Anyone who knows the Catholic Church would scoff at the idea of it being a safe haven for practitioners of a syncretic religion that borrowed heavily from Taoism and Buddhism and worshiped a female deity. And yet, somehow, it seemed like a reasonable conclusion to the sectarians who flocked to the Church in droves. But why did the sectarians think this? What made Catholicism seem like such an appealing option to them? There have been many theories. As we saw previously, contemporary Catholic missionaries like Franchi blamed it on sectarian perfidy and insincerity. They claimed that the sectarians were joining the Church not out of actual belief but merely to hide from the authorities. According to the churchmen, the sectarians hoped that disguising their own beliefs as Catholic Christianity would place them beyond the reach of the Qing Dynasty’s unceasing efforts to eradicate heterodox thought.

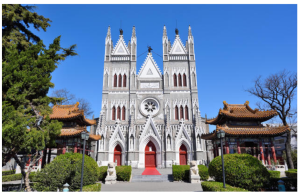

This conclusion is steeped in the same sort of condescension and self-righteousness that made the missionaries blind to the sectarian infiltration of their institutions in the first place. Still, it can seem quite logical to modern eyes. R. G. Tiedemann is willing to give the idea at least some consideration, since the sectarians sometimes did pass themselves off as members of more orthodox traditions in order to avoid the government’s ever-watchful gaze. But Catholicism was not an orthodox religion in China. It is true that there were times when the Qing court tolerated it, but there were just as many times when the imperial government persecuted it. This was particularly true after 1707, when the Papacy’s refusal to continue allowing Confucian rites among Christian converts caused the Qing to take a far more hostile stance toward the Church in China. Even during periods of relative toleration, the Qing Dynasty’s attitude could shift in an instant. Recall how swiftly Qing officials launched a persecution of Christianity in response to the sectarian actions of Zhang Paulus and his cohorts in 1714. Any fragile sense of security Catholics might have enjoyed vanished completely in 1724, when the Catholic Church was declared an illegal and heterodox sect. This edict put the Church on the same legal footing as the Three Ages sects themselves; neither had a right to exist or practice their faith in Qing China. Certainly, being a Catholic never seemed to save any suspected sect member from arrest by the overzealous authorities. Therefore, no sectarian with any understanding of the contemporary political climate could have seriously expected to find more safety in the ranks of the Church than in their own sects. Switching from one prescribed and persecuted faith to another is not a very effective strategy for avoiding persecution oneself.

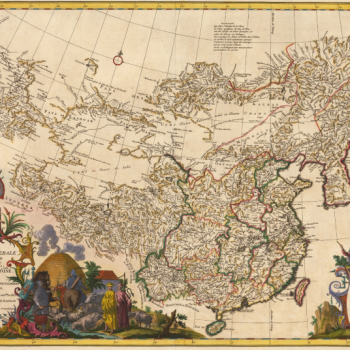

And yet, it was precisely in the years after 1707 that sect members in Shandong entered the Church in the thousands. It is hard to imagine so many of them seeing the Church as a place of safety during the most dangerous time to be a Catholic since first Jesuits had arrived in 1583. After all, reading the Qing government’s moods and knowing how not to draw its attention were crucial survival skills for the sectarians, and thus they could better sense the Church’s precarious position in China than anyone. Yang Dele would have only reached out to the Bishop of Beijing about coordinating an uprising if he thought that the Church faced the same existential crisis his own sect did. But he did reach out, demonstrating that the sectarians were under no illusions about the Church’s own level of security in Chinese society. They clearly recognized that the Church was in as dangerous a situation as their own sects were and was therefore no better placed to offer protection from the relentless specter of Qing persecution.

Besides, if safety and security were the main reasons for converting, the sectarians had so many better options at their disposal. They could have pretended to belong to more acceptable Confucian, Buddhist, or Taoist societies, or to claim that their sacred texts had been personally approved by the Emperor. These were the very things they had been doing for centuries before the arrival of the missionaries; the Jesuits themselves had resorted to similar ruses upon first landing in China. Those tried and true methods had more likelihood of success than joining a faith that the Qing government already viewed with intense suspicion. And yet, they flocked to the Church in large numbers. Indeed, they continued to do even after the prohibition of Christianity in 1724, despite there now being absolutely no measure of protection to be found in doing so. If the sectarians were only interested in their own security, they would not have continued converting after the last vestiges of Catholic security in the country were destroyed. Yet their enthusiasm for entering the Church continued unabated, meaning that the sectarians as a whole must have been inspired by some other motive to adopt Catholicism.

Furthermore, if the conversions were all an act, we would not expect Church rituals and symbols to become so popular amongst the sectarians themselves. We saw how quick the sectarians were to establish their own “Catholic Churches,” reproducing the rituals and trappings of Catholicism in a sectarian context. At least one of these sectarian churches even managed to attracted myriads of followers in a neighboring province who were not Christians. The sectarians persisted in this activity even when Catholic missionaries and Qing authorities were paying no attention to them, indicating a sincere interest in the doctrines and symbols of the Church. Even after the missionaries were forced out of China again following the 1724 prohibition, the sectarians continued to use Catholic symbols and rituals. Echoes of Christian teaching appear in later sectarian works and, when missionaries returned to Shandong once more in the 1840s, they found the folk remembrance of Christianity to still be quite strong. Indeed, they were able to parlay it into a new series of mass conversions. The survival of Christian elements among the sectarian population for a hundred years after the missionaries’ second departure indicates that the interest the sectarians took in the faith of Christ was real and abiding.

But we do not need to go as far as the 1840s to find the sectarians incorporating Christian beliefs into their own. We saw this already with Yang Dele, who claimed to be “the second person of the Holy Trinity;” Jesus Christ and God the Son. But he was not alone in a bold claim of that nature. For, as Tiedemann notes in “Christianity and Chinese ‘Heterodox Sects’: Mass Conversion and Syncretism in Shandong Province in the Early Eighteenth Century,” “it was claimed that the late Liu Mingde, founder of the sect, was God himself who had first become incarnate in Europe and afterwards in Shandong, and that was why the Europeans had come to find him and join the two religions” (371). Outside of this particular sect, He Hei’er—he who tried to convert the Pope—also got in on the act, “claiming to be the Holy Spirit who had come down from Heaven to preach God’s true law, since the Europeans refused to do so” (371). Nor were these the only such individuals that the missionaries found themselves dealing with. As Tiedemann states, “Apparently there were others who, having left the Catholic Church, claimed that they were preaching the true religion of the Lord of Heaven (zhen Tianzhuiao 真天主教), some saying they were God the Father, or the Son, or the Holy Spirit, or Our Lady (Shengmu Maliya 聖母馬利亞), all of which was evidently very confusing to Christians and gentiles” (372). Clearly, proclaiming oneself to be part of the Holy Trinity (or the Virgin Mary) had become quite the popular pastime among Chinese sect leaders.

It may well have confused the Christian missionaries and it certainly horrified them but, this late into our series, we are able to recognize a common sectarian practice that has deep roots in the Three Ages movement. Sect leaders often claimed to be the incarnation of an important deity. Usually they were a manifestation of the Primordial Buddha / Unborn Mother or of one of the three buddhas who ruled the Three Ages. Here, we find sect leaders doing the same thing, but now the divine figures they claim to be are Christian. The case of He Hei’er demonstrates that this was not simply a matter of making their own beliefs comprehensible to the Christian missionaries. It was also something they preached to their own followers, since He claimed to be the Holy Spirit revealing truths which the Catholic Church refused to. Admittedly, the sect leaders were following an ancient process; by mapping the new Christian symbols onto the apocalyptic narrative they had received from their own tradition, these sectarians were following in the footsteps of their much-earlier forebears who did the same with Buddhist terms and imagery. Still, they had to be genuinely interested in those Christian symbols in order to swap them in for the long-established Buddhist ones that all known Three Ages sects had happily used up to that time.

Therefore, we must conclude that the vast majority of sectarians who converted to Christianity were genuinely attracted to the symbols and imagery of Catholicism, even if they rejected its exclusivist demands and maintained their old beliefs on the side. Tiedemann makes the same point, stating, “It would seem, however, that outward conformity was not merely a matter of convenience and communal harmony, but was part of the extraordinary eclecticism that was so characteristic of Chinese popular religion, and even more so of sectarianism, both congregational and meditational” (368). It is true that the sectarians were very syncretic—as I have stated before, they never seemed to let a good and popular idea pass them by. But it is important to note that the images and symbols of Catholic Christianity did not slowly work their way into the web of sectarian beliefs. Instead, the sectarians took them up as soon as they heard about them. This is demonstrated by the number of sect members who flocked to the Jesuits immediately upon their entry into China and by how many sect leaders declared themselves incarnations of Persons of the Christian Trinity or the Virgin Mary in the immediate aftermath of Shandong’s post-1709 conversion boom. Christian ideas did not gradually seep into Chinese sectarianism over time, as we would expect from the natural progression of the syncretic process. Rather, the sectarians began adopting Christian symbolism and terminology, and seeking entry into the Church, at the first moment that it became possible for them to do so. Something beyond the general tendency to syncretism must have laid the groundwork for Christianity to become so popular among the sectarians so quickly.

Tiedemann recognizes this too, and offers many explanations, suggesting that perhaps it was that the sectarians hoped to gain magical protection from the deity of the new faith, because the missionaries could act as community leaders and settle disputes when the Qing authorities could not, or (citing Richard Madsen) because the specific kinds of devotional practice of the Franciscans and Dominicans reminded them somewhat of their own ritual activities. But there were many sects that offered magical protection and, as appealing as mendicant devotional piety may have been, I doubt it was enough to make a foreign faith immediately palatable to any Chinese audience. As for the influential position that Tiedemann imagines for the Catholic Church in local Chinese communities at this time—which he himself admits is a departure from the scholarly consensus—his own record of the repeated Qing persecutions of Catholics and the haughty behavior of Shandong’s Christian leaders toward the Chinese population seems to thoroughly disprove the idea. None of these hypotheses, then, provide a satisfactory explanation for the Three Ages sectarians’ attraction to Christianity. But I think that such an explanation is possible and is, in fact, the one that has been staring us in the face this whole time.

Simply put, the Three Ages sects were so attracted to Catholicism because they viewed Catholicism itself as another Three Ages sect. Its symbols might have been different from what the other sects were using, but that mattered little to the sectarians who had long practice with mixing together terms and images with diverse origins to express their beliefs. They saw no problem with using two or more different symbols from different faiths to refer to the same basic concept; hence, they happily referred to their supreme deity as the “Primordial Buddha” and the “Unborn Mother” for centuries. The new iconography brought by the Catholic Church was, in the sectarians’ minds, simply another example of different names being applied to the same ideas. From their perspective, Catholicism may have had a unique set of terms and metaphors, but the doctrines it expounded through them were identical to the sectarians’ own.

This attitude on the part of the sectarians can clearly be seen in the incidents we have discussed thus far. Yang Dele appealed to the Catholic Church to join his rebellion on the grounds that they shared the same religion. He Hei’er, while claiming to be the Holy Spirit, was apparently upset with the Catholic Church for not promulgating the type of teachings a Three Ages sect should be preaching. Liu Mingde and his followers claimed that God had manifested first in Europe and then in Shandong, and that the Catholics were the disciples of His first manifestation who had come to join with the disciples of His second. In their view, Catholicism and Chinese Three Ages belief were simply two branches of the same faith, separated by geography and not belief. Most revealing is a teaching of Liu Mingde’s sect uncovered by the Catholic missionaries themselves during their investigations: “in time the missionaries learned that the sect leaders secretly told their followers that the Catholic Church was yang 陽 and the Xinglijiao sect yin 陰, and that it was necessary to join the yin and the yang to create the perfect religion” (371). This statement deserves our closer scrutiny but for now, it is enough to state that it establishes beyond dispute that the sectarians viewed Catholicism and their faith as two halves of one religion and believed that the two needed to reunite in order for both to become whole.

Thus, it was the general consensus among sectarians that their faith and Catholicism were one religion. More than that, it seems to have been the common opinion of the Chinese public in general—or at least those members of the public who were aware of both the Three Ages sects and Christianity. As Joseph S. Sebes documents in “China’s Jesuit Century,” no less a figure than the Kangxi Emperor himself revoked his own Edict of Toleration toward Christians on the grounds that “I have concluded that the Westerners are small indeed. … It seems their religion is no different from other small, bigoted sects of Buddhism or Taoism” (qtd. in Sebes 182). Indeed, even later Christians coming to China came to a similar—if less critical—conclusion. Tiedemann himself quotes Reverend Joseph Edkins, a missionary of the nineteenth century who became involved in Hong Xiuquan’s Taiping Rebellion. Edkins, upon reading some sectarian scriptures, remarked that “there is the spirit of the gospel in some parts of these exhortations, suggesting that the writer knew the sermon of the Mount. The resemblance to Christianity is most striking” (qtd. in Tiedemann 382). We can conclude from the sectarians were not out of the ordinary in stressing their doctrinal unity with Catholicism; nearly everyone in China seemed to agree that the creeds of the two faiths were utterly indistinguishable.

Thus, we can now be certain that the Three Ages sects viewed the Catholic Church as one of their own, and the reasons for this were apparently so obvious that even Chinese society accepted the identification. What those reasons were is another question entirely. Tiedemann is aware in a vague sense that the sectarians saw the Catholics as co-religionists, and cites as a possible reason the similarity between Christianity and certain Chinese folk beliefs, asking hypothetically, “what did sectarians, and for that matter, non-sectarians, who had been ‘raised in the belief context of mother goddesses, charismatic leaders, and hope for a future savior’ make of the teachings of Jesus, the pantheon of saints and the central position of the Virgin Mary in the Catholic religion” (373). He also adds, “As Daniel Bays, writing in reference to the nineteenth century, has noted, there existed a degree of commonality in value content, structure and social role which provided a substantial common ground of identity between Chinese folk religious groups and Christianity” (373-74). Tiedemann adopts Bays’s theory that Christianity became popular in the nineteenth century because it had begun to function much like the Chinese sects as another possible explanation for why the sectarians themselves saw such a resemblance.

But we are not dealing with the nineteenth century. By that time, organized Christianity had been in China for centuries, the Protestants were around in just as much force as the Catholics, and Hong Xiuquan’s epoch-making rebellion had forever seared the Christian faith into the Chinese public consciousness. It was a completely different social situation than what Christianity faced a century before and tells little about why earlier sectarians were so quick to embrace the faith of Christ. Bays’s theory is of much less help to us in identifying the reasons for earlier sectarians’ embrace of Christianity than Tiedemann seems to think.

Tiedemann is nearer to the right track when he considers the similarities between Christianity and Chinese folk belief. But he stumbles by gesturing to popular Chinese spirituality more generally, with only a very brief nod—the “hope for a future savior”—toward the apocalyptic strain of Chinese thought that so resembled Christianity’s end-times narrative. And yet, it was precisely these apocalyptic ideas that made up the cornerstone of Three Ages thought. A better course, then, would be to look more closely at those eschatological beliefs. However, we must also narrow our focus more than Tiedemann does. Even the broader similarity between the end-times narratives of China and Christianity only gets us so far. After all, the Nestorian Christians coexisted with earlier apocalyptic sectarians and neither much influenced the other, despite the similarity of their apocalyptic beliefs. If we wish to find out why the later sectarians were so attracted to Catholicism, we should pay particular attention to those apocalyptic concepts that are unique to Three Ages sectarianism. For Catholicism appealed to Three Ages adherents specifically, and thus there must be something in their doctrine that explains the allure. Furthermore, whatever this element is, it must have a parallel in Catholic belief in order to explain why the sectarians saw the two faiths as branches of a single religion.

There are several interesting areas of overlap between Catholicism and Chinese Three Ages thought. We have already mentioned the traditional end-times narrative handed down in Chinese popular religion from time immemorial and its remarkable resemblance to that of Christianity. The Three Ages sectarians reworked that narrative, transforming it into the story of a humanity that lost its heavenly glory due to sin and of the saving mission undertaken by a compassionate deity to restore the elect to their true home in heaven. In short, the apocalyptic narrative came to even further resemble Christianity in the hands of the Three Ages sectarians. This compassionate deity, the One God, came to be worshipped in a female form, that of the Venerable Unborn Mother. The sectarian devotion to the Unborn Mother as the “queen of heaven” looks somewhat like the veneration of the Virgin Mary in Catholicism; with the caveat that Catholics do not worship Mary as a deity. Certainly, these are noteworthy similarities, but there is another which is even more fundamental. For we find in both Three Ages sectarianism and mainstream Christianity—including Catholic and non-Catholic varieties—what can only be described as a trinitarian conception of the Godhead.

The doctrine of One God in Three Persons is the bedrock of mainstream Christianity; all the other tenets of the faith flow from this initial assertion of the Deity’s triadic nature. Similarly, the Three Ages sects also believed in One God in Three Persons. It was not always the same three persons in every case. It was usually accepted that the One God (who was jointly Unborn Mother and Primordial Buddha) manifested as the three ruling buddhas of the Three Ages—Dipamkara, Gautama, and Maitreya—but the Longhua jing instead conceptualized the Unborn Mother and Primordial Buddha as two separate persons within a sectarian Trinity that also included an entity known as Heavenly Truth. But while the identities of the three persons may have changed, the Godhead was always made up of Three Persons. Nor was this a mere accident or fact of trivia; the sectarians, like the Christians, viewed the threefold Personhood of God as the fundamental embodiment of His—or in the sectarians’ case, Her—ineffable nature.

This confluence between the two faiths’ conceptualization of God is striking. It is true that it is not, strictly speaking, unprecedented in Chinese thought. Viewing the ultimate reality in the form of a triad was not unusual for the Chinese. From ancient times onward, the fundamental building block of the Chinese religious worldview was the division of the Taiji 太極 or Absolute into the dual forces of yin 陰 and yang 陽—both the ji in Taiji and yang would later become designations of the Three Ages. But the division of one into two that coexist with the one is somewhat different from both the Christian and later Chinese sectarian conceptualizations of the divine triad.

Taoism would come closer to those conceptions during the Tang Dynasty when it began to personify the Dao as a trio of deities known as the Three Pure Ones, still worshipped today as the supreme Godhead of the Taoist pantheon. One of these beings is a creation deity not unlike God the Father and another even incarnated as Taoism’s founder, Laozi, which creates a rather sharp parallel to the Christian Trinity. These deities represent many things, playing the three major roles in the creation of the universe and embodying the three energies that run through everything. The actual significance of their triadic relationship seems to be open to some interpretation but their importance in Taoism is undeniable.

Yet it was the sectarians who took the unprecedented step of making the three persons an expression of the fundamental nature of the One God, or at least how that nature is manifested in time. It is only through His / Her threefold personhood that God is able to enact the divine plan of human salvation. This is particularly evident when the Three Persons are held—as they usually were—to be the three buddhas who rule the three times; God divides history into three periods so that He / She can guide humanity to salvation in each of His / Her three identities. Due to this, the sectarian view of the Three Persons of the Godhead comes much closer to the Christian understanding of the Trinity than do other Chinese formulations of a divine triumvirate. This understanding of God’s nature is one of the things that makes the Ming and Qing sectarians distinct from all the Chinese religious movements that existed before them.

It would certainly be remarkable for the sectarians to have evolved such a similar idea in isolation. The stunning similitude between their trinitarianism and that of Catholic Christianity instead suggests a Catholic origin for the concept. But since the sectarians had already developed this view of God by the time the Jesuits landed, they must have received it from Catholicism through an earlier, hitherto-unknown route of transmission. We have seen how just such a route could have been created in the final decade of the 1200s and the first seven of the 1300s by the Franciscans who preached the gospel in China during the late Yuan and early Ming periods. But a trinitarian conception of God was not the only thing that I proposed had been brought over by those early missionaries.

It must be remembered that the sectarians and their texts present the Three Persons as the fundamental expression of God’s nature in time. The threefold nature of God is inherently a temporal one; it manifests in time as the Three Ages of universal history. God cannot be separated from the unfolding of His / Her triple nature that is the progression of time. All of salvation history is progressive and temporal because God’s own nature can only be properly expressed through the movement of time and its division into three overarching cosmic periods. The sectarians’ trinitarianism and their belief in Three Ages cannot be separated; it is their belief in the Three Ages that justifies a conception of One God in Three Persons and vice-versa. As we have seen throughout this series, it is the Three Ages doctrine, with its triadic understanding of the Godhead and corresponding threefold division of time, that gave rise to all the other developments in Three Ages sectarianism that so strongly echo Catholic and Christian teaching. Even devotion to the Mother only arose after the Three Ages had become a basic tenet of faith among sectarians. Thus, the correspondences that the sectarians recognized between their faith and Catholicism must be rooted in their belief in the Three Ages. If we could find a form of Catholic thought that also had a notion of Three Ages of progressive cosmic history and a similarly temporal conception of God, we could be certain that this was the source of all the resemblances between Catholicism and the Three Ages sects.

Anyone who has followed this series thus far knows where this is going. The Chinese sectarians’ understanding of God and history is quite alien to what now passes for Catholic orthodoxy, with its staunch insistence of an eternalist deity beyond the confines of time. But there was one movement within Catholicism that advocated for a uniquely temporal understanding of God’s nature, a school of thought that conceived of God’s threefold nature as expressing itself in time in the form of three periods of history. This was Joachimism, the intellectual legacy of Joachim of Fiore, the first person to conceive of the Three Ages of time. Among the Catholics, only the Joachimites expressed belief in a God whose threefold nature was fundamentally dynamic and temporal, the type of trinitarian deity the Chinese sectarians would later adopt. It was only they who even had a notion of the Three Ages themselves, and it was they who first made the Three Ages the bedrock of their theology. What is more, it was this very strain of Catholic thought that was so popular among the Franciscans at the time of their missionary efforts in Yuan and early-Ming China. As I have been arguing throughout the course of this series, only Joachim’s conception of the Three Ages could have given rise to the sectarian one.

This line of development is the only one that accounts for why the sectarians viewed Catholicism and their own religion as identical. Joachim was a devout Catholic, as were most of his early followers, and his writings rely heavily upon the stories and symbols of Catholic Christianity. If the sectarians received Joachimism from the Franciscans somewhere around 1300 and the recollection of Joachimite ideas continued to drive the development of their religious system for the next three-hundred years, as I have been arguing throughout this series, they would have naturally imbued something of Joachim’s original Catholicism. Joachim’s carefully crafted concordances of biblical figures and his citations of Church authorities would have been discarded in a religious atmosphere where they were of little use, but the spirit of his unique form of Catholic theology would have survived in some form. Then, when the sectarians encountered Catholicism again with the arrival of the Jesuits and other missionaries, they would have recognized some of that same spirit in these newcomers’ Catholicism—doubly so if the missionaries were once again carrying Joachim’s teachings with them, as seems likely, and concluded that the newcomers were part of the same religious tradition

This, of course, is exactly what happened. The sectarians immediately recognized that there was some inherent correspondence between themselves and the Catholics. They realized that there was something very Catholic about their faith in the Three Ages and its attendant ideas about God and salvation. The basic fact is that Chinese sectarianism was spurned by the introduction of the Three Ages doctrine to develop in such a manner that both the sectarians themselves and the wider Chinese public were largely unable to distinguish it from Catholicism. This was only possible if the source of that belief had been Catholicism and the only form of Three Ages thought in Catholicism was that which derived from Joachim. When the sectarians so adamantly insisted that their religion and that of the Catholics were cut from the same cloth, they were picking up on—however vaguely—the Joachimite connection, as were the many people in China outside the movement who considered the two faiths indistinguishable. The sectarian reaction to Catholicism’s arrival, along with that of the wider Chinese public, thus provides some of the most compelling evidence that the Chinese Three Ages concept originated with Joachim and the Joachimites.

That evidence is further supported by the specific ways in which the Qing sectarians interacted with Catholicism in Shandong. For when the sectarians invoked their similarity with the Catholic Church, it was always in reference to those features of their faith that we have identified throughout this series as Joachimite. Let us return to Liu Mingde’s statement that “the Catholic Church was yang 陽 and the Xinglijiao sect yin 陰, and that it was necessary to join the yin and the yang to create the perfect religion.” In traditional Chinese thought, yang is the active principle and yin is the passive one; yin needs the addition of yang to itself to become complete. By stating that his movement is yin and the Catholic Church is yang, Liu is thus making the claim that the Xinglijiao teaching is incomplete and must be supplemented by the further revelation of the newly arrived Church for their faith to become a perfect expression of the divine truth.

This is clearly the doctrine of progressive revelation shared by the Joachimites and the Chinese sectarians, in which later revelations expand upon earlier ones and make them more comprehensive. Liu’s insistence that Catholicism is the new revelation of the Third Age and the source of the future “perfect religion,” creates a further link back to Joachim, who held that a reformed Catholic Church would become the world’s shared religion through the insights that would be revealed in the coming era. Furthermore, Liu’s claim that the Christians specifically for the task of uniting with the Chinese and creating this new and perfect faith recalls of the global mission of Joachim’s “spiritual men” who would unite the world under an expanded and transformative Christianity. It is perhaps not for nothing, then, that Liu refers to the Catholic Church as yang, which was also the designation of the Three Ages themselves, for his vision of a union between sectarianism and Catholicism was rooted in the Joachimist inheritance shared by both traditions.

Let us return also to Yang Dele’s assertion that he was God the Son, He Hei’er’s claiming to be the Holy Spirit, and the similar insistence of other sectarians that they were the Father or the Virgin Mary. We noted how such lofty claims were part and parcel of Three Ages sectarianism. But they also were a part of more radical variants of Joachimism; we saw previously how Guglielma—or her followers, the Guglielmites—made the claim that she was God the Holy Spirit, the very assertion He Hei’er would later make for himself. Indeed, it is not impossible that it was the Guglielmite insistence on viewing God as female—or that of other women and groups of a Joachimite persuasion—that served as the ultimate source of the female God of the sectarians rather than the Virgin Mary or the Queen Mother of the West. Regardless, this was another area in which the sectarians seem to have been drawing upon their own inherited Joachimism as a guidepost for understanding the newly arrived Catholic faith.

The ease with which these sectarians swapped out Buddhist figures and symbols for Catholic ones shows that they viewed these symbols and figures as equivalents, despite their originating in different faiths, and were more than happy to replace those of one religion with those of another whenever it seemed useful and appropriate. This explains how Joachim could have had such an influence on the sectarians despite no traces of Christianity appearing in the baojuans. If the sectarians so easily swapped out their long-held Buddhist iconography for a Christian one when they encountered the missionaries, they could easily have done so in reverse some centuries earlier when the Franciscans departed. Left in a milieu that was largely Buddhist with very few remaining traces of Christianity, the sectarians would naturally have reverted to the prevailing cultural iconography to get their message across.

Indeed, this is exactly what happened when the missionaries were expelled from Shandong in the 1730s. As we saw above, Joseph Edkins testifies that when Christian evangelists returned a century later, they found that contemporary sectarian texts contained portions of the Sermon on the Mount. However, Edkins says that those passages are “reminiscent” of Christ’s words, not that they are actually Christ’s words themselves. This suggests that the sectarians kept the message of the Sermon on the Mount but got rid of all the Christian trappings, including the figure of Christ, in order to fit more comfortably into the non-Christian atmosphere of post-missionary Shandong. They were surely capable of doing the same thing hundreds of years earlier when it came to preserving Joachim’s ideas. In this light, the underlying correspondences with Joachim, such as the sectarians also making the rulers of the three time periods aspects of God and identifying them with major figures of the prevailing faith, are a better gauge of his influence than whether the names they used for those figures were Buddhist or Christian. That being said, the fact that the sectarians in Shandong identified the Christian Trinity with the One God and the rulers of the three ages in their own belief system perhaps indicates that they remembered Joachim’s original Christian iconography better than they let on.

This last point is worth dwelling on a little further. After all, what is so suggestive about these Joachimite themes is that the sectarians expressed them not only regarding the Catholic Church but also directly to the Church itself. This indicates that they expected the Church to recognize those various features and acknowledge that it too held the same beliefs. The sectarians would not have thought this if they only had first-hand knowledge of the Church itself to go on. Even with the mistakes of missionaries like Francesco Nieto, they should have quickly realized that the Church did not look kindly on the tenets of their faith. But their expectation that the Church would share their doctrines makes more sense if the sectarians remembered that those teachings originated in the Joachimism preached by an earlier generation of Church missionaries. If they did, they would naturally assume that the later Church would hold the same Joachimite opinions as the earlier churchmen and would thus welcome them with open arms. This suggests that the sectarians’ embrace of Catholicism was not simply due to general similarities between the two religions but came about because they specifically recognized Catholicism as the source of their own concept of the Three Ages. This means in turn that, improbable as it seems, the Three Ages sectarians did in fact retain some genuine knowledge of Joachim and his original doctrines even after centuries without contact from the Catholic West.

Indeed, if we return to the words and actions of the Shandong sectarians, we find statements Recall what Liu Mingde—or his disciples—had to say about God becoming incarnate first in Europe and then in Shandong. This seems like a reference to the incarnation of Christ. But Jesus was born, lived, and died in Judaea, beyond the bounds of Europe; if the sectarians were referring to him, they were speaking nonsense. Their words become perfectly intelligible, however, if we assume that he was talking about the origins of the Three Ages doctrine itself, which did indeed begin in Europe—Joachim himself was a lifelong resident of Calabria in Italy—but then came to China. Shandong early on became one of the hubs of this new system of thought, fostering its further development and exporting it to the rest of China. Thus, when the sectarians stated that their beliefs originated first in Europe and then in Shandong, they managed to correctly identify the actual route of transmission by which Three Ages thought came to the country. It is difficult to imagine them doing so without some awareness of Joachim and the school of thought he founded.

Recall also the example of He Hei’er, who claimed “to be the Holy Spirit who had come down from Heaven to preach God’s true law, since the Europeans refused to do so.” From Tiedemann’s brief summation, it sounds as though He preached that the Holy Spirit was bringing a new revelation beyond that found in the contemporary Catholic Church, and that this new insight would act as “God’s true law,” the complete doctrine of divine truth that had not yet been fully unveiled. Aside from He’s evident hostility toward the Church, this is an exact restatement of Joachim’s own position on the new time of revelation: it would be the age ruled by the Holy Spirit in which new truths that went beyond contemporary Catholic doctrine would be made known. He’s reproduction of Joachim’s thought is simply too precise and perfect for him to have come across it by coincidence. He too must have had some knowledge of Joachim and his authentic teachings.

The fact that these apparent nods to Joachim himself appear in the context of the sectarian encounter with Catholic missionaries brings up another set of questions. If the sectarians thought that the missionaries would react so well to their Three Ages teachings, was it because the missionaries still professed their own belief in the Three Ages of time? Did the missionaries once again bring Joachim’s thought with them from the West? Did some of those missionaries share their beliefs with the sectarians and was this the cause of the apparent reacquaintance with Joachim that we see in sectarian thought at this time? Were the sectarians misled by the Joachimism of certain missionaries to conclude that the Catholic Church on a whole shared these beliefs and was hence not so different from their own sects? I would say that the answer to all of these questions is yes, and this is at least part of the reason Catholicism appealed so strongly to the sectarians. For it is indeed very likely that these missionaries carried Joachim’s teachings with them to China, just as their forebears surely did a few centuries before. Perhaps it was even missionaries with Joachimite sympathies who first chose to focus on preaching to the sectarians because of their similar conception of the Three Ages, sparking the sectarian fervor for Catholicism that subsequently inspired the Church at large to prioritize converting the members of these sects over everyone else.

After all, the Franciscans were in Shandong while all these events were occurring—indeed, they were central players in these strange incidents—and Joachimism had certainly not disappeared from the order, even if it was less prevalent than it once had been. Furthermore, Tiedemann briefly notes the existence of one Bernardino Bevilacqua della Scala, a Franciscan whose lasciviousness—always the particular sin of Catholic churchmen—brought the order into much disrepute in the region. This Father Bernardino was a Calabrian, so we know that there were Calabrians serving as missionaries. The example of Tommaso Campanella, the author of The City of the Sun, in Europe demonstrates that it was usually the Calabrians, hailing from Joachim’s home region, who held his memory in particular regard, even at this late date. One also wonders if missionaries like Nieto and Orazi were criticized for preaching poor theology to the sectarians in part because they were sharing and exchanging Joachimite ideas with them.

Whatever the case, we can be reasonably confident that Joachimism in some form was spreading through Shandong and China at large. Tiedemann asks the question, “Given the type of missionary that had been operating in Shandong (i.e., Franciscan) and the way in which the Christian message had been propagated and received, can we speak of the emergence of a kind of Chinese ‘folk Christianity’, something rather different from theological orthodoxy promoted in distant Rome?” (379). We can now answer in the affirmative and say that there a folk Christianity at variance with Catholic orthodoxy operating in China. We can further state that it was in all probability spread there by the Franciscans. But we can go even farther than Tiedemann and say with some confidence that this folk Christianity—which appealed so much to the Three Ages sects—was Joachimite.

This avenue of influence offers a simple and persuasive explanation for why sectarian baojuans written from the 1640s onward show a much greater fidelity to the ideas of Joachim and his followers than earlier ones do. The Jesuits had spread throughout China by 1601 and the Franciscans and other mendicants arrived in the 1630s. Thus, some of them could easily have encountered Gongchang and introduced him directly to Joachimite ideas; Gongchang’s interest in all religious traditions suggests that he would certainly have been receptive to their message. The fact that the Longhua jing contains both a particularly Joachimist understanding of progressive revelation particularly close and Fra Dolcino’s conception of Four Ages, in addition to a more general call for the unity of all faiths, suggests that such an encounter might very well have taken place.

Similarly, that the Dudou litian baojuan not only follows Joachim in associating the Three Ages with three different modes of life but even includes the exact same three modes as the abbot himself—only reversing the order they come in—can also be explained by the possible influence of Joachimite missionaries. After all, the Dudou litian baojuan is a product of the eighteenth century, the same period of time that Catholic missionary activity in China was at its height and the cross-pollination of Catholic and sectarian thought was occurring in Shandong and elsewhere. Its author or authors could have easily encountered Joachim’s ideas about the three ways of life that characterize the three time periods in this fertile religious climate. Indeed, it is likely that they did since, as is the case with He, their reproduction of Joachim’s thought is too exact to be anything but a direct borrowing.

Let us consider another eighteenth-century text, the Gufo danglai xiasheng Mile chuxi baojuan (古佛當來下生彌勒出西寶卷), whose title either means Precious Scroll of the Primordial Buddha Carefully Explaining the Coming of Maitreya (if the text is mistaking xi 西 “west” for xi 細 “careful,” a homophone used in a similarly-titled baojuan) or Precious Scroll of the Primordial Buddha Regarding the Imminent Arrival of Maitreya from the West (if the title is accurate, it references the use of the Western Paradise as a common metaphor for the Unborn Mother’s Heaven). The Gufo danglai baojuan contains a depiction of the Third Age that Daniel Overmyer, in Precious Volumes, summarizes thusly,

There will be more immediate practical benefits as well–lost items will not be picked up from the roads and there will be no thieves or bandits, nor will there be any royal law, or officials, or taxes of grain or silver. In every household men and women will recite scriptures, with religious practitioners everywhere. Wives and husbands will not remarry, and there will be a feast every noon and beautiful clothes to wear! (Overmyer 277)

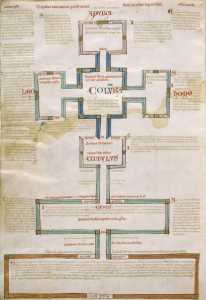

This is a far more down-to-earth vision of the Third Age than the flights of fancy we see in some earlier works such as the Puming baojuan. There is no ambiguity here about the nature of the coming time; it is clearly a utopian future age of this world rather than an otherworldly paradise beyond the current universe’s temporal bounds. This makes it look very much like Joachim’s own vision of the Third Status. Indeed, even certain features of this age seem to reproduce details from Joachim’s own description of the third era of time. In the Gufo danglai baojuan, there is no government or secular authority; Joachim talks little about secular government, implying that he either thought that it would not exist or would take a back seat to the authorities of the monks who would guide the community. The lay households where men and women recite scriptures in the Gufo danglai baojuan recall the role of lay community in Joachim’s ideal future society. As sketched out in Joachim’s Liber Figurarum, families of men and women would piously live together at the outer bounds of the monastic structure under the supervision of a monastic spiritual director (see Liber Figurarum, Plate XII). What we have here, then, is another sectarian text that both dates from the moment in time when Catholic missionary outreach to the sectarians was at its height and appears to contain traces of genuine Joachimite thought. This and the example of the Dudou litian baojuan suggest that the authors of some eighteenth-century baojuans had direct access to Joachim’s teachings, and the Catholic missionaries were at the time the only possible avenue for this to occur.

Additionally, we know that an authentic form of Joachim’s thought did indeed make it to China at some point before the twentieth century, for his subsequent influence on indigenous Chinese Christianity has been well documented. Lian Xi, in “The Search for Chinese Christianity in the Republican Period (1912-1949)”, considers the figure of Watchman Nee, an influential evangelist in the first half of the twentieth century who hailed from Guangdong and founded a major denomination commonly known as the “Little Flock.” According to Lian, Nee preached “an elaborate form of premillennialist dispensationalism, which divides human history into three successive divine dispensations— the present being the ‘Age of the Church (or Grace)’ before the arrival of the ‘Age of the Kingdom’ (Lian 885), with the first age being the Age of the Law. Lian further remarks, “In its earliest form Christian dispensationalism was expounded by the twelfth-century monk Joachim of Fiore (ca. 1135–1202)” (885) and adds in a footnote, “Nee’s theory clearly derives from that of Joachim, with slight modifications” (885, n. 123). That such an important figure in the development of Chinese Christianity chose his ministry on Joachimite ideas shows how strong of an influence Joachim’s thought had come to exert in the country by the first decades of the twentieth century.

Through his evangelical work, Watchman Nee extended the reach of the Joachim’s ideas even further. He also followed another Joachimite pattern: women played a significant role in his spiritual life. The preacher who brought him into the faith was a woman, as were all of his intellectual mentors. Nee’s movement has continued to have a Joachimist and often female-centric undercurrent up to the present time. This has had a particularly unpleasant manifestation in more recent times, as Lian notes, “One leading sect, a spin-off of the Little Flock, was started in the early 1990s by a North China woman who claimed to be Christ returning to earth in a female body to usher in the ‘Age of the Kingdom’—the third and last age of Watchman Nee’s dispensationalism” (897). This organization, with a Joachimite theology remarkably reminiscent of that espoused by Guglielma and the Guglielmites, is the infamous Eastern Lightning. Their atrocious activities need not concern us here; suffice to say, Joachim, with his peaceful theology, would never have approved of their actions. But the hold which this group has on Christian sectarianism in the country proves, if nothing else, that Joachimite ideas are very much alive and well in China’s indigenous Christian scene.

The last decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth represented the moment in time when Christianity began to catch fire with the Chinese public for the first time. It was an era when indigenous preachers began to innovate with their doctrines and messaging in the hopes of winning converts. But rather than being one of these innovations, Joachimism—in its original form and not that of the Three Ages sects—was already a fundamental part of Chinese Christianity This means that it must have been circulating in China for quite a while, which gives us even more reason to think that it had come in with the Catholic missionaries, possibly being reinforced by some of the Protestant missionaries who came to China in the nineteenth century. This would give the authentic Christian form of Joachimism they introduced plenty of time to root itself in the Chinese religious landscape.

The shape of Chinese Christianity itself might also testify to the exchange of Joachimite ideas between missionaries and sectarians. The new Christian sects founded in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries owed a debt to the work of the foreign missionaries but also tended to inherit many features from their non-Christian sectarian forebears, such as the relatively greater role played by women—some of whom have even claimed to be manifestations of God—and the same basic end-times scheme that has existed in Chinese apocalyptic thought for millennia. The overlap of Christian and sectarian influences is illustrated by a curious incident recounted by Lian: when the True Jesus Church—a native evangelical congregation—splintered following the death of its founder, one of the splinter groups was “‘The Church of the Heavenly Mother’ (Tianmuhui), led by a woman who had apparently fashioned a Christian variant of the millenarian White Lotus belief in the Mother of No-Birth” (861). Lian’s improper use of the “White Lotus” term aside, this shows that the new Chinese Christianity was something of a merger between Three Ages sectarianism and the forms of Christianity brought to China by the Western missionaries.

It seems that once the cultural pendulum switched from Buddhism to Christianity, many sectarians were happy to apply Christian symbols to their faith instead of Buddhist ones, as we earlier supposed they would. One wonders, too, if this charge was led by any of the sectarian “Catholic Churches” that so bedeviled the missionaries in the eighteenth century or their descendants. Still, we can suppose that the interplay between the Christian and sectarian forms of Joachimism had much to do with these developments. For a faith with its feet in the two camps of Christianity and Three Ages sectarianism is exactly what we would expect to emerge in China’s syncretic religious climate if the missionaries and the sectarians engaged in a genuine intellectual exchange based on a shared idea. And the only shared idea that could have served as such a basis was, again, the Three Ages concept itself.

We thus have good reason to think that the Catholic missionaries did import the original Christian form of Joachimism back into China during the late-Ming and Qing-era missionary efforts and brought them to the sectarians, who recognized the similarity to their own doctrines and thus used Joachimite teachings as a reference point in their own religious thought. That being said, we cannot discount the possibility that the sectarians remembered more of the earlier Franciscans’ Catholic Joachimism than it seems and that this helped to facilitate their intellectual relations with the later missionaries. Both scenarios could account for why the sectarians became so certain that the Catholic Church shared their belief in the Three Ages. But in either case, it is Joachimism was the decisive factor in convincing the sectarians that the Catholics were their co-religionists. That the sectarians universally recognized Catholic Joachimism—and through it, Catholic doctrine as a whole—as being identical to their own beliefs provides compelling evidence that the Chinese doctrine of the Three Ages did indeed originate from Joachim’s own, spread to China by the early Franciscan missionary effort.

Thus, given the weight of all the evidence presented in this series, the only reasonable conclusion is that Joachim’s ideas did indeed travel from Italy to China with the Franciscan missionaries who arrived at the Yuan court around the year 1300. From there, the Franciscans spread them to the common people of the region around Beijing. Since this was the social class most likely to involve themselves in apocalyptic movements, Joachimite concepts soon entered popular Chinese eschatology and became the basis upon which all later end-times sects were built. These sects would take up the Three Ages teaching pioneered by Joachim and make it into the core of their faith. It would remain the bedrock of their beliefs ever afterward, with monumental implications for later Chinese history.

Acknowledging Joachim’s role in shaping their religion takes nothing away from the sectarians themselves. All their beliefs came from somewhere, after all, and we must still marvel at the inventiveness and ingenuity they displayed in mixing Joachimism into an already heady stew of Buddhist, Taoist, and popular folk beliefs and producing a serviceable belief structure from the resulting concoction. But it does demonstrate that the allure of Joachim’s Three Ages idea was far greater, and its reach far broader, than anyone has dared suspect; even his considerable impact on the development of the Western world only amounts to a portion of his total influence. For, despite being stripped of its overtly Christian underpinnings and dropped into a culture so utterly unlike the abbot’s own, his innovative theological system took root in this foreign soil and thrived. Indeed, for centuries, it was the only part of the Christian message that did.

The only possible alternative is that the Chinese sectarians really did create a system that they themselves would later acknowledge to be uncannily similar to Joachim’s own, without any form of transmission or intermediary contact between them. And that, as I have said, would be one of the most astonishing coincidences in the whole history of religions. In that case, one would almost have to conclude that some supernatural agency was at work, willing to concept to be born into the world with such force that it appeared in two vastly different societies situated halfway around the globe from each other. I am not sure that most people are ready to face the implications of such a conclusion. Still, whichever argument one prefers, it is impossible to deny this astonishing fact: the remarkable concordance between Joachim’s original Three Ages concept and that of the Chinese sectarians must necessarily transform our understanding of the development of religions across historical time.

Works Cited

Overmyer, Daniel L. Precious Volumes: An Introduction to Chinese Sectarian Scriptures from the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Tiedemann, R. G. “Christianity and Chinese ‘Heterodox Sects’: Mass Conversion and Syncretism in Shandong Province in the Early Eighteenth Century.” Monumenta Serica, vol. 44 (1996): pp. 339-382.

Xi, Lian. “The Search for Chinese Christianity in the Republican Period (1912-1949).” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 38, no.4 (October 2004): pp. 851-898.