One of my first public posts ever declared my first experiences of reading literature from Latin America especially from my father’s country Costa Rica. Sometimes I think about why I am constantly writing about literature. It seems every other essay I write I am advocating about reading fiction. Perhaps this because as someone tasked with teaching history, I have to convince myself that it is okay to escape to the world of fiction. Still, and it is not the point of this essay, I do think the great works of literature are necessary for teaching history, especially when they are culturally significant. It really was some of the best books from Latin America that opened up its history for me.

But what if I wanted to look and the door to this literary world was closed? The only way I could really read the few works from Costa Rica was because of the hard work by translators. I think I only had this realization about translation because of the experiential connection between these books and my own family ties. Books written about Costa Rica in English are relatively few (good luck searching for one at the local B&N-perhaps in the travel section?). I did not really have this literary awareness until recently. For instance, years ago I was obsessed about reading all the major works of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. I did not, however, really reflect on the miracle of translation that made these large books available. I just knew that these were classics, I could find them at any book store, and most importantly, I enjoyed reading them.

Well why not just read the books in Spanish? First, if you think it is difficult finding a translated book, imagine looking for the Spanish version at a bookstore in the U.S. Second, reading in Spanish is not as easy as it sounds especially if coming to a second language later in life. In fact, my cousin left me volumes of Costa Rican works that are in Spanish, but it takes a lot of patience to read even a single page. One of the greatest challenges is that language shifts and evolves so it is not as easy as picking up the basic tools of a language in the present then trying to read a book from Costa Rica published around WWII. Again, that is why translations, including updated translated works, are so important.

I have written earlier about Mark Noll’s book about the reception of C.S. Lewis’s works here in the United States around the war years (late 1930s to late 1940s). I recently wrapped up a review of this book for The Lamp-Post. One of the questions I probed was Lewis’s reception was about the same time period when an explosion of global literature was provided to American readers because of the hard work of translators (at least that is my hunch). Even just a cursory view of new books illustrates that more and more books are being made available to readers from across the world because of translators (again, just browse the front of a B&N). This is great news, but are there potential signs of future problems?

What if there is a decrease in language studies? Does this mean translation is in trouble? A recent article describes some of the potential problems of the decrease in language majors but also a hopeful sign I find particularly encouraging. Less young people are focusing on learning a foreign language as a career path. Since this conversation is also connected to the historical events around 2020 it may be a while before we totally comprehend what this trend means in the long run. The article does point to what I find an encouraging phenomenon: Korean course enrollments are on the rise. It seems that the cultural focus on Korean entertainment (music and TV shows) has sparked an interest.

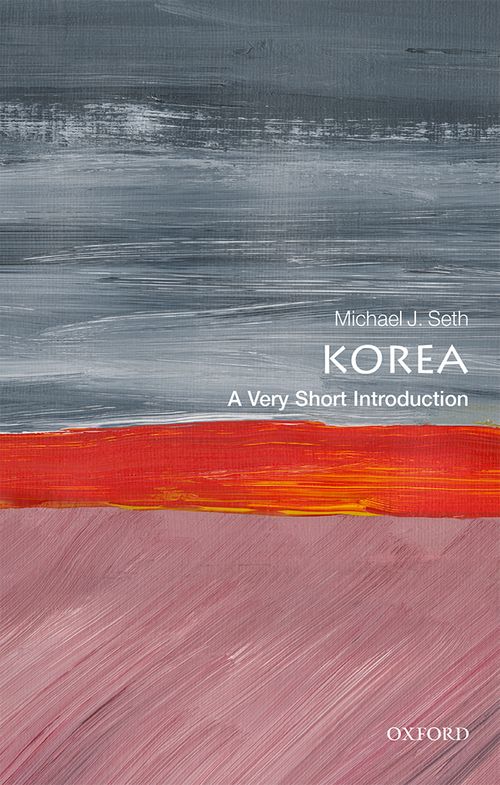

This shift because of cultural interest gives me a lot of hope and I think it is something we have to all adapt to. For instance, this is not only a cultural trend by people who like harmonious, dancing bands or apocalyptical game shows, but even Oxford has recently taken notice.

You know you have arrived when you have one of these little books dedicated to you. Moreover, contemporary Korean literature is fantastic. For example, I have found the work of Han Kang and Bae Suah particularly engrossing.

Of course, I will take this trend as a reminder of the importance of global literature. We take for granted that the fact that more and more of it is readily available. I am saying this because translation work is very difficult and time consuming. To make matters worse, oftentimes the translator gets little credit for their work (sometimes their name does not even appear on the book cover).

One of the reasons for the subtraction of language studies is the growth of translation tools (often found on your phone). There is no reason to decry the handy tools technology has given us to make understanding a foreign language easier for practical use (especially when you took the wrong train to get to the airport in Tokyo and missed the transfer-much thanks to Google translator and the help we received at the stations because of it). Still, a practical tool will never replace the hard work of learning another language but also the lifetime joy of being able to communicate. I realized, however, a very long time ago that I am not very good at languages (it might be a problem of patience), but I keep trying.

Translations are a work of patience. Oftentimes certain translators become experts of particular writers. There is a relationship of trust that is built. These things take a lot of time, and in fact, a great dedication not just to the work being translated but also the cultural history of the book and its author. The process of translation often begins when the translator reads a book and wants to share it literally with the world.

I commute almost daily to work. One of the things that helps pass the time is listening to literary podcasts. Some of my favorite episodes is when the host interviews a translator. Every now and then one gets the opportunity to hear from an expert. For example, the literary podcast Beyond the Zero recently interviewed Natasha Wimmer, who translates many Spanish language classics including the work of Roberto Bolaño.

In some ways, following the legacy of Latin American Boom writers like Márquez, Cortázar, Vargas Llosa, Allende, and Fuentes, the hard work of translation of Latin American authors by Wimmer and others has led to the increase in translated works into English. Some say this original Boom (not too long after Lewis’s reception in the U.S.) has been continual (also don’t forget Borges’s shining star) and even literary works from places like Costa Rica will pop up every now and then.

Whether we are approaching the history course or picking the next novel to read before bed, we should say a little prayer of thanks for the hard work of translators, those often unsung literary heroes, who have spent so much time just to grant us a little narrative beauty.