On Friday, the Supreme Court of the United States made a historical ruling that will have drastic effects on the lives of homeless Americans. In Grants Pass v. Oregon, the Supreme Court gave the green light for cities to outlaw and punish homelessness, so long as cities frame it as “camping” in public places.

As Christians, this decision demands a strong, faithful response. For if there is anything positive that Christianity has had to offer the world of political thought, it is this maxim: you can tell a lot about a society by how it treats its poor.

Background to Grants Pass

To understand Grants Pass v. Oregon, we need to understand a few things. The first thing we must consider is a case that preceded it. This case was Martin v. Boise.

I. Martin v. Boise

Martin v. Boise (2018), like Grants Pass, was about homelessness. The question that the justices of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit considered in Martin was whether criminalizing “camping” in public was cruel and unusual. Students of the U.S. Constitution will recall that cruel and unusual punishment is forbidden in the Eighth Amendment.

The justices in Martin ruled that criminalizing “camping” is unconstitutional under a certain condition. It is unconstitutional whenever the number of “campers” exceeds the number of available shelter beds deemed “practically available.” This seems fair, doesn’t it? After all, where else will people sleep if all the shelter beds, practically speaking, are unavailable?

II. The Laws of Grants Pass

Here, we return to the city of Grants Pass. The city had an ordinance which outlawed public camping. According to this ordinance, the first time that anyone was found camping in a public space, like in front of a business, or spending the night camped out in a park, they would be fined.

Sara Rankin, law professor at Seattle University and director of the Homeless Rights Advocacy Project, points out that fines make a difficult life even harder for people on the streets. She writes,

When you fine someone who can’t pay, the fine can eventually turn into a misdemeanor. Studies have shown that it doesn’t help an already poor person to be driven into debt. Fining someone makes them less likely to emerge from homelessness, including by ruining their credit score and making them unable to afford basic needs like food.

After “breaking” the public camping law multiple times, a person may become incarcerated. For someone who is already unlikely to successfully apply for housing or jobs, incarceration becomes a blot on one’s record.

III. The Case Begins

A class action was filed against Grants Pass on the grounds that its ordinance constituted cruel and unusual punishment. Using the legal reasoning of Martin, the plaintiffs in the class action claimed that the people on the streets exceeded the number of available beds in the city shelter in Grants Pass.

The U.S. Supreme Court justices note that this claim was partly made because of the nature of this city shelter. To stay in this shelter, folks must attend its religious services and abstain from smoking. Requiring religiosity is something quite common among Christian homeless ministries and shelters.

The Ninth Circuit, which ruled on Martin in the first place, upheld Martin. However, the city of Grants Pass did not acquiesce. It appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Grants Pass was not alone. Other counties, cities, and even whole states asked the Supreme Court to review Martin. It was clear that Martin‘s protection of homeless Americans was unpopular for people in power.

Ruling Against the Homeless

When the Supreme Court justices took on the case, they ultimately ruled against homeless Americans. These Americans’ protections under the Ninth Circuit vanished. But why?

I. The Make-Up of the Supreme Court

One thing we must understand is that the U.S. Supreme Court justices are where they are due to what is called “stacking the court.” There are only nine justices in the Supreme Court. To win a case, five justices must rule in favor of a decision. Though justices are supposed to be politically neutral, judges will be appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of either the Republicans or the Democrats.

As things stand today, one third of the Court is a creation of former president Donald Trump. Three of the nine justices were nominated by Trump and confirmed by the Republican-majority Senate in the span of only four years. (These justices are Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.)

Stacking the Court, though it goes against the founders’ intent for the judicial system, can manipulate the Court for political gain. If one’s party has a majority on the Court, any cases that the Court decides on will be advantageous to that party. As things stand today, the U.S. Supreme Court leans heavily to the Right.

II. Originalism and the Eighth Amendment

Since these justices were all appointed by Trump, they share a common hermeneutic in how they read the Constitution. Conservative justices often prefer what is called constitutional originalism. Simply put, to ascertain the true or worthwhile meaning of the Constitution, one must interpret it as it was originally meant.

Since the Supreme Court was adjudicating whether laws like Grant Pass’s public camping ordinance violated the Eighth Amendment, they interpreted the Eighth Amendment according to this theory of interpretation. They took the words “cruel and unusual” to mean what they originally meant. According to the majority opinion, a punishment was cruel if it caused “pain,” “terror,” or “disgrace.” A punishment was unusual if it was no longer commonly used.

The majority sums up their decision like this.

[Grants Pass] imposes only limited fines for first-time offenders, an order temporarily barring an individual from camping in a public park for repeat offenders, and a maximum sentence of 30 days in jail for those who later violate an order. Such punishments do not qualify as cruel because they are not designed to “superad[d]” “terror, pain, or disgrace.” Nor are they unusual, because similarly limited fines and jail terms have been and remain among “the usual mode[s]” for punishing criminal offenses throughout the country. Indeed, cities and States across the country have long employed similar punishments for similar offenses. (City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, 603 U.S. ___ (2024). Internal citations omitted.)

III. The Alternative Reading

It seems that the claim that Grant Pass’s ordinance was cruel and unusual is based on a different interpretation of the Constitution. It is an interpretation that does not prioritize what the Constitution originally meant.

For the class action in Grant Pass, “cruelty” is more broadly defined. The very thought of punishing human beings for camping out in public, having nowhere else to go, is cruel. To put it more philosophically, it is absurd. It is like making in-person grocery shopping illegal, then punishing people for getting groceries in-person because they are unable to order groceries online.

The majority in Grants Pass sidestep this absurdity by distinguishing between status and action. They are not ruling against the status of being homeless. No, they are ruling against the act of camping out in public. But given the context of the case, this is a distinction without difference. It is in the nature of the homeless experience to have to camp out in public. If there are no practically available shelter beds, where else is one to lay one’s head to rest?

Condemning the Grants Pass Decision

As Christians, we must address this ruling. It must be scrutinized under the highest laws of creation, laws that are higher than America’s laws of the land. And the laws of Christianity certainly have something to say about the justices’ lack of concern for America’s poor.

I. Poverty in the Roman Empire

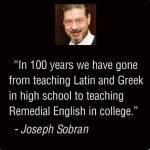

Peter Brown, an Irish historian, writes about how poverty was construed in the Greco-Roman order prior to Christianity. Poverty was an unfortunate reality. But poverty became an opportunity for the wealthy to alleviate themselves, comfortably, of their excess riches.

Giving to the poor became a way of showing that one had more than what one needed. It also legitimated the fact that rich people possessed that extra wealth. This way of viewing poverty removed all agency from the poor, and rendered them as objects of generosity. It placed all the agency on the wealthy, and in exercising this agency rightly, the wealthy were praised for their wealth.

II. Poverty in Christianity

Then, Christianity came onto the scene. Rather than praising the wealthy for helping their fellow human beings with their left over cents, Christians challenged the very terms of this Greco-Roman game. Yes, the wealthy give to the poor, but does this make them praiseworthy?

As Brown argues, Christianity by late antiquity had changed the game. Christians had brought a new understanding of economic and political legitimacy.

As Luke Bretherton puts it in Christ and the Common Life, “From this period onward, in European Christian contexts, concern for the poor marked whether a political order was legitimate” (p. 73). Later on, Bretherton writes, “Treatment of the poor is a diagnostic of whether power and privilege are exercised justly and lovingly. . . . By seeing our common life from the perspective of the poor, what is unveiled is who counts and what is valued” (p. 77).

Seeing from the Perspective of the Homeless

If we look at Grants Pass through the eyes of the poor, what do we see? Do we see an absence of cruelty? Or do we see an abundance of it?

To maintain our distinctiveness as Christians, we must not sacrifice our historical focus on the poor. For decisions such as these affect the poor most heavily.

Indeed, it is from a Christian perspective that the punishments meted out by Grants Pass are revealed to be cruel and unusual. They are cruel, because they are absurd and merciless. And they are unusual, because one would never find a law like that in God’s Kingdom.

If we can tell a lot about a society by how it treats its poor, what can we tell about America today? And in light of this, how can we as Christians work to bring this nation and our neighbors to see the error in their ways?

See my prior article, “Would Jesus Make Fun of Homeless People?” for more theo-political reflection on how we talk about homelessness in today’s society.