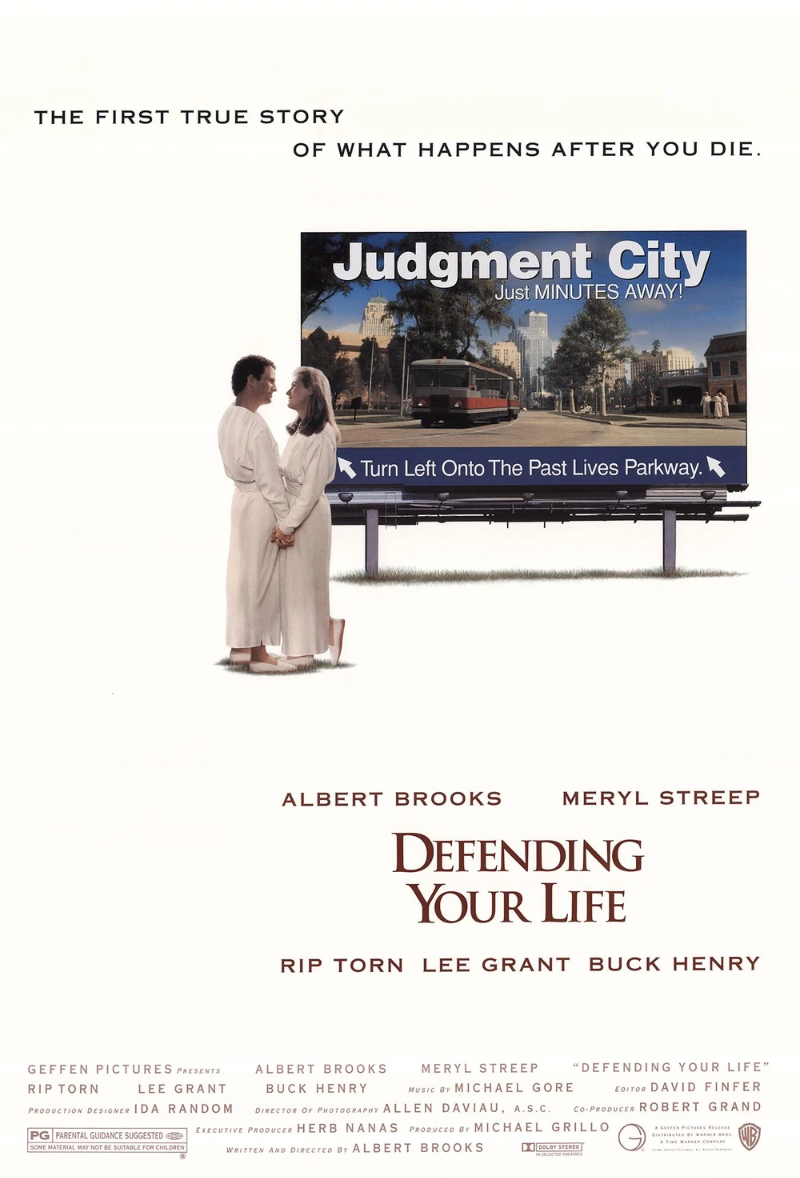

Faith on Film is a monthly feature published the last Sunday every month.

If movies were meals, Defending Your Life has enough familiar ingredients to satisfy the palette of just about anyone craving comfort food. This is a high concept film that is so farcical, every scene is filled with hilarious observations. Of course, this is no mistake: the genius of actor/director/writer Albert Brooks lies not merely in comedic timing or context, but something that’s increasingly rare in cinema these days: pathos.

Pathos is considered to be a method of persuasion that, rather than appealing to your logic (logos) or your morals (ethos), speaks to you in a way that provokes an emotional response: you are compelled to care…to feel. It’s a word that for good reasons has been widely used to critically describe the films of Charlie Chaplin, and certainly, Defending Your Life would have been a movie Chaplin would have loved to create. In spite of its absurdity, it is impossible to not identify with the feelings the characters experience during the course of Defending Your Life.

Here’s the film trailer:

Something’s Coming

Daniel Miller (Albert Brooks) is a quintessential late 80’s West Coast yuppie. On his 39th birthday, he leaves the office early to pick up a birthday present he bought himself, a BMW 325i convertible. While driving away from the dealership, he’s enjoying himself with the top down and the music cranked up (appropriately, “Something’s Coming” by Barbra Streisand), when a stack of CDs his fellow office mates gifted him goes sliding off the passenger seat. As Daniel leans over to gather them up, he accidentally crosses into oncoming traffic and hits a bus head-on.

Instantly, he along with a procession of dozens of other (mostly elderly) people in matching white hospital gowns are whisked by conjoined wheelchairs through some commercial terminal onto open-air trams like you would find at a large amusement park. While the scenery along the short trip is generic and non-descript, ahead lies a metropolis of office parks and high rises.

Arriving at a hotel, he and his fellow dearly departed are escorted to their rooms and advised they should not worry about a thing and just go to bed. And Daniel certainly looks tired—indeed he cannot even muster a word at this point, but yet searches pockets that are not there to tip his attendant money he no longer has.

Little Brains

Apparently, for most people, the afterlife has a stop along the way, and that’s where we find ourselves along with Daniel: Judgment City. He is there to defend his life, as Daniel’s avuncular defender Bob Diamond (Rip Torn) calls to explain the next morning.

The process is similar to a trial, with a prosecutor, and a panel of judges. After each person’s life, their decisions and events are examined to see if they should go back to earth and repeat the process, or proceed forward, whatever that means.

Diamond’s hearty, reassuring manner doesn’t calm Daniel, and that could have something to do with how he describes the plight of humanity: “Everybody on earth deals with fear; that’s what little brains do.” The problem is humans only use about 3 percent of their brains, so most of us devote our lives to fear. As we “get smarter” we move past fears, and move on from earth as well. Or as Bob Diamond puts it, “Fear is like a giant fog. It sits on your brain and blocks everything: real feelings, true happiness, real joy. They can’t get through that fog. But you lift it, and buddy, you’re in for the ride of your life.”

This should inspire a degree of hope in Daniel, but all the constant talk of brain size by others, especially Bob Diamond, leads him to remark, “I’ve just came from a world filled with penis envy, now I’ve got a world with brain envy.”

The Good Place

Still, Judgment City is actually much less imposing than it sounds. Those defending their lives are given identical white, flowing robes called Tupas to wear, which somehow always look remarkably flattering. There is no money, and the weather is a constantly clear and sunny 74 degrees.

The hotel TV plays soap operas and game shows about the afterlife, restaurants look like they would just about anywhere in the United States, only the food is terrific, available instantly, and doesn’t make you fat. Bob Diamond’s gray office is so mundane and ordinary, it could belong to any large, boring, corporation (think Office Space or that open office floorplan of The Crowd). As one character explains, Judgment City was designed to be as much like earth as possible to make the process of judgment “as stress-free as possible.”

Despite these efforts, Daniel’s prosecutor Lena Foster (the always convincing Lee Grant), inspires much stress in Daniel’s afterlife. Bob Diamond calls her the “Dragon Lady,” and it’s not difficult to see why. Before the proceedings even begin, Lena narrows her eyes and points at Bob Diamond menacingly and says, “I’m going to get you. I promise.” Sheesh.

Death Becomes Her

Along the way, at a comedy club, Daniel meets a woman about his age named Julia (Meryl Streep). They hit it off instantly and are obviously attracted to one another, but Daniel senses something different about Julia. There is a confidence she has that tends to bring out his own insecurities. Soon, he begins to notice how her hotel is much nicer than his, how her defender is more competent, and even her trial is a series of encouraging reflections rather than a mandatory accounting for a lifetime of poor judgment.

Meanwhile, Daniel’s trial isn’t going very well. Before a panel of judges, for four days Lena replays moments from his life to demonstrate how he has allowed fear to dominate his choices, always for the worse. These vignettes are sometimes heartbreaking and often hilarious. We follow Daniel from a sometimes abusive home life and childhood encounters with school bullies to an adulthood marked by regrettable decisions driven by fear.

In spite of the very funny situations and one-liners, a parallel narrative emerges. As we witness Daniel’s past fears during his ongoing trial, we also see how fear hinders his new relationship with Julia.

There is a very funny scene where they go to a place called the Past Lives Pavilion; that’s where Julia says the best hot dogs are, after all. Daniel and Julia enter their separate booths and are greeted by none other than Shirley MacLaine (not a character, but the actress herself) before witnessing moments from other incarnations of their lives. Julia is excited and loves the experience. She was Prince Valliant, while Daniel discovers he had been at some point an aboriginal native unsuccessfully running for his life from some wild jungle cat. Suffice it to say, fear has seemingly always been a driving factor in his life, and this remains true even in his afterlife.

…But Fear Itself

Unlike other films by Albert Brooks, Defending Your Life has a strong ending, one that is both satisfying and substantive. It addresses Daniel’s fears as head on as his earlier bus crash. What makes the film great isn’t the romance or even the hilarious observational humor but it’s willingness to grapple with human motives.

Sure, we see signs of Daniel’s worldly success here and there: he was married, his fellow business executives threw him a party and gave him presents, and he mentioned in passing that he had a dog. For his day and time, he had what many would consider to be a happy life. But beyond the BMW and the Perry Ellis suits, Daniel’s life was ruled by fear, and it was something he was required to answer for.

Of course I am not proposing we are reincarnated, or that actual judgment plays a religious role in what could be the next stage of our existence. But it leads us to reflect: if fear can be responsible for a wasted life, then what can we embrace to give meaning to our lives?

And Defending Your Life actually provides the correct answer: Love.

To live a life of love is brave. In a world filled with hate and war, so many of us are left with terrible choices. From how we treat our loved ones, to our neighbors who may be marginalized in some way, love is not always an obvious or easy choice, but it is Christlike.

We don’t see Daniel Miller (a probably Jewish character played by a Jewish actor) chatting with Palestinians, or helping migrants build a new life, nor do we witness him providing shelter for the homeless, feeding the hungry, or simply responding lovingly to people who mistreat him. But we see him accepted and loved by Julia, someone who would have done any and all of those things.

Of course, as Christ-followers, we are called to live lives that are the antidote to the fears of the world. 1 John 4:18 says, “There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear; for fear has to do with punishment, and whoever fears has not reached perfection in love.”

Unfortunately, many in the church (at least in North America) are ruled by fear: fear of politics they don’t agree with; fear of people whose sexuality they don’t understand; fear of others who identify with pronouns that may or may not be binary; fear of those who come from other countries without documentation; fear of others who have different skin colors or languages; fear of loving people.

And that last one is the most important, of course. We cannot authentically offer grace to others as the hands and feet of Jesus if we expect others to change in any way. Unconditional love is just that. And anything else is just a fancy way to fear and judge others.

Maybe we in the church need to learn that before we can move on to whatever lies ahead.

★★★★☆