“That floss is going to give you a fit,” Miss Lou-Ann clucked as she watched me make another attempt to thread my needle. I took up three strands of the gold embroidery floss and tried to roll them into a knot between my thumb and forefinger as she had shown me — only to have the strands fall apart yet again.

It was a cool morning in late April. Rain clouds were gathering outside the window where her two cats dozed, opposite a needlepoint tapestry of scarlet Kentucky cardinals perched in a tree. But the cozy atmosphere belied the seriousness of my visit. I had come to Miss Lou-Ann in hopes of a small miracle: namely, that she could teach me enough about needlework in two-and-a-half hours for me to fulfill the promise I had made to embroider a square of pink cloth with one of Allah’s Divine Names.

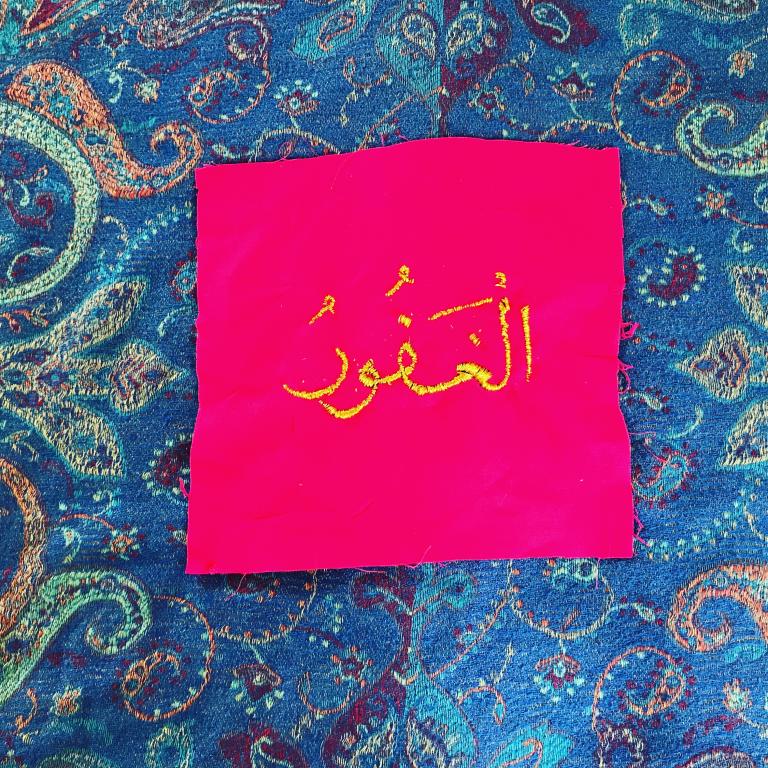

When I had presented Miss Lou-Ann with my project, I had wondered if should I tell her the back story. About the aim of creating a quilt of all 99 Names of God, each square with one Name stitched by our Mevlevli sisters in countries all over the world; about the conversations on retreat in Costa Rica that convinced me to join the project despite not having held a needle and thread since approximately age 8; about the moment in the departure lounge of the Liberia airport when I reached into a friend’s backpack and drew out the square with al-Ghafur, the Most Forgiving, a Name which had touched me but also unsettled me in a way I had not been able to articulate.

My concerns — or perhaps my eagerness to share — turned out to be ill-founded. Miss Lou-Ann was neither taken aback by a word in Arabic lettered in black marker, nor was she particularly interested in what it meant. Instead, she looked at the square of cloth, flipped it over and asked to see the thread I had brought.

“I have to tell you, with this kind of metallic floss, the gold is going to wear off after a couple of stitches. So you’re going to have to rethread your needle and keep starting over again,” she said. Then, peering over her glasses: “Don’t get frustrated.”

She had assessed me correctly as the impatient type. Though as-Sabr wasn’t the Name that came to me on my square, it would clearly be part of the project. Eyvallah, I thought. But why al-Ghafur? Every time I considered the question, I felt a little frisson of alarm.

What did I do wrong?

It is the same heart-skipping sensation that arrives when someone says, “I’d like to talk to you.”

My immediate response is to scan the landscape of our relationship up to that point, searching for missteps or errors. Knowing myself, it would most likely be a moment of heedlessness resulting in some expression of negativity; or possibly a sin of omission – a failure to show up or rise to a challenge.

If this was the Divine saying, “I’d like to talk to you,” then I was guilty of all of the above and no doubt much more.

I recalled the passage in the Mevlevi Wird that says:

“I ask forgiveness of God for all the sins I have committed consciously or accidentally, openly or secretly. I turn to God in repentance for all my errors, those of which I am aware and those of which I am unaware.”

Whenever I recited it, I became uncomfortably aware of all those raw and untrained parts of my nafs that go around making mischief while my public-facing persona, busy on her phone, fails to even look up. In those moments of muhasaba, a sinking feeling would follow the initial spike of alarm: Oh no. My state is even worse than I thought.

Outside Miss Lou-Ann’s window, it had started to rain. She went out to bring in something from the porch, and I returned to the task of threading my needle. Finally — it worked! The knot now holding securely on the obverse of the cloth, I started embroidering the line of the alif with my gold thread.

I had told myself before arriving at my lesson that I would make this work into a twofold zikr: I would meditate on the Name itself and I would repeat la illaha illallah with each stitch. Instead, I found myself thinking about a Hadith. It was one that had always puzzled me.

Abu Huraira reported: The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, said, “By Him in whose hand is my soul, if you did not sin, Allah would replace you with people who would sin and they would seek forgiveness from Allah and he would forgive them.”

This flew in the face of most of my theological assumptions. Even understanding the Divine as the Infinitely Compassionate and Most Merciful, wouldn’t Allah still be disappointed by our mistakes?

Miss Lou-Ann had returned to the living room. “How we doing?”

I showed her my golden alif, which was shaping up to look a bit like a needle itself.

Once more, she flipped the cloth over, this time assessing the strength of my stitches with a few expert tugs. “Good, you got your knots down. Later we can clip some of this excess off,” she said, indicating the wide loops and loose strands that made the gold line go wild and wiry on the other side.

I was relieved to learn the imperfection of my needlework could be corrected. Moving ahead with more confidence, I finished the alif and had made a start on the ghayn by the end of our lesson.

Once back home, I looked up al-Ghafur in Physicians of the Heart: A Sufi View of the Ninety-Nine Names of Allah. The authors group al-Ghafur with al-Ghaffar, at-Tawwab and al-Afuw into the family of Divine forgiveness. They write:

“Both al-Ghaffar and al-Ghafur have this same root meaning of covering over in a healing kind of way. One of the physical-plane variations of the root of these Names refers to covering over the cracks in a leather water skin using the sticky substance that bees use to repair their hives.”

In that sense, the healing power of al-Ghafur lies both in mending a rift and restoring pliability to something that has become rigid or brittle.

I thought back to a moment earlier that day. I was thanking Miss Lou-Ann for our lesson and packing up my things when she said, “I hope you finish your project.” With the kindly touch of a grandmother, she laid her hand on my shoulder and added: “It’s more important to finish it than for it to be perfect.”

I had smiled and said, “Of course,” but did I really believe that? Was I not the same person who used to drop classes in school and abandon projects of my own if I couldn’t be sure I would do well at them?

“In early childhood, or even before, people develop the misconception that they are supposed to be perfect,” write the authors of Physicians of the Heart. “Then when they make a mistake they often feel rage, anger at themselves. By engaging in self-blame, people block themselves from being truly able to make amends. The first step to overcome such confusion may be to recognize that humans are designed to make mistakes in order to learn.” Seen in the context of the infinite Mercy, the authors explain that our capacity for creating separation and suffering actually becomes a way of entering into a relationship with the Divine forgiveness, “by creating a situation that calls for that remedy.”

Now the Hadith about people who sin made sense. If human beings didn’t make mistakes, the Divine would replace us with people who did — because with forgiveness comes greater intimacy with our Sustainer.

And so I could start to see that receiving al-Ghafur as my Name to sew wasn’t a summons to be tried in court for my crimes, but rather an invitation to talk to God and share my struggles. Especially my struggles with this nafs, who can be worse than the most micromanaging executive, with her insistence on flawless execution and doing everything herself.

To oust such damaging leaders, the boards of corporations often offer a “golden parachute”: a bribe of such richness as to make it impossible for the recipient to cling on to their job. In my case, that golden parachute seemed to have taken the form of the gold floss of my embroidery, which I had finally understood as a concrete metaphor for the baraka that was flowing continually, unstintingly, as a radiant outpouring from al-Ghafur.