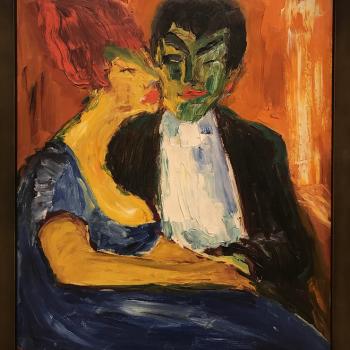

Source: DeviantArt user Grettys

Creative Commons License (on the artist’s page)

Sometimes you walk through a door and realize you don’t belong. Maybe it’s a bar, and everyone stops talking and stares at you. The place hasn’t seen anything but a regular in 15 years. Maybe it’s a retirement party where you’re 35 years younger than the nearest dowager. Or maybe you just tried to join your local Elks only to find a room full of graybeards and wood paneling.

The same logic applies to art. The moon rises just so in the sky (or your wife says she’d like to watch a movie), and you decide you’ll check out The Craft (1996), a teen cult hit beloved by Millennials, especially alt, female Millennials. Page upon page sings its praises. And its ambience and fashion have inspired trend after trend (possibly even innervating the Wachowskis in their breakout trilogy). I am not a witch. I’m an adult. I am not a woman. I am a cis, hetero, white, etc., etc. male. The movie isn’t for me. Getting me to review the movie would be like asking your Greatest Generation grandfather whether Euphoria (2019-Present) eats or not.

For what it’s worth, I actually think it’s a pretty fun film. But, then again, I said I wouldn’t review it. Not like that anyway.

I do, however, find The Craft interesting as a cultural object. It’s got 90s written all over it. The dark-tinged lipsticks, the patent leather, the chokers. Above all, The Craft can’t escape the datedness of its politics, the cultural imaginary whence it came and which it passes on (if implicitly) with every viewing.

Four girlfriends gather together on a beach at night. They invoke the four elements and hold a dagger to each other’s throats, kissing briefly after reciting oaths of allegiance. Each is broken in some way. One comes from an impoverished family, full of physical and potentially sexual abuse. Another is the only Black student at their Catholic high school. A blonde classmate moans that her hair looks like “pubes.” Another is covered in burns. The last, our protagonist, recently arrived in LA and nursing shame over her mother’s death in childbirth, is suicidal. As a friend remarks, she cut herself “the right way,” that is, to die.

The four friends form a “circle” (really more of a square, if you ask me—four corners and all), which brings each of them unfathomable power. Unsurprisingly, they use their magical abilities to right the wrongs done to them. But how do they seek justice? Always and everywhere individually: one has her bully’s hair fall out, another heals her back, another casts a love spell on a boy at school who mistreated her, the last kills her stepfather and invents a massive inheritance for her mother and herself.

Notice that none of these “solutions” solve the fundamental problems plaguing the girls, not in any larger, structural sense. Poverty as such remains untouched (as do its causes; magic proves nothing but a deus ex machina). Standards of beauty go unquestioned. Racism lives to fight another day. What we have here is a failure to imagine a better world. Justice is individual. There is, as Margaret Thatcher remarked, no such thing as society.

Some, however, like the good folks over at the Hit Factory podcast have opined that one character, Nancy (Fairuza Balk), represents a break with this mold. She is a revolutionary. Her extreme poverty, her hatred for everything around her, even her willingness to kill, signal a potential for a broader critique. I’m not so sure. It is true that she, interested in power and elevating herself, becomes cruel and must be magically bound by our protagonist. But does that make her message any better than the supposed conformism around her? Aimless violence, violence with no end but revenge and self-adulation, are not productive, not in the long term. Fanon knew that, and he’s supposed to be some prophet of violent revolution in the Third World.

No, I think The Craft is a product of its time. Its feet sit firmly planted in a world I well remember: the 90s, when history was over, nothing could change, and hard, individualized work—at school, at the office—laid the road to salvation. The Craft questions the salvation offered by 90s America, lashes out at its sterile platitudes. But it can’t escape its individualistic logic. Its magic simply isn’t powerful enough.