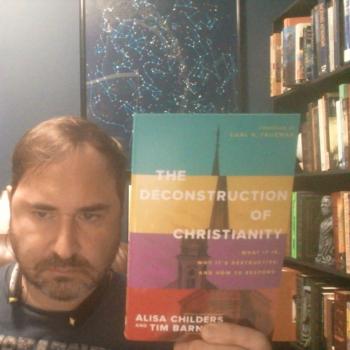

As a deconversion researcher, it is becoming ever more apparent that culture and time period have a heavy influence on the form deconversion tends to take. In my review of the book You Lost Me, I demonstrated how the researcher had captured a time when millennials were the young adults of the world, and how the culture at the time influenced the reasons and ways they left religion. In my review of the more recent book Deconstruction of Christianity, I looked at that same phenomenon from the perspective a decade later, and showed the differences that deconversion tended to take.

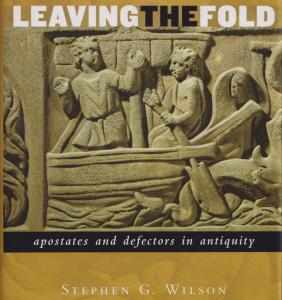

The book Leaving the Fold: Apostates and Defectors in Antiquity looks at the surviving records of the ancient world – from the third century C.E. to the third century B.C.E. – and examines the phenomenon of deconversion in these ancient times and cultures.

The book is divided into four sections: deconversions in the Jewish world of antiquity, deconversions in the early Christian church, deconversions in the pagan world (here, “pagan” refers to the Hellenistic cultures during the Roman Empire), and a brief overview of current research on deconversion. This book was published in 2004, so “current” research refers to deconversion research in the 1990s which, again, was a time capsule of its own.

Jewish Apostates

To examine the phenomenon of Jewish apostacy, it is worth noting how Judaism differs from any other world religion. That is, Judaism is both an ethnic or national identity as well as a system of religious belief and practice. This makes apostacy from Judaism somewhat complicated. For instance, it is possible – if rare- for a person who was not born into the Jewish culture to convert to Judaism. But is that person adopting the ethnic or the religious identity? Since the two are so closely related, generally the person is adopting both (this kind of conversion is most frequently a result of marrying into the culture, since technically Jewish law forbids Jews to marry non-Jews). When a Jew leaves the practice of Judaism, they are both a Jew in the sense that they were born from Jews, and a non-Jew in the sense that they have denied their religious practice and cultural heritage.

Prior to the rise of Christianity, Jewish apostates did not appear to exit Judaism in order to join an alternative religion, except when social forces placed them under pressure to do so. Rather, they seem to exit practicing Judaism entirely to become irreligious. This is not to say that they became Atheists. There isn’t enough evidence to say where they landed in the theological sense, although they do seem to frequently take a hostile relationship with the Jewish religious institution. But this may have more to do with the power it held or its opposition to the dominant culture.

At any rate, their reasons for defecting do have striking similarities to modern instances of deconversion:

- rebellion against traditional values in deference to the more novel Hellenistic values

- aversion to the exclusivism of Jewish ideology

- the perception of religious leaders abusing their power

- Identifying moral objections to or contradictions in the Torah

One reason they may not have ended up as Atheists is because this was not a cultural option at the time – as opposed to 21st century Western culture wherein Atheism is a live option for anyone who chooses to adopt it.

In the period prior to Christianity, Jews would sometimes leave Judaism to join the more novel philosophical schools of Greek and Roman culture. In these instances, they were not necessarily transferring their allegiance to the rulers of those nations, or even necessarily the pagan gods. Rather, they were adopting the practices and philosophies associated with schools such as Platonism, Epicureanism, Stoicism, and so forth. Since these philosophies tended to involve moral beliefs and practices such as dietary and sexual ethics, the Jews were not entirely discarding their Jewish identity, they were simply “tinkering” with other practices and beliefs.

Christian Apostates

In order to study apostacy, the author of this book, a historian named Stephen G. Wilson, had to struggle with the definition of “apostacy.” In his discussion on the subject, Wilson examines three different kinds of apostacy. The first is the adoption of novel beliefs and practices related to the existing religion – as when Gnosticism began to creep into the early church, or when early Christians differed on the nature of Christ with respect to divinity. If a Christian was firmly in support of one sect, but then migrated to another, the author examines this under the label of “apostacy.”

The second kind of apostacy examined by the author would be a migration back to the previous beliefs and practices the person had before converting to Christianity. A very recent study examined a similar process in Asia, wherein Christian converts felt cultural pressure to return to practicing Buddhism. In this study, their desire to return to Buddhism had to do with the comforting familiarity of their former religious practices, as well as the way in which returning to Buddhism would make life easier in relationship to blending with their culture and facilitating comfortable relationships with their family. It was not the truth or falsity of Buddhism or Christianity under consideration, but rather the convenience.

A similar process can be seen in early Christian converts, whose life would be much easier if they were to return to the practices of the larger culture. Which leads us to the next subject.

Forced Deconversion

Much ink was spilled by Roman historians about the brutal techniques by which Christians were forced to deny their Christian beliefs. The options tended to boil down to either deny one’s Christianity or die. Under such duress it is understandable how many Christians would leave Christianity – not because of cultural pressures, not because of doubts, but for the simple desire for self-preservation. Christians subject to these threats would tend to go one of four ways. Sometimes they would do the noble thing and simply refuse to concede their faith, at which point they suffered the consequences of their fidelity. Sometimes they would give in to the threats and leave Christianity entirely. Sometimes they would outwardly leave in order to preserve their lives, property, and family, while still secretly practicing the faith. And sometimes they would migrate to practicing Judaism instead. Judaism was a protected religion under Roman law, which would protect the person from Roman threats, and Jewish practices were not entirely in contradiction to Christianity. This allowed them to maintain some semblance of worshiping the God of the Bible under slightly different means.

Pagan Deconversions

The section of the book which examined deconversion from various pagan schools of thought and practice seemed a great deal more political, with divisions and in-fighting being the apparent drivers of much religious exit. Because the author included leaving one religion for another as part of his definition of deconversion, the rise of Christianity had some impact on the pagan practitioners as many were attracted to this new religious order over others.

Ancient Deconversion Versus Modern Deconversion

One distinct feature which separates the ancient world from the modern world was the absolute ubiquity of religion. While there were no doubt people in antiquity who swore allegiance to no particular god or institution, such a life would be very isolated, since to participate in society at all was to be part of some kind of religion.

By contrast, the modern Western world offers people the freedom to be free to navigate life and society, to make friends, participate in groups, and pursue one’s personal interests, with no religious affiliation whatsoever. In the ancient world, to deconvert was almost always to transition one’s loyalty from one religious or philosophical school to another.

It has been argued that humans are fundamentally religious, and that even when a person is an atheist or a “none,” that person will find something else to replace religious devotion, such as intense political involvement or devoted participation in one of the multitude of fandoms offered by the modern world. I do not personally have the research to accept or deny this claim, but whatever the case, modern people are not as beholden to religion as such. Because of this, a modern deconvert can comfortably migrate to a non-religious category such as being an “none,” or an irreligious category such as “atheism,” categories which simply did not exist in the ancient world.

The author of the book does make one observation about ancient apostacy which seems just as true today as it did then:

“It is not unusual for certain types of defectors – those who become active opponents of the group they have abandoned – to exaggerate the shortcomings of the community they have left, and give everything a negative twist. It would also not be unknown for them to attribute their defection to grand motives when the reality may have been more mundane.”

This is true of human nature in general. Whenever a conflict arises, each individual within the conflict will exaggerate the error of the other party, if by exaggeration, that person makes him or herself look to be the hero of the tale. It would be fallacious to believe that this is always done in terms of deception or malice. People simply desire to be in the right, and their minds will frequently provide them the excuse to do so.

In the modern world, when an individual is cast in competition with an institution – as with an individual versus a church, it is the instinct of the modern person to assume that the institution is always in the wrong and the individual is always in the right. This certainly cannot be true in every case, but nevertheless, we tend to side with the underdog instinctually.

The fact that people tend to cast their allegiances with the popular culture when culture is in conflict with religion appears to be a constant theme across the ages. Young Jews would exit Jewish religion and integrate with the Greek culture. This serves as a good analog to the modern day. In ancient times, people were rarely raised in the Christian church, but rather converted to Christianity. This was due to the fact that Christianity was a small and very new religion at the time. Consequently, we do not have as much evidence of people leaving Christianity to join the popular culture. Frequently it was the opposite case.

However, because Jews were raised in Judaism, the temptation to leave the religion of their youth to join the popular culture of the Greeks was a frequent story. As Western culture secularizes, and the influence of Christianity rapidly declines, we see each new generation exiting the church in waves, as they decide to adopt popular culture over their religious upbringing.

Another common feature seen especially in Christian deconversion in antiquity is that prosperity tends to breed indifference. That is to say, the people most attracted to early Christianity were the poor and the destitute. Wealthy people were much more rarely attracted to this new religion. And for those within Christianity, as their wealth increased, so did their likelihood of leaving the church.

The same can be seen in modern day. Wealthier nations are distinctly less religious than poorer nations. Wealthier people are less likely to be religious. And as the prosperity of a region increases, the religiosity of that region declines. One can overlay a map of wealth and a map of religious practice, and see the distinct correlation.

Why is this? Some suggest that wealth offers better education, and when people are better educated, they leave their silly superstitious notions. However, this does not explain why this phenomenon occurred in the ancient world, given that superstition was ubiquitous and science as such did not exist.

More likely the explanation is that access to wealth offers access to alternative forms of fulfillment. When one is poor, one’s only access to community, to education, to child support, and to the necessities of life lay in communities which provide these things out of charity and loyalty to one another. As one becomes more affluent, one can purchase one’s way into elite communities which offer power and personal advancement in addition to community.

The Book

The work of Stephen G. Wilson offers a fascinating look into an age-old phenomenon which helps to cast light on the modern form of deconversion by exploring its ancient correlate. Wilson’s writing is easy to read, and his scholarly work is of highest quality. The book is a rather quick read at just over a hundred pages (not including notes and references), and the information the book provides will never go out of date. For those interested in the subject (as I am), I would highly recommend this book.