In my last column, I wrote that we (the United States) are becoming less religious. It prompted a good deal of discussion and most of it was civil. That is one of the goals I have for this column: civil discussion about important issues.

In my last column, I wrote that we (the United States) are becoming less religious. It prompted a good deal of discussion and most of it was civil. That is one of the goals I have for this column: civil discussion about important issues.

I’m following up that article with this one which will address the question of “Why.” Why are people leaving their religious faith and traditions behind? It is less researched than the phenomenon of de-churching, which is plain to see.

I’ll offer up three buckets of reasons why this is happening.

Leaving one’s religious beliefs and affiliation behind is a personal decision. Each person has their unique reasons for ditching a belief system which in some cases, they’ve known their whole lives. So, to try and generalize too far about why millions of people in the United States have decided to do so over the past three decades may be fraught with error and oversimplification. But let’s give it a try, shall we?

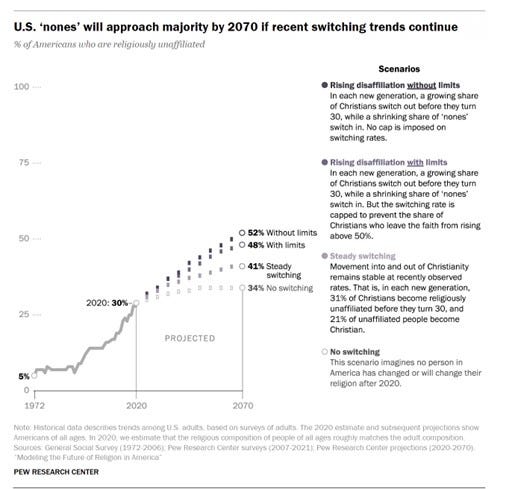

How many people are we talking about? According to a September 2022 Pew study, people identifying as Christian have decreased from 90% of the U.S. population in 1972 to 64% in 2020. And in the aftermath of the COVID crisis, that number is now lower. Those identified as “none” comprise roughly 30% of the population. So, three out of ten Americans no longer identify as a Christian or “religious.”

The future for religion doesn’t look much brighter. If the current trends continue, researchers estimate that by 2070, less than 50% of the US population will still be identified as “Christian.”

Well, this certainly has ramifications in every sphere of culture, society, and our institutions. But let’s get back to the fundamental question of why.

Why are people leaving the church? Researchers are on this, and there are a few good studies that have identified dozens of reasons given

by those who have been interviewed.

Why I Left Evangelical Christianity

Since no one has interviewed me, I’ll offer a first-hand account of my decision to leave Christianity behind. It happened around 2006. My experience was a slow, gradual migration out of the evangelical circles I had lived in for over 40 years. I was “born-again” in 1964 at a Billy Graham Crusade, and until 2006, I identified as an evangelical. I taught in private Christian schools and participated in various local conservative churches as a teacher and youth sponsor.

Over the years I developed what I called, “evangelical fatigue.” It was a combination of factors that are common within evangelical communities. You had to accept other people’s religious interpretations as more valid than your own; oppose rational science; pretend to be something different than a normal human on Sundays while attending church; learn to speak the secret language that evangelicals use; and generally, work hard to gain the approval of God, pastors, and other people. It was exhausting.

But I’ll point to two major factors beyond just general evangelical fatigue with the religious system that ultimately led to my exodus out of the church. The first was the politicization of evangelical churches and the second, was a lack of empathy and concern for personal pain during a difficult time in my life.

I was confronted as early as 1980 with the sage advice that I better be voting for Ronald Reagan that year if I were a “good Christian.” That was rather shocking to me since many evangelicals had voted for the Democrat, Jimmy Carter in the 1976 election, including me. Carter was the Baptist Sunday School teacher who was faithful to his wife and spoke of being born again, while Reagan was the divorced nominal Presbyterian (no disrespect to Presbyterians) who seldom attended church. Yet my faith was called into question if I supported Carter. This made no sense.

But the evangelical faith continued unabated politicization over the next 20 years with each year getting worse. By the early 2000s, evangelicals had taken over many Republican Party state and local organizations, especially in Iowa. They infused politics with a winner-take-all, apocalyptic mindset that demonized their opponents and pressured any evangelical who had a different policy position than the Republican Party. They were called RINOs. It was becoming apparent to me that the “church” was by then set on a trajectory toward pure political power at the expense of any meaningful “good news” that was related to the teachings of Jesus. In fact, by then Jesus was an afterthought, if that.

But there was another issue for me that had surfaced by the early 1990s. Politics was certainly concerning, but I faced a personal crisis in 1993 that ended up in a divorce from my first wife who was also the mother of our two children.

Divorce was an existential crisis if you were involved in any sort of Christian ministry. Instead of reaching out with care, support, and help, both my ex-wife and I were subject to judgment and dis-membership in the leadership roles we had at the time in our respective evangelical ministries. The divorce was amicable, and we tried to do what was best for our children, but the evangelicals in our lives seemed more interested in the “compromised role model” we had become. Shaming someone in distress was more important to them than loving someone in a crisis.

That event along with the disillusionment of the political motivations of evangelicals set me on a private journey of personal reflection, doubt, and questioning over the next decade or more. Those are three things evangelicals do not want you to do: think for yourself, doubt what you’ve been taught, and ask difficult questions. But I did, and by 2006, I became aware that I was no longer part of the evangelical community. I just couldn’t do it anymore. I wasn’t angry at anyone, and I didn’t leave in a huff. I just in good conscience could no longer call myself an evangelical. I had moved on and finally admitted it.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was part of a growing number of people who were experiencing a similar thing. I didn’t know about the “nones” in 2006 and I didn’t hear that term until much later. However, my experience has paralleled the experience of millions of others who came to terms with their evangelical mindset and found it lacking.

Another descriptive term I learned later was “deconstruction.” I had deconstructed my faith but rather than leave the pieces lying around, I reconstructed something for myself that has proven to be much more rewarding, fulfilling, and satisfying. It isn’t a new belief system or religion it is the opposite. It is the rejection of relying on a belief system to find connection and meaning in my life. If you want to read more about this, I will point you to my book, Confessions of a Recovering Evangelical. I hope you will check it out.

The Three Buckets

The reasons people have given to researchers about why they left religion or Christianity in particular, although broad and varied, can be categorized into the three groupings that I experienced: personal harm and institutional dissatisfaction. The third is what I will call intellectual incongruence. Most reasons people give can be tossed into one of these three buckets.

I will use these three categories to share what the limited research has discovered about why people leave their religious institutions. In short, these three categories tell us much about what the evangelical church has become as an institution and how it has abandoned its true calling of loving people.

Evangelicals blame everyone else for people leaving their pews as if it were a grand conspiracy, but it comes down to what they have become as an institution and how they treat people. That’s it…it isn’t the libs or the Marxists or the secularists who are out to get them. If evangelicals are hemorrhaging people from their churches, it would be best for them to engage in the three things they seem to dislike most: reflection, doubt, and questioning. Something tells me they won’t go there.

Bucket #1 – Institutional Dissatisfaction

One of the more insightful studies I have run across was an article by a journalist-former evangelical, Brandon Flanery in 2022. It was published in the Baptist News Global entitled, “I asked people why they’re leaving Christianity, and here’s what I heard.” He gathered data from 1200 people asking them a series of questions about their reasons for leaving the Christian faith. Flanery created a coding system for the responses he received and was able to quantify the results. What he found was not unpredictable, but it did suspend a few myths about those who are leaving.

Those within the evangelical church are well aware of the rapid decline of church attendance especially by millennials. Their analysis and recommendations lack deep self-reflection. Instead, they blame churches for having “resorted to entertainment, performance-oriented singing groups, and shallow teaching that will not stem the exodus of the younger generations from the church.” (Answersingenesis.org) The truth is much more complicated than simple stylistic or cosmetic changes.

Take a look at this graph from Flanery’s study:

Even the Methodist Church, one of the nation’s largest denominations, has split over this issue. In January 2023, Christianity Today reported that the Methodist Church has lost over 1800 congregations over this issue. Right here in my state of Iowa, 83 churches have split from their Methodist denomination so that they can continue to exclude some people they don’t like.

There are similar results as you look through Flanery’s list related to women’s rights, civil rights, and the Us v. Them mentality. As an institution or faith community, the evangelical church has become so tribal that they would rather exclude people from their fellowship and partnership instead of loving and including them. In other words, the evangelical church is so steeped in patriarchy, unconscious racism, and hate for the gay community that people are simply walking away.

Politics is high on the list too. The evangelical church as an institution, has become not just politicized but MAGAized over the past 8 years, and for many, it is another deal-breaker. As Flanery points out this is the issue that “broke the camel’s back.”

Bucket #2 – Personal Harm

The next bucket is related to personal harm, and it shows up in the results in a major way. Categories like behavior of believers, pain, abuse, and mental health all reflect the dissonance of a faith group that is called to love everyone, yet inflicts damage, harm, and even trauma on those within their congregations. This type of personal and psychological harm has given rise to a whole new area of support called “religious trauma counseling.” There are trained clinicians who help former churchgoers deal with the hurt and pain inflicted on former congregates.

You don’t have to scroll through Face Book groups very long like “Exvangelicals” or “Recovering Evangelicals” before you read personal stories from real people about how they suffered humiliation, abuse, and shame at the hands of those who claim to represent God.

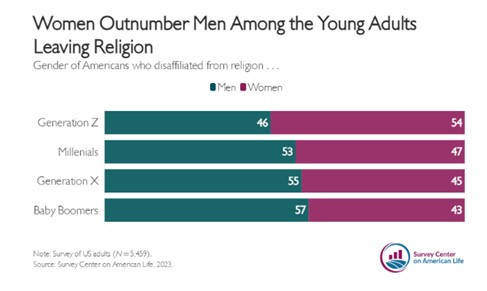

Women are especially subject to this type of religious trauma which many times plays out in their marriages.

I’ve heard from more than one female “leaver” about the shame and humiliation they experienced when they went to church leaders for counsel about an abusive husband. They were told they couldn’t leave him, and they should just pray harder, be submissive, and stay in the marriage. It is a costly mistake.

I’ve heard from more than one female “leaver” about the shame and humiliation they experienced when they went to church leaders for counsel about an abusive husband. They were told they couldn’t leave him, and they should just pray harder, be submissive, and stay in the marriage. It is a costly mistake.

The Survey Center on American Life has published this data about women being more likely to leave their religious faith than men, especially in Gen Z. This is a turnaround, but it isn’t surprising. Look at the graph:

I suspect this trend will continue and accelerate in the coming years.

Bucket #3 – Intellectual Incongruence

The third bucket is intellectual incongruence. Several categories on the graph can be placed in this bucket. Intellectual integrity, education, theological issues, and others reflect the problem many encounter when trying to “fit in” to a religious community at the cost of common sense, scientific methodology, and evidence. It requires the suspension of disbelief to force yourself to believe in many doctrines of the church. In an age when having vast amounts of information and counterviews in the palm of your hand, churches can no longer be the sole source of truth.

Claims of having the sole source of all truth in an “inerrant and infallible Bible” are easily contradicted by even a cursory reading. Yet, evangelicals defy logic by appealing to their highest authority even when it is nonsensical to do so. I have a chapter dedicated to this topic in my book (another shameless plug).

A personal story will help illustrate this point. At one of the last churches I attended, I was a volunteer youth sponsor. During one lively discussion session, a few of the students began to ask me questions about their church’s faith statements. They wanted to know why Christianity was the “only correct religion” while millions or even billions of others in the world worshipped a different way. They questioned the Bible as the only source of truth, and they questioned why evolution was considered wrong when it was clear to them the evidence was against creationism.

At first, I was inclined to give the same pat-apologetic answers that I had given to students for decades before. I went into defensive mode, but their sincerity and honesty overcame my need to be right. This was very close to when I decided to leave the church behind, and these students helped me see that the answers weren’t really answers. They were tired, worn-out statements of archaic ideology that simply couldn’t be defended. I eventually gave up my lame attempts to give finality and certainty to their questions and simply said, “Those are good questions…keep asking them.”

Leaving one’s religious beliefs and institutions after having identified with them for so long can be a scary and difficult path. Perhaps one of the most difficult tasks is to begin to redefine who you are without the religious label, jargon, and belief statements. For me, it was learning to redefine myself in a whole new way…as a human. Just being a human with no other labels. That will be the topic of my next column…stay tuned.