Source: Flickr user jean louis mazieres

License: Creative Commons

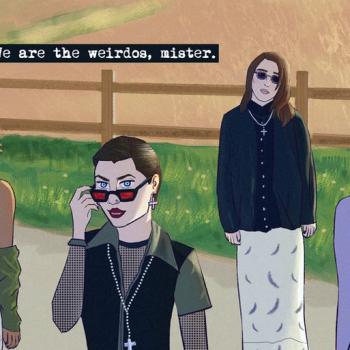

Voyeurism is one of those things. Most of us don’t peep through people’s windows or scan from a park bench looking for rustling in high grass. But the ubiquity of online porn, the way our heads turn at the swirling red lights at the side of the road—most of all the psychic enchantment of movies and TV—suggest an affirmative answer to the killer website’s question in FeardotCom (2002): do you like to watch? Cinema has notoriously furrowed its brow at this conundrum since its early days. From Rear Window (1954) and Peeping Tom (1960) to Angst (1983) and Funny Games (1997), directors have wrestled with what a 101 class might rather boringly call “the ethics of movie-watching.” Whatever they may be, the problem is ineluctable. We’ve all, God help us, got a little Hugh Hefner deep down.

Nowhere has this felt clearer to me than in putting on Hulu’s newest documentary Monster Inside: America’s Most Extreme Haunted House (2023, dir. Andrew Renzi). Stay with me. I know Hulu and Netflix documentaries have a proven record of being bad (and this one is no exception). But a movie about people who like the idea of being pushed to their limits (tortured even), whose experiences at the hands of a sadist have left them traumatized and angry—all relayed through the lens of modern therapy speak—well that was too good to pass up.

That’s the thing: this film deals with McKamey Manor, a “haunted house” run by Russ McKamey, who claims that his “haunt” (that’s what they call them) is the most extreme anywhere. You even get $20,000 if you succeed in traversing the thing. All you have to do is sign a waiver releasing the production from liability should you be mutilated, have your back broken, suffer permanent psychological trauma, get teeth pulled out, die, etc.

Of course, this is nothing like any haunted house most people would go to. It’s a torture chamber. Real or fake, that’s what it enacts or simulates, and it’s this reputation for, let’s say, verisimilitude that has drawn the interest of tens of thousands over a decade and a half. Only those who seek pain beyond pain would even consider such a thing.

For the average movie-watcher, disgusting as it may be, the draw here is the torture, the humiliation, the desire to see and understand how anyone could choose to get waterboarded for their own amusement. Good, old morbid curiosity. It’s Hostel (2005) in real life. If that holds no appeal for you, then you probably won’t put this on anyway. In order for the documentary to work, it has to deliver on the “goods.” That’s the bare minimum, the awful truth.

Monster Inside makes a point not to emphasize the torture itself. There is a great deal of video footage of terrible acts. These were largely, if not all, already publicly available, since Russ constantly taped his victims and used the footage as marketing material (some have even suggested that this documentary is a kind of elaborate hoax to juice his business). But the brief scenes disappear quickly. The interviewees share some other awful experiences flatly and factually. I was locked in a freezer filled up with water. They put a tarantula on me while I was tied down. He waterboarded me. Horrific, but neither emotionally presented nor scintillating—just matter of fact.

So, if the documentary doesn’t trade in the spine chilling, what does it offer? The most banal sort of 2010s and 2020s therapeutic speak. Several scenes involve our “catching” an Iraq vet in a session with a renowned therapist (who later seems to promote self-harm, but that’s another matter). One victim wanted the money; another wanted anything to do with fame. Still another was so obsessed with horror she figured “why not.” A few experts lecture the viewer about understanding and supporting people with strange kinks. We hear about the backstories of a couple victims. The movie implies that these experiences explain their propensity for thrill seeking. Russ McKamey, on their score, went too far. But not all such behavior is too far. We end with a trip to another “extreme haunted house” (torture chamber), one that seems remarkably similar (participants are shot with pellets, tied up, have bags placed over their heads, are degraded, have knives held up to their necks). The differences? There’s a safety word, the acting is far, far hammier, and it ends with your masked assailant giving you a hug and telling you it’s okay to be you.

Right. Russ McKamey seems like a bad man. Certainly, I have no desire to have anything to do with him. I feel bad for these people, because, as a human rights lawyer tells the audience mid-movie, no one deserves to be tortured, and no one can consent to torture. It destroys a person. It’s not to be played around with (she even hints that seeking such behavior out is disrespectful to those who have endured torture at the hands of criminals and states). The film lobs some more specific charges (he may have sexually assaulted someone; his emails show that his kid doesn’t like him; he doesn’t pay his taxes). The first of these is, if true awful, but only obliquely referenced (he is not accused) and the others are immaterial. As far as I can tell, those who participated in the film take issue with McKamey for two reasons:

- He enjoys dominating and torturing people.

- He does not properly observe safe words.

So far as point one is concerned, I can’t imagine anyone who would sign up to run a “fun” torture house if they did not enjoy that kind of thing in a twisted way. I confess point two also left me confused. It’s obviously better if he’s willing to stop when asked. But I find it hard to see how, in a scenario in which extreme harm is the point, this kind of excess can be avoided. Or, put another way: how do you avoid creating or nurturing Russ McKameys in a community whose raison d’être is going further and further and further, observing no limits, and destroying them where they do crop up?

That brings me back to the viewer: what could be more depressing than a movie that invites (in well-established cinematic tradition) voyeurism but that delivers little more than a confused and understandably diatribe against a man who enjoys hurting people? For starters, a movie that turns that into a showcase of people’s horrific brokenness and then tries to solve it in language reminiscent of a corporate wellness seminar. It’s all very sad. Very, very sad. And the worst part?

Nothing to see here, folks. Nothing to see here.