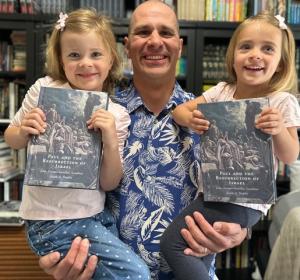

For this episode we will cover a book hot off the press entitled, Paul and the Resurrection of Israel: Jews, Former Gentiles, Israelites (Cambridge University Press, 2024) by Jason A. Staples. This study asks on what basis the gospel that Paul proclaimed provides equal access for both Jews and gentiles. Staples unlocks biblical texts to uncover the importance of Israel’s restoration in Paul’s thinking.

Dr. Staples comes from the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at North Carolina State University, where he is an assistant teaching professor. He has written numerous articles and recently another monograph entitled The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

It is my privilege to converse with Dr. Staples about his new book.

The Interview

Oropeza

What motivated you to write this book?

Staples

This book really goes back to a term paper on the book of Jeremiah back in a 2003 undergraduate survey on the Prophets. One thing that really stood out to me while I was working on that paper was that Jeremiah promises a new/renewed covenant specifically “with the house of Israel and the house of Judah” (Jeremiah 31:31–34). I just couldn’t shake two things that stood out about that passage:

(1) Jeremiah continues to differentiate between “the house of Israel” and “the house of Judah”—and include “the house of Israel” in his expectations of restoration—well over a century after the destruction of the northern kingdom.

(2) The new covenant prophecy is cited in the New Testament as though it included gentiles despite there being no explicit mention of the nations in the passage itself.

Those facts really demand explanation. That’s really what launched this research project, which led first to my book, The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism (2021). This book focused on the first part, and then my current book, Paul and the Resurrection of Israel, attempts to explain the second.

Oropeza

For our readers, “the house of Israel” consisted of the northern tribes of Israel, such as Reuben, Simeon, Ephraim, Manasseh, Gad, Asher, etc. And “the house of Judah” consisted of the southern tribes of Judah and Benjamin foremost. The northern tribes split from the southern tribe during the reign of Rehoboam, King Solomon’s son (see 1 Kings 11–12; 2 Chronicles 10–11).

The northern tribes fell into captivity and were exiled under the might of Assyria. After that, the southern tribes were eventually captured and exiled by Babylon, as described in e. g., 2 Kings, 2 Chronicles, and Jeremiah.

Apart from the Gospels, Paul and the author of Hebrews refer to Jeremiah’s new covenant (1 Corinthians 11:23–26; 2 Cor 3:6–18; Hebrews 8–10; 12:24).

Staples

Explaining how gentiles came to be understood as included in the new covenant promise requires explaining the logic of Paul’s gospel. It argues for gentile incorporation in the fulfillment of the covenantal promises (e.g., Romans 9:8; Galatians 3:14–29).

I realized early in the process that this trajectory required filling a sizable hole in the scholarship in this area. Modern scholars have consistently conflated Israel and Judah while also treating Paul’s emphasis on gentile incorporation as somehow distinct from his expectations for Israel.

Once I started to recognize the centrality of Israel’s restoration to Paul’s gospel and began to understand how he connects that with gentile incorporation in Christ, it became apparent how many otherwise difficult passages suddenly became clearer. The pieces started to snap together.

By that point, it was obvious that this whole paradigm needed to be presented in a robust monograph, which I hope can move scholarship forward. It will help us better understand Paul’s gospel and early Christianity as a whole.

Oropeza

What would you consider to be the top takeaways in your study? In other words, what are perhaps the best insights or contributions to biblical scholarship made in your book?

Staples

This is a more difficult question than it may seem on the surface! I suppose the readers will be the proper judges of this in the long term.

I think one of the most important contributions/takeaways of this book is that it offers a more precise and historically-rooted explanation for who constitutes “ethnic Israel” in Paul’s understanding. Many exegetes of Romans 9–11 frequently refer to Paul’s expectation for the salvation of “ethnic Israel” but with little or no discussion of what that means. This amounts to begging the question, since ethnicity is not a self-evident category.

Here this book builds on my prior book, The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism, which demonstrates that the categories of “Israelite” and “Jew” were not in fact coextensive or synonymous in the first century, as has been nearly universally presumed in modern scholarship. The Samaritans, for example, claim to be Israelites, but—as John 4:9 informs us—they are not Jews.

This is because throughout the Second Temple period (c. 500 BCE—70 CE) “Israel” was understood to be a larger (twelve-tribe) category including but not limited to Jews. Jews were associated with the historical southern kingdom of Judah and the tribes associated with it.

But those from northern Israelite stock—e.g., Reuben, Naphtali, Ephraim, Manasseh—were Israelites without being Jews. Thus, Jews are Israelites but not all Israelites are Jews, and “all Israel” by definition includes non-Jews.

Oropeza

For those who didn’t already know, “all Israel” is the phrase Paul uses in Romans 11:26 to refer to Israel’s salvation and restoration.

Staples

This issue is further complicated by the apparent disappearance of several of the historic tribes of Israel by the first century CE. There is no extant indication of anyone within centuries of that era who identified as a Reubenite or a Gadite or a Naphtalite, for example.

If the promises of God still apply to all twelve tribes of Israel, how exactly will it apply to those tribes of which there is no evidence of survival? This is the sort of question other early Jewish texts like Tobit or 4 Ezra wrestle with.

Those scholars who presume that when Paul says, “and thus all Israel will be saved” (Rom 11:26), he means “all the Jews,” have effectively ruled out Samaritans and any others from northern Israelite stock. This would seem to work against the sort of comprehensive language Paul is using in Romans 9–11. In these chapters he shifts from speaking of “Jews,” as he does throughout the rest of his letters, to discussing “Israel”—thirteen of Paul’s nineteen uses of “Israel” or “Israelite” occur in these three chapters.

As such, I hope that one of the primary contributions of this book is that it forces future interpreters to be more precise and historically and theoretically informed when discussing what Paul means by “Israel.”

Merely tossing the word “ethnic” into the mix doesn’t explain who “Israel” is for Paul. Future interpreters will have to explain how Paul understands the salvation not only of Jews but also of the rest of Israel—and how exactly he defines the boundaries of “Israel” in this context.

Oropeza

The importance of including the northern tribes with “all Israel” becomes even more pointed for those of us who recognize that the “covenant” in Romans 11:27 is echoed from the new covenant in Jeremiah 31.

Staples

Another related contribution is that this book situates Paul firmly within the traditional Jewish eschatology of his own day, presenting a less domesticated Paul than in most scholarship.

Oropeza

Less domesticated? How so?

Staples

On the one hand, much traditional Christian scholarship presents Paul as strikingly at home in the present day, often in contrast with the Judaism of his own day that is presented as representing legalism or racism or some other “regressive” modern sin.

On the other hand, some of the more recent “Paul within Judaism” scholarship has tended to present a similarly domesticated “Jewish Paul.” He is sufficiently weird enough in the right areas to be insulated from a modern audience and generally bracketed from contemporary Jewish concerns.

Some have even proposed that Paul—a first-century Jewish writer—somehow concluded that Israel’s Messiah had come to save only non-Israelites, a remarkably anachronistic reading that serves certain modern concerns well but fits rather poorly in the context of first-century Judaism.

In contrast, my work starts by situating Paul in the context of early Jewish expectations of Israel’s ultimate restoration. These are expectations that E. P. Sanders rightly called synonymous with traditional “Jewish eschatology” as a whole in this period. Remarkably, despite recognizing the importance of such Jewish eschatology in this period and even interpreting Jesus’s ministry through this lens, Sanders himself didn’t read Paul as operating within traditional “Jewish eschatology” but proposed that Paul had departed from it for another thing altogether: “participationist eschatology” (see in Sanders, Jesus and Judaism).

Many since have followed Sanders in treating Paul as though his theology and eschatology were somehow separated from that traditional Jewish eschatological foundation. In my book I propose that Paul is best understood if we read him as operating from within that traditional framework.

In other words, I argue that Paul doesn’t abandon his Jewishness, nor does he repudiate traditional, mainstream Jewish eschatology. Instead, he argues that Jesus has initiated a new phase of that eschatological timetable. And his gospel lays out a specific explanation for how those traditional expectations were being fulfilled in the wake of the crucifixion and resurrection of Israel’s messiah.

My book therefore presents a Paul who looks an awful lot like a traditional apocalyptic first-century Jew, fully coherent in his context. At the same time, the book explains how Paul’s message so substantially reshaped the landscape despite operating within such a traditional framework.

Oropeza

Interesting. So what kind of reshaping does Paul do in your estimation?

Staples

I think the book helps explain Paul’s teaching with respect to the Torah and how that corresponds to the centrality of the spirit throughout his letters, showing how his teaching on Torah corresponds with—and depends on—the restorationist/eschatological aspects of his gospel.

In this respect, I’m especially pleased with the chapter on Romans 10 and Galatians 3. Here is where I argue that Paul does not in fact cite Leviticus 18:5 (“the one who does these things will live by them” cp. Rom 10:5; Gal 3:12) as a works-based foil for his gospel of “salvation by faith” but rather as a proof-text for his gospel itself.

More specifically, the book argues that Paul sees the spirit received by followers of Jesus as the fulfillment of the promises of the Torah and Prophets that God would transform his people into an obedient people. Like many others working within traditional Jewish eschatology, Paul sees this as the first part of the restoration promised to Israel. Thus, ethics and ethical transformation are critical to Paul’s gospel.

Oropeza

It’s good to hear that your book values ethical transformation. I’ll need to reflect more on your interpretation of these passages.

Staples

But if the spirit is promised to Israel and Judah as part of the restoration of the whole twelve-tribe people of Israel, the tricky part is then explaining how and why uncircumcised men are receiving this spirit and what it means. My book aims to uncover Paul’s explanation for that.

In the process, I think this book helps integrate many of the “loose pieces” of the puzzle of Paul’s gospel. It demonstrates that many of the parts of Paul’s message previously thought to be most troublesome—such as Rom 1–2 and Rom 9–11—fit elegantly together with the remainder of his gospel once certain presumptions are abandoned and the whole thing is read starting from a better, more historically rooted, foundation.