idea not widely accepted by scholars. (I find the arguments against the tradition unsatisfying, but it is true that I’ve got most of Academe against me on this.)

- Finally, Thaddæus, thought to be the same as John 14.22’s “Judas saith unto him, not Iscariot” (nice save). The etymology of Thaddæus is uncertain, but some of what I read proposed it was a version of the Aramaic תַדַּי [Thadday], which appears to come from תַּדָּא [tadda’], “breast.” The name thus could mean something like “suckling child.” The image that immediately came to me—and which, to be honest, strikes me as credible, if not inevitable, in a group of thirteen men hanging out for months on end—is that one guy in the group basically got the same nickname as “Baby John” from West Side Story.

A lunette with fifteen relics of apostles:

the Eleven are all here, as are SS. Matthias

Barnabas, and Paul, plus two from St. John.

(By ExorcisioTe, CC BY-SA 4.0: source).

Taking the Evangelists’ four lists and combining it with data gleaned from John, we get a probable list8 of “The Twelve Classic” along these lines:

- Simon “Rocky” bar-Jonah | St. Peter

- Andreas bar-Jonah | St. Andrew

- Jacob bar-Zebadiah | St. James the Greater

- John bar-Zebadiah | St. John

- Philip | St. Philip

- Nathanael bar-Talmai | St. Bartholomew

- Levi “Matthias” bar-Chilphai | St. Matthew

- “the Twin” | St. Thomas

- Jacob bar-Chilphai | St. James the Less

- Simon “the Zealot” | St. Simon

- Judah “Baby Jude” bar-Jacob | St. Jude Thaddæus

- Judah “of Kerioth” bar-Simon | Judas Iscariot

Contemporary Samaritans observing Passover on

Mount Gerizim, 2006. Photo by Edward Kaprov,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

D. Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel: Characteristically, Matthew focuses on the explicitly and at this stage exclusively Jewish mission of Jesus and the Apostles. Mark rarely if ever touches on this (he has nothing to say about the dispute between orthodox Jews and Samaritans, for instance, a topic even John takes head on); St. Luke, a Gentile convert and close associate of St. Paul, downplays it.

E. except a staff/except a single rod | nor a staff | no staff: This is an odd discrepancy between Mark and the other Synoptics. The best I can make of Mark’s phrasing is that the word μόνον [monon], which I think the RSV is taking to mean “only” (in the sense that it is the “only” exception to Jesus’s directions to under-prep), is really being used in a numerical sense here. In other words, they’re allowed to bring a staff, but only one—no backup: if it breaks, it breaks, and they’ll have to either do without a staff or accept a new one as a gift.

f. money/copper: Then as now, money was 1) often made from copper or copper alloys, but 2) usually only for the smallest, least valuable coins, like pennies.9 Idiomatically, “don’t bring a penny” would be a very defensible rendering.

An ancient lepton, the “mite” of the widow’s

mite episode, sometimes translated “penny”;

it was typically made of copper and might

be referred to simply as “a copper.”

G. the laborer deserves his food: St. Paul alludes to this idea a few times (e.g. in I Corinthians 9), and in I Timothy 5 he quotes it directly.

h. stay there until you leave the place: The command not to go from house to house in a single city or town could have many reasons behind it: for example, if anyone needed to find the visiting apostles to request healing, it would be far easier to find them. (And speed could be important for some illnesses—though on the other hand, Matthew tells us raising the dead was also part of their commission, so …?) But I believe the interpretation I’ve most often seen reads this as a warning against moving around for nicer accommodations, which—besides being suicidally rude, and in a culture that took hospitality as seriously as the Near East!—would be gluttonous of comfort10 (even if it didn’t start out that way, the habit would be all but certain to form) and, at bottom, a total distraction regardless.

I. when you leave, shake off the dust that is on your feet for a testimony against them/when you leave there, shake off the dust that is under your feet, as a witness to them | shake off the dust from your feet as you leave that house or town. Truly, I say to you, it shall be more tolerable on the day of judgment for the land of Sodom and Gomorrah than for that town | when you leave that town shake off the dust from your feet as a testimony against them: As so often, Matthew, while the same as the other two in substance, is more poetic and elaborate, bringing in Sodom and Gomorrah—as, of all things, a positive counterexample; one is tempted to think of the abrupt and heartfelt repentance of the Ninevites.

Lot and his daughters fleeing Sodom, as

depicted in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493).11

I poked around a bit to see if “shaking the dust off one’s feet” was a pre-existing custom. Wikipedia claims it was, but without a source; something about it—I don’t quite know what—gives me “thing Christians have projected backwards onto first-century Judaism” vibes. Of course, now that search engines suck, I couldn’t find anything of use. I do know (though this is a bit different) that showing the sole of your shoe or sandal to someone is insulting in the Near East: not as bad as hitting them with it, maybe, but it’s pretty bad. This could be an elaboration of that.

Footnotes

1In heraldry, “quartered arms” are coats of arms shrunk down to one-quarter size and combined with other coats of arms. Normally (as in this example), this is done with three coats of arms: the primary arms go in the upper left and lower right quarters, and the other two in the remaining two. Here, the arms quartered are those of the royal houses of England, Scotland, and Ireland. (Dynasties—which often rule multiple nations, shift from one throne to another over the centuries, etc.—normally have separate coats of arms from nations as such.) Simplified slightly, the arms of the English monarch are Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or: “a scarlet field, three golden lions walking past but facing the observer.” Scotland’s are Or a lion rampant Gules with a double tressure of the second: “a golden field, one scarlet lion rearing within a doubled scarlet border.” Ireland’s are normally Azure a harp Or (“a blue field with a golden harp”), but here the Azure seems to have been replaced with Argent (silver, but usually depicted as white). I can’t tell if this is a variant or a trick of the light—probably the latter; Argent and Or aren’t really supposed to border each other, except on the papal arms.

2A chrismarium is a vessel for containing chrism, or holy oil, used in the sacraments of Confirmation and Unction (and on some other occasions as well).

3The Synoptic Gospels are Matthew, Mark, and Luke. They are so named because they “see together”: their structure is roughly the same (with a closer resemblance between Matthew and Mark); the actual wording of many episodes is often similar if not identical (again with more resemblances between Matthew and Mark); and none of the three overlap much with John, whose structure and style are strikingly different.

4Jacob (Ἰάκωβος [Iakōbos] in Greek, from the Hebrew יַעֲקֹב [Ya3aqov]), is typically represented in English New Testaments as “James”; Judah (Ἰούδας [Ioudas], from יְהוּדָה [Y’hudhah]), as “Jude” or “Judas” (invariably as Judas in reference to the traitor, but inconsistently when speaking about others of the same name). Simon (from Σίμων [Simōn]—or occasionally Συμεών [Sümeōn]—from שִׁמְעוֹן [Shim’3own]) is not generally altered.

5The significance of the Twelve and then the Seventy (or Seventy-Two—manuscripts vary) being sent out by Jesus may seem obscure. However, it is probably an allusion to the idea that Jesus is founding a new Israel. Twelve, the number of the sons of Jacob, symbolizes the chosen people of Israel in its wholeness (no missing ten tribes); seventy, or a number close to it, especially after twelve, evokes the Israelite caravan that went to sojourn in Egypt (as in the opening of Exodus; cf. Acts 7.8-14). More striking still is the fact that Luke sandwiches his account of the Transfiguration, which describes Jesus’ death as “the ἔξοδος [exodos]” (the departure) “he was about to accomplish in Jerusalem,” between the two missions, with the Twelve before it and the Seventy after it.

6Which, ironically, works okay for this name. But I’ve been around long enough to know, if I trust that rule of thumb from a position of ignorance even one time, hubris will rear up like Ammit to devour me. In a month I’d be arguing with some world-renowned Syriacist about how the Aramaic version of Ephesians has a clear reference to aliens in it or something.

7For the sake of being confusing, I’m sure now is a good time to note that Matthew and Matthias are slight variations of the same name in Greek, likely representing one Aramaic name.

8Oddly, even though we’ve got a bar-Jacob and a bar-Simon in there, I’ve never heard anyone even speculate on whether any of the Twelve were a father-son pair. The absence any such a tradition may be evidence against the idea. (That, and as far as being apprenticed goes, not many men who’ve already had children would have the time or liberty to go pick up a whole second profession.)

9Modern American pennies are made of surprisingly little copper, only about 2.5%; most of a penny’s weight is actually zinc. Nickels, on the other hand, are made by alloying 25% copper with 75% nickel, and thus contain way more copper than pennies, which is doubly funny given that nickels are the only coin we named after (some of) the metal they’re made from!

10Gluttony is a rather misunderstood temptation. Most of us have heard the essence of pride is self-focus, not self-aggrandizement; as Screwtape has it (Letter XIV), “[God] would rather the man thought himself a great architect or a great poet and then forgot about it, than that he should spend much time and pains trying to think himself a bad one.” Similarly, food is a shorthand for gluttony; but the real key to it is that gluttony is an unregulated appetite for sense-pleasure. Many sins we mistakenly classify as sins of lust, for instance, are so detached from any human connection (even an unhealthy one) that they’re more intelligible as acts of gluttony that incidentally involve sex than as sins of lust proper.

11The sleek, porcelain-like appearance of Lot’s wife qua pillar of salt in this woodcut made me reflect: it’s high time somebody created a set of “Lot’s wife and the city of Sodom” salt and pepper shakers.