God is creativity.

There’s something intrinsic to how God is conceived in the Bible that pulses with creativity.

In the beginning God created…

In the Hebrew imagination, the creative act of this God takes place first through speech. God, in Genesis 1 is a poet generating worlds. “God says, “Let there be light,” and there is light.

In Genesis 2, we see God crossing artistic genres. In the creation story of Genesis 2, God is not a poet, but a sculptor and gardener, too.

God makes the heavens and the earth, forms the first human from the dust, breathes into the human’s nostrils the breath of life, plants a garden in Eden, and makes fruitful trees grow.

There’s something intrinsically creative in the nature of whatever we mean when we talk about God.

The narrative of God in the Bible continues the theme of creation, except instead of creating a cosmos, the Hebrew Bible’s arc finds God creating a people. What’s more is that the history of the ancient people Israel is a history of the contested struggle between home and exile, between land and landlessness.

The act of God rescuing the Israelites from imperial exile in the prophets is described as a new creation, an act of divine generativity. In the context of God liberating the people from the Babylonians, Isaiah says, “From now on, I will tell you of new things…They are created now, and not long ago.” (Isaiah 48:6-7)

Creation and creativity echoes throughout the Bible.

John’s gospel picks this up the divine-creative theme centuries later: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God, through him all things were made.”

Christ the Word, or in the Hebrew Bible, the Wisdom-Sophia, is present at creation, birthing and making and creating life.

It’s not only God that is creative. The universe is creative. The Big Bang explodes and something that does not exist begins to exist. New possibilities expand.

Here’s how astronomer Adam Frank tells it: “In the beginning, there was a single geometrical point containing all space, time, matter, and energy. This point did not sit in space. It was space. There was no inside and no outside. Then “it” happened. The point exploded and the universe began to expand.” (Quoted in Ilia Delio, The Emergent Christ)

There’s something inherently creative about God, and about the universe, and God and the universe are not separate. You could even say, as Mennonite theologian Gordon Kaufman says, “In the beginning was creativity, and the creativity was with God, and the creativity was God.” (Kaufman In the Beginning…Creativity)

For a religion emerging from creativity, however, Christianity has struggled in its relationship to the arts. On the one hand, the Bible treasures art and is art. The bible is a massive library with every genre you could imagine. There are poems, stories, wisdom sayings and eroticism, science fiction and fantasy.

On the other hand, there is at times within the Hebrew Bible and New Testament a deep skepticism and even violence towards “the other,” including the sacred art, culture, and religion of other non-Israelite peoples.

Much of this skepticism is lumped under the category of what the biblical writers called “idolatry.” The ancient Israelites believed that God could not be represented by images or materials, and that the attempt to do so was itself blasphemous. You must not make a carved image for yourself,” God tells Moses and the ancient Israelites (Exodus 20:4) The prophet Isaiah sneers: “Shall I bow down to a block of wood?” (Isaiah 44:19)

The religious history of Christianity reflects the same tension: an embrace of the arts on the one hand, and skepticism or rejection of the arts on the other.

Specifically, when Christianity meets imperial power, as it so often does in its history, this cross-cultural encounter becomes disastrous. A South African theologian of aesthetics tells that “when Christianity became the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, the bishops of Rome insisted on the destruction of pagan works of art on the grounds that they were idolatrous.” (John W. de Gruchy Christianity, Art, and Transformation)

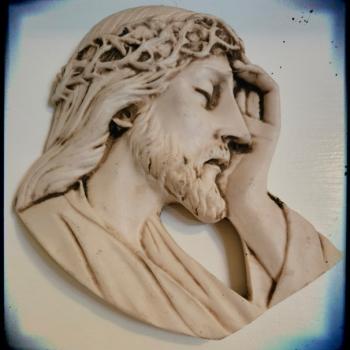

This struggle plays out in the way that sacred art and images are used within the Christian faith itself. Eastern Orthodox believers for centuries have seen images as revealing the presence of God. They call them icons. Jesus is the “image” or icon of the invisible God, according to Colossians 1. Orthodox Christians include as part of their worship painted pictures of Jesus, stories from the gospels, and saints of the church. Protestants, on the other hand, became notorious for their opposition to images in church.

There’s even a radical strain of iconoclastic Lutherans that saw it as their responsibility to tear down stained glass windows and paintings in churches. According to Erasmus, one riot in Basel in 1529 led by these Protestants, resulted in art thrown in a fire, statues torn down, and frescoes coated over. (Erasmus, Epistle MXLVIII to Bilibald).

One way that this tension between embracing and opposing the arts evolves is through the false category of the sacred and secular. On the one hand, there’s sacred art dealing with Christian themes, painters that paint the Madonna and child, and on the other hand, there’s secular art that takes on other themes.

The Counter-Reformation’s Council of Trent in 1563 responded to the Protestant critique of images. They said it’s ok for Catholics to have images of Christ and the Virgin Mary, but they firmly set a boundary around what types of images were acceptable and were not.

They did not support art for art’s sake, but rather, art which aligned with their theological and ecclesiastical, ideological position. De Gruchy sums up their position: “No image shall be set up which is suggestive of false doctrine.”

The line from sacred and secular division leads to fundamentalism. I attended a fundamentalist school in Germany for children of missionaries. At this school, you could not watch movies or music that was “secular” unless it had been approved by an administrative board. So, if a movie or song talked about Jesus, sang about Jesus in the chorus, it was fine. But if it contained non-religious content, it had to be submitted for “approval.” My secret mission was always to see how many unknown and independent music groups I could submit for administrative approval. (I was moderately successful at this.)

Incarnation is the branch of theology that tries to make sense of what it might mean that Jesus the Son of God is also the Son of Man. He’s divine on the one hand, the early theologians say, but he’s human on the other.

If God is creativity, or if creativity is somehow inherent to God, and if this creative God has incarnated divine self in human, material life through Jesus in some way, then human and material life is divine. All of life is sacred.

If God is manifest in our material, human reality, then that means that God is manifest and revealed in all of the arts. And not just the Christian arts. And not just the so-called beautiful or classic works of art, either.

In Jesus’ incarnation, life, death, and resurrection, God is revealed through all of human experience, which means that God is not only present in the typically beautiful or pretty things.

Or, rather, maybe God’s beauty contains the tragedy and the pain. Karl Barth says, “God’s beauty embraces death as well as life, fear as well as joy, what we might call ugly as well as what we might call the beautiful.”

All of the arts, and ultimately all of reality, is an invitation to encounter God’s presence in the death, life, fear, joy, ugliness, and beauty of our own lives and world.

Photos by Barry Bibbs and RhondaK Native Florida Folk Artist on Unsplash